Related Research Articles

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of mental processes such as attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, creativity, and reasoning. Cognitive psychology originated in the 1960s in a break from behaviorism, which held from the 1920s to 1950s that unobservable mental processes were outside the realm of empirical science. This break came as researchers in linguistics and cybernetics, as well as applied psychology, used models of mental processing to explain human behavior. Work derived from cognitive psychology was integrated into other branches of psychology and various other modern disciplines like cognitive science, linguistics, and economics. The domain of cognitive psychology overlaps with that of cognitive science, which takes a more interdisciplinary approach and includes studies of non-human subjects and artificial intelligence.

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of how and why humans grow, change, and adapt across the course of their lives. Originally concerned with infants and children, the field has expanded to include adolescence, adult development, aging, and the entire lifespan. Developmental psychologists aim to explain how thinking, feeling, and behaviors change throughout life. This field examines change across three major dimensions, which are physical development, cognitive development, and social emotional development. Within these three dimensions are a broad range of topics including motor skills, executive functions, moral understanding, language acquisition, social change, personality, emotional development, self-concept, and identity formation.

Jean William Fritz Piaget was a Swiss psychologist known for his work on child development. Piaget's theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called genetic epistemology.

Piaget's theory of cognitive development, or his genetic epistemology, is a comprehensive theory about the nature and development of human intelligence. It was originated by the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). The theory deals with the nature of knowledge itself and how humans gradually come to acquire, construct, and use it. Piaget's theory is mainly known as a developmental stage theory.

Cognitive development is a field of study in neuroscience and psychology focusing on a child's development in terms of information processing, conceptual resources, perceptual skill, language learning, and other aspects of the developed adult brain and cognitive psychology. Qualitative differences between how a child processes their waking experience and how an adult processes their waking experience are acknowledged. Cognitive development is defined as the emergence of the ability to consciously cognize, understand, and articulate their understanding in adult terms. Cognitive development is how a person perceives, thinks, and gains understanding of their world through the relations of genetic and learning factors. There are four stages to cognitive information development. They are, reasoning, intelligence, language, and memory. These stages start when the baby is about 18 months old, they play with toys, listen to their parents speak, they watch TV, anything that catches their attention helps build their cognitive development.

Egocentrism refers to difficulty differentiating between self and other. More specifically, it is difficulty in accurately perceiving and understanding perspectives other than one's own. Egocentrism is found across the life span: in infancy, early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Although egocentric behaviors are less prominent in adulthood, the existence of some forms of egocentrism in adulthood indicates that overcoming egocentrism may be a lifelong development that never achieves completion. Adults appear to be less egocentric than children because they are faster to correct from an initially egocentric perspective than children, not because they are less likely to initially adopt an egocentric perspective.

Conservation refers to a logical thinking ability that allows a person to determine that a certain quantity will remain the same despite adjustment of the container, shape, or apparent size, according to the psychologist Jean Piaget. His theory posits that this ability is not present in children during the preoperational stage of their development at ages 2–7 but develops in the concrete operational stage from ages 7–11.

The A-not-B error is an incomplete or absent schema of object permanence, normally observed during the sensorimotor stage of Jean Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development.

The imaginary audience refers to a psychological state where an individual imagines and believes that multitudes of people are listening to or watching them. It is one of the mental constructs in David Elkind's idea of adolescent egocentrism. Though the term refers to an experience exhibited in young adolescence as part of development, people of any age may harbor a fantasy of an imaginary audience.

The model of hierarchical complexity (MHC) is a framework for scoring how complex a behavior is, such as verbal reasoning or other cognitive tasks. It quantifies the order of hierarchical complexity of a task based on mathematical principles of how the information is organized, in terms of information science. This model was developed by Michael Commons and Francis Richards in the early 1980s.

According to Alberts, Elkind, and Ginsberg the personal fable "is the corollary to the imaginary audience. Thinking of themselves as the center of attention, the adolescent comes to believe that it is because they are special and unique.” It is found during the formal operational stage in Piagetian theory, along with the imaginary audience. Feelings of invulnerability are also common. The term "personal fable" was first coined by the psychologist David Elkind in his 1967 work Egocentrism in Adolescence.

Domain-general learning theories of development suggest that humans are born with mechanisms in the brain that exist to support and guide learning on a broad level, regardless of the type of information being learned. Domain-general learning theories also recognize that although learning different types of new information may be processed in the same way and in the same areas of the brain, different domains also function interdependently. Because these generalized domains work together, skills developed from one learned activity may translate into benefits with skills not yet learned. Another facet of domain-general learning theories is that knowledge within domains is cumulative, and builds under these domains over time to contribute to our greater knowledge structure. Psychologists whose theories align with domain-general framework include developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, who theorized that people develop a global knowledge structure which contains cohesive, whole knowledge internalized from experience, and psychologist Charles Spearman, whose work led to a theory on the existence of a single factor accounting for all general cognitive ability.

Infant cognitive development is the first stage of human cognitive development, in the youngest children. The academic field of infant cognitive development studies of how psychological processes involved in thinking and knowing develop in young children. Information is acquired in a number of ways including through sight, sound, touch, taste, smell and language, all of which require processing by our cognitive system. However, cognition begins through social bonds between children and caregivers, which gradually increase through the essential motive force of Shared intentionality. The notion of Shared intentionality describes unaware processes during social learning at the onset of life when organisms in the simple reflexes substage of the sensorimotor stage of cognitive development do not maintain communication via the sensory system.

Bärbel Elisabeth Inhelder (15 April 1913 – 17 February 1997) was a Swiss psychologist most known for her work under psychologist and epistemologist Jean Piaget and their contributions toward child development.

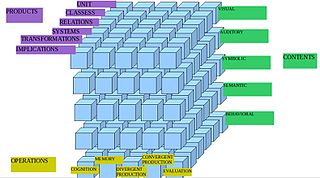

Mental operations are operations that affect mental contents. Initially, operations of reasoning have been the object of logic alone. Pierre Janet was one of the first to use the concept in psychology. Mental operations have been investigated at a developmental level by Jean Piaget, and from a psychometric perspective by J. P. Guilford. There is also a cognitive approach to the subject, as well as a systems view of it.

The water-level task is an experiment in developmental and cognitive psychology developed by Jean Piaget. The experiment attempts to assess the subject's reasoning ability in spatial relations. To do so the subject is shown pictures depicting various shaped bottles with a water level marked, then shown pictures of the bottles tilted on different angles without the level marked, and the subject is asked to mark where the water level would be.

Role-taking theory is the social-psychological concept that one of the most important factors in facilitating social cognition in children is the growing ability to understand others’ feelings and perspectives, an ability that emerges as a result of general cognitive growth. Part of this process requires that children come to realize that others’ views may differ from their own. Role-taking ability involves understanding the cognitive and affective aspects of another person's point of view, and differs from perceptual perspective taking, which is the ability to recognize another person's visual point of view of the environment. Furthermore, albeit some mixed evidence on the issue, role taking and perceptual perspective taking seem to be functionally and developmentally independent of each other.

Horizontal and vertical décalage are terms coined by developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, which he used to describe the four stages in Piaget's theory of cognitive development: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operations, and formal operations. According to Piaget, horizontal and vertical décalage generally occur during the concrete operations stage of development.

Adolescent egocentrism is a term that child psychologist David Elkind used to describe the phenomenon of adolescents' inability to distinguish between their perception of what others think about them and what people actually think in reality. Elkind's theory on adolescent egocentrism is drawn from Piaget's theory on cognitive developmental stages, which argues that formal operations enable adolescents to construct imaginary situations and abstract thinking.

The Three Mountains Task was a task developed by Jean Piaget, a developmental psychologist from Switzerland. Piaget came up with a theory for developmental psychology based on cognitive development. Cognitive development, according to his theory, took place in four stages. These four stages were classified as the sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational and formal operational stages. The Three Mountain Problem was devised by Piaget to test whether a child's thinking was egocentric, which was also a helpful indicator of whether the child was in the preoperational stage or the concrete operational stage of cognitive development.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Crain, William (2011). Theories of Development: Concepts and Applications (6th ed.). Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- 1 2 Piaget, Jean (1968) [1964]. Six psychological studies. Translated by Tenzer, Anita; Elkind, David. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- 1 2 3 Piaget, Jean; Szeminska, Alina (1941). The child's conception of number. Translated by Cattegno, C.; Hodgson, F. M. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

- ↑ Inhelder, Barbel (1971). "The criteria of the stages of mental development". In Tanner; Inhelder, Barbel (eds.). Discussions on child development. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

- ↑ Piaget, Jean (1969). "Piaget rediscovered". In Ripple; Rockcastle (eds.). Development and learning. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- ↑ Piaget, Jean (1959) [1923]. The language and thought of the child. Translated by Gabain, M. London, UK: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- ↑ Berger, Kathleen (2014). Invitation to the Life Span (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4641-7205-2.

- ↑ Piaget, Jean (1972) [1924]. Judgment and reasoning in the child. Translated by Warden, M. Savage, MD: Littlefield, Adams.

- ↑ Piaget, Jean (1963) [1926]. The child's conception of the world. Translated by Tomlinson, J.; Tomlinson A. Savage, MD: Littlefield, Adams.

- ↑ Piaget, Jean (1965) [1932]. The moral judgment of the child . Translated by Gabain, M. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-317-30591-3.

- 1 2 Helm-Estabrooks, Nancy (2004). "The problem of perseveration". Seminars in Speech and Language. 25 (4): 289–290. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-837241 . PMID 15599818.

- ↑ Winn, Philip (1941). Dictionary of Biological Psychology. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ Piaget, Jean; Inhelder, Barbel (1969). The psychology of the child . Translated by Weaver, H. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- ↑ Piaget, Jean; Inhelder, Barbel (1969). The psychology of the child . Translated by Weaver, H. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- ↑ Oswalt, Angela. Dombeck, Mark (ed.). "Cognitive Development: Piaget Part II". MentalHelp.net. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ Vasta, R.; Younger, A.J.; Adler, S.A.; Miller, S.A.; Ellis, S. (2009). Child Psychology (Second Canadian ed.). Mississauga, ON: John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd.

- ↑ Donaldson, Margaret (1982). "Conservation: What is the question?". British Journal of Psychology. 73 (2): 199–207. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1982.tb01802.x.

- ↑ Miller, Scott (1976). "Nonverbal assessment of Piagetian concepts". Psychological Bulletin. 83 (3): 405–430. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.83.3.405.

- ↑ Miller, Scott (1986). "Certainty and necessity in the understanding of Piagetian concepts". Developmental Psychology. 22: 3–18. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.1.3.

- ↑ Gelman, Rochel (1972). "Logical capacity of very young children: Number invariance rules". Child Development. 43 (1): 75–90. doi:10.2307/1127873. JSTOR 1127873.

- ↑ Halford, Graeme; Boyle, Frances (1985). "Do young children understand conservation of number?". Child Development. 56: 165–176. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1985.tb00095.x.