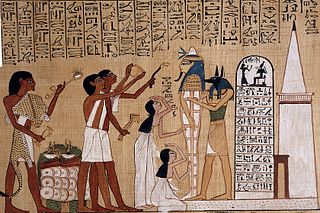

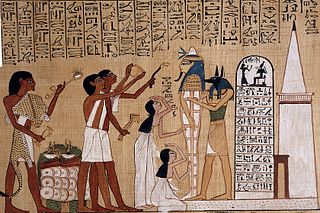

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect the dead, from interment, to various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in their honor. Customs vary between cultures and religious groups. Funerals have both normative and legal components. Common secular motivations for funerals include mourning the deceased, celebrating their life, and offering support and sympathy to the bereaved; additionally, funerals may have religious aspects that are intended to help the soul of the deceased reach the afterlife, resurrection or reincarnation.

A mastaba, also mastabah, mastabat or pr-djt, is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks. These edifices marked the burial sites of many eminent Egyptians during Egypt's Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom. In the Old Kingdom epoch, local kings began to be buried in pyramids instead of in mastabas, although non-royal use of mastabas continued for over a thousand years. Egyptologists call these tombs mastaba, from the Arabic word مصطبة (maṣṭaba) "stone bench".

Josefov is a town quarter and the smallest cadastral area of Prague, Czech Republic, formerly the Jewish ghetto of the town. It is surrounded by the Old Town. The quarter is often represented by the flag of Prague's Jewish community, a yellow Magen David on a red field.

Žižkov is a cadastral district of Prague, Czech Republic.

Ivančice is a town in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 9,700 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument zone.

Heřmanův Městec is a town in Chrudim District in the Pardubice Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 4,700 inhabitants. The historic town centre with the castle complex is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument zone.

The Sydney Town Hall is a late 19th-century heritage-listed town hall building in the city of Sydney, the capital city of New South Wales, Australia, housing the chambers of the Lord Mayor of Sydney, council offices, and venues for meetings and functions. It is located at 483 George Street, in the Sydney central business district opposite the Queen Victoria Building and alongside St Andrew's Cathedral. Sited above the Town Hall station and between the city shopping and entertainment precincts, the steps of the Town Hall are a popular meeting place.

The history of the Jews in Prague is one of Central Europe's oldest and most well-known. Prague boasts one of Europe's oldest recorded Jewish communities, first mentioned by a Mizrahi-Jewish traveller Ibrahim ibn Yaqub in 965. Since then, the community never ceased to exist, despite a number of pogroms and expulsions, the Holocaust, and subsequent antisemitic persecution by the Communist regime in the 20th century. Nowadays, the Jewish community of Prague numbers approximately 2,000 members. There are a number of synagogues of all Jewish denominations, a Chabad centre, an old age home, a kindergarten, Lauder Schools, Judaic Studies department at the Charles University, kosher restaurants and even a kosher hotel. Famous Jews from Prague include the Maharal, Franz Kafka, Miloš Forman and Madeleine Albright.

The Old Jewish Cemetery is a Jewish cemetery in Prague, Czech Republic, which is one of the largest of its kind in Europe and one of the most important Jewish historical monuments in Prague. It served its purpose from the first half of the 15th century until 1786. Renowned personalities of the local Jewish community were buried here; among them rabbi Jehuda Liva ben Becalel – Maharal, businessman Mordecai Meisel (1528–1601), historian David Gans and rabbi David Oppenheim (1664–1736). Today the cemetery is administered by the Jewish Museum in Prague.

Maisel Synagogue is one of the historical monuments of the former Prague Jewish quarter. It was built at the end of the 16th century which is considered to be the golden age of the ghetto. Since then its appearance has changed several times, its actual style is neo-gothic. Nowadays the synagogue belongs to the Jewish Community of Prague and is administered by the Jewish Museum in Prague as a part of its expositions.

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs, tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of ancestor veneration or as a publicly directed dynastic display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the lives of the living.

The Spanish Synagogue is the newest synagogue in the area of the so-called Jewish Town, yet paradoxically, it was built at the place of the presumably oldest synagogue, Old School. The synagogue is built in Moorish Revival Style. Only a little park with a modern statue of famous Prague writer Franz Kafka lies between it and the church of Holy Spirit. Today, the Spanish Synagogue is administered by the Jewish Museum in Prague.

The Jewish Museum in Prague is a museum of Jewish heritage in the Czech Republic and one of the most visited museums in Prague. Its collection of Judaica is one of the largest in the world, about 40,000 objects, 100,000 books, and a copious archive of Czech Jewish community histories.

The Smíchov Synagogue is the only functionalist synagogue in Prague; it was reconstructed to this style in 1931. After the World War II, the building was used for secular purposes because the Smíchov Jewish community ceased to exist in the Shoah. In the present, the building is used for an archive of the Jewish Museum in Prague.

The Mendelsohn House is a former Jewish Tahara house in Olsztyn (Allenstein), Poland, today used as a center for intercultural dialogue. It also includes a gatehouse.

The Pinkas Synagogue is the second oldest surviving synagogue in Prague. Its origins are connected with the Horowitz family, a renowned Jewish family in Prague. Today, the synagogue is administered by the Jewish Museum in Prague and commemorates about 78,000 Czech Jewish victims of the Shoah.

The Klausen Synagogue is nowadays the largest synagogue in the former Prague Jewish ghetto and the sole example of an early Baroque synagogue in the ghetto. Today the synagogue is administered by the Jewish Museum in Prague.

The Stolpersteine in Hranice na Moravě lists the Stolpersteine in the town Hranice na Moravě, Czech Republic. Stolpersteine is the German name for stumbling blocks collocated all over Europe by German artist Gunter Demnig. They remember the fate of the Nazi victims being murdered, deported, exiled or driven to suicide.

The Jewish Cemetery of Vukovar is a cemetery with approximately 75 to 100 remaining monuments which was used between 1850 and 1948. The oldest tombstone dates back to 1858 with multiple languages used in inscriptions including Hebrew, Hungarian, German and Croatian. The Ceremonial Hall or Zidduk-hadin was designed by Fran Funtak in Art-Deco and Moorish revival style. The first Jewish Cemetery in Vukovar was established in 1830.