Related Research Articles

Historical reenactments is an educational or entertainment activity in which mainly amateur hobbyists and history enthusiasts dress in historic uniforms and follow a plan to recreate aspects of a historical event or period. This may be as narrow as a specific moment from a battle, such as the reenactment of Pickett's Charge presented during the 1913 Gettysburg reunion, or as broad as an entire period, such as Regency reenactment.

Slavery in Canada includes historical practices of enslavement practised by both the First Nations until the 19th century, and by colonists during the period of European colonization.

A mammy is a U.S. historical stereotype depicting black women, usually enslaved, who did domestic work, including nursing children. The fictionalized mammy character is often visualized as a dark-skinned woman with a motherly personality. The origin of the mammy figure stereotype is rooted in the history of slavery in the United States, as slave women were often tasked with domestic and childcare work in American slave-holding households. The mammy caricature was used to create a narrative of black women being happy within slavery or within a role of servitude. The mammy stereotype associates black women with domestic roles and it has been argued that it, combined with segregation and discrimination, limited job opportunities for black women during the Jim Crow era, approximately 1877 to 1966.

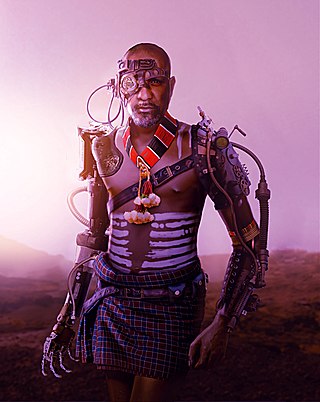

Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic, philosophy of science, and history that explores the intersection of the African diaspora culture with science and technology. It addresses themes and concerns of the African diaspora through technoculture and speculative fiction, encompassing a range of media and artists with a shared interest in envisioning black futures that stem from Afro-diasporic experiences. While Afrofuturism is most commonly associated with science fiction, it can also encompass other speculative genres such as fantasy, alternate history and magic realism. The term was coined by American cultural critic Mark Dery in 1993 and explored in the late 1990s through conversations led by Alondra Nelson.

Ruth Simmons is an American professor and academic administrator. Simmons served as the eighth president of Prairie View A&M University, a HBCU, from 2017 until 2023. From 2001 to 2012, she served as the 18th president of Brown University, where she was the first African American president of an Ivy League institution. While there, Simmons was named, best college president by Time magazine. Before Brown University, she headed Smith College, one of the Seven Sisters and the largest women's college in the United States, beginning in 1995. There, during her presidency, the first accredited program in engineering was started at an all-women's college.

Islamic views on slavery represent a complex and multifaceted body of Islamic thought, with various Islamic groups or thinkers espousing views on the matter which have been radically different throughout history. Slavery was a mainstay of life in pre-Islamic Arabia and surrounding lands. The Quran and the hadith address slavery extensively, assuming its existence as part of society but viewing it as an exceptional condition and restricting its scope. Early Islamic dogma forbade enslavement of dhimmis, the free members of Islamic society, including non-Muslims and set out to regulate and improve the conditions of human bondage. Islamic law regarded as legal slaves only those non-Muslims who were imprisoned or bought beyond the borders of Islamic rule, or the sons and daughters of slaves already in captivity. In later classical Islamic law, the topic of slavery is covered at great length.

The Institute for Colored Youth was founded in 1837 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. It became the first college for African-Americans in the United States, although there were schools that admitted African Americans preceding it. At the time, public policy and certain statutory provisions prohibited the education of blacks in various parts of the nation and slavery was entrenched across the south. It was followed by two other black institutions— Lincoln University in Pennsylvania (1854), and Wilberforce University in Ohio (1856). The second site of the Institute for Colored Youth at Ninth and Bainbridge Streets in Philadelphia was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. It is also known as the Samuel J. Randall School. A three-story, three-bay brick building was built for it in 1865, in the Italianate-style After moving to Cheyney, Pennsylvania in Delaware County, Pennsylvania its name was changed to Cheyney University.

Laura Wheeler Waring was an American artist and educator, most renowned for her realistic portraits, landscapes, still-life, and well-known African American portraitures she made during the Harlem Renaissance. She was one of the few African American artists in France, a turning point of her career and profession where she attained widespread attention, exhibited in Paris, won awards, and spent the next 30 years teaching art at Cheyney University in Pennsylvania.

Black science fiction or black speculative fiction is an umbrella term that covers a variety of activities within the science fiction, fantasy, and horror genres where people of the African diaspora take part or are depicted. Some of its defining characteristics include a critique of the social structures leading to black oppression paired with an investment in social change. Black science fiction is "fed by technology but not led by it." This means that black science fiction often explores with human engagement with technology instead of technology as an innate good.

Belinda Sutton, also known as Belinda Royall, was a Ghanaian-born woman who was enslaved by the Royall family at the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Massachusetts, USA. Additional details of Sutton's family life are under ongoing research. Baptism records for a son Joseph, and a daughter Prine, appear in church records. Belinda was abandoned by, Isaac Royall Jr., when he fled to Nova Scotia at the beginning of the American Revolution. In Royall's will, a number of enslaved people are listed, but Belinda was unique in his wishes:

"In his will he gave his slave Belinda the option of freedom, and he further 'provided that she get security that she shall not be a charge in the town of Medford.' If she did not elect freedom, he bequeathed her to his daughter Mary Erving. Other slaves were bequeathed and some were sold, but Belinda was emancipated."

The term Chicanafuturism was originated by scholar Catherine S. Ramírez which she introduced in Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies in 2004. The term is a portmanteau of 'chicana' and 'futurism', inspired by the developing movement of Afrofuturism. The word 'chicana' refers to a woman or girl of Mexican origin or descent. However, 'Chicana' itself serves as a chosen identity for many female Mexican Americans in the United States, to express self-determination and solidarity in a shared cultural, ethnic, and communal identity while openly rejecting assimilation. Ramírez created the concept of Chicanafuturism as a response to white androcentrism that she felt permeated science-fiction and American society. Chicanafuturism can be understood as part of a larger genre of Latino futurisms.

Fabiola Jean-Louis is a Haitian artist working in photography, paper textile design, and sculpture. Her work examines the intersectionality of the Black experience, particularly that of women, to address the absence and imbalance of historical representation of African American and Afro-Caribbean people. Jean-Louis has earned residencies at the Museum of Art and Design (MAD), New York City, the Lux Art Institute, San Diego, and the Andrew Freedman Home in The Bronx. In 2021, Jean-Louis became the first Haitian woman artist to exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Fabiola lives and works in New York City.

The Deep is a 2019 fantasy book by Rivers Solomon, with Daveed Diggs, William Hutson and Jonathan Snipes. It depicts an underwater society built by the water-breathing descendants of pregnant slaves thrown overboard from slave ships. The book was developed from a song of the same name by Clipping, an experimental hip-hop trio. It won the Lambda Literary Award, and was nominated for Hugo, Nebula and Locus awards.

Africanfuturism is a cultural aesthetic and philosophy of science that centers on the fusion of African culture, history, mythology, point of view, with technology based in Africa and not limiting to the diaspora. It was coined by Nigerian American writer Nnedi Okorafor in 2019 in a blog post as a single word. Nnedi Okorafor defines Africanfuturism as a sub-category of science fiction that is "directly rooted in African culture, history, mythology and point-of-view..and...does not privilege or center the West," is centered with optimistic "visions in the future," and is written by "people of African descent" while rooted in the African continent. As such its center is African, often does extend upon the continent of Africa, and includes the Black diaspora, including fantasy that is set in the future, making a narrative "more science fiction than fantasy" and typically has mystical elements. It is different from Afrofuturism, which focuses mainly on the African diaspora, particularly the United States. Works of Africanfuturism include science fiction, fantasy, alternate history, horror and magic realism.

Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room is an art exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The exhibit, which opened on November 5, 2021, uses a period room format of installation to envision the past, present, and future home of someone who lived in Seneca Village, a largely African American settlement which was destroyed to make way for the construction of Central Park in the mid-1800s.

Mary Bateman Clark (1795–1840) was an American woman, born into slavery, who was taken to Indiana Territory. She was forced to become an indentured servant, even though the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery. She was sold in 1816, the same year that the Constitution of Indiana prohibited slavery and indentured servitude. In 1821, attorney Amory Kinney represented her as she fought for her freedom in the courts. After losing the case in the Circuit Court, she appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court in the case of Mary Clark v. G.W. Johnston. She won her freedom with the precedent-setting decision against indentured servitude in Indiana. The documentary, Mary Bateman Clark: A Woman of Colour and Courage, tells the story of her life and fight for freedom.

Michelle D. Commander is a historian and author, and serves as Deputy Director of Research and Strategic Initiatives at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Spellings, Sarah (2023-03-08). "For These Women of Color, Historical Dressing Is a Modern Art Form". Vogue. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Beery, Zoë. "Say goodbye to your happy plantation narrative". The Outline. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- 1 2 "Changing the Narrative of Slavery with Cheyney McKnight '11 | Simmons University". www.simmons.edu. 13 February 2019. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "Historic interpreters are changing the conversation about race". Travel. 2020-09-25. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ Rafferty, Rebecca. "Genesee Country Village & Museum reckons with representation". CITY News. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "'Meet the Revolution' Series Sheds Light on the Lives of Revolutionary-Era Black Women and Men this Summer". Museum of the American Revolution. 22 July 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Nadal, Emily (2022-06-13). "Cheyney McKnight just wants to relax and celebrate on Juneteenth". www.audacy.com. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- 1 2 Endter, Kelsey (2021-04-27). "Historical Interpreter Brings Black History Into The Spotlight". Cosplay Central. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ Fernando, Christine (27 March 2021). "Many history interpreters of color carry weight of racism". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "Living History: Cooking Spooky Treats with Ms. Cheyney". www.nyhistory.org. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "LET'S LEARN: Objects and Money from Long Ago". PBS. 3 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- 1 2 Rougeau, Naomi (2021-07-22). "Are You Over Normcore? Meet Its Fancy Sibling, Regency-Core". ELLE. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "This Woman Is Making Sure Historical Reenactments Get Slavery Right". Racked. 2018-02-14. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "Introducing "The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty"". American Duchess Blog. 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ McKnight, Cheyney (25 April 2022). "An Afrofuturist Journey Through History". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ↑ "NotYourMommasHistory". YouTube. Retrieved 23 April 2023.