Related Research Articles

A gift economy or gift culture is a system of exchange where valuables are not sold, but rather given without an explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards. Social norms and customs govern giving a gift in a gift culture; although there is some expectation of reciprocity, gifts are not given in an explicit exchange of goods or services for money, or some other commodity or service. This contrasts with a barter economy or a market economy, where goods and services are primarily explicitly exchanged for value received.

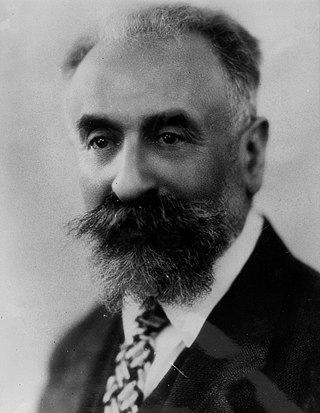

Bronisław Kasper Malinowski was a Polish-British anthropologist and ethnologist whose writings on ethnography, social theory, and field research have exerted a lasting influence on the discipline of anthropology.

Marshall David Sahlins was an American cultural anthropologist best known for his ethnographic work in the Pacific and for his contributions to anthropological theory. He was the Charles F. Grey Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and of Social Sciences at the University of Chicago.

The Trobriand Islands are a 450-square-kilometre (174-square-mile) archipelago of coral atolls off the east coast of New Guinea. They are part of the nation of Papua New Guinea and are in Milne Bay Province. Most of the population of 12,000 indigenous inhabitants live on the main island of Kiriwina, which is also the location of the government station, Losuia.

Economic anthropology is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology began with work by the Polish founder of anthropology Bronislaw Malinowski and the French Marcel Mauss on the nature of reciprocity as an alternative to market exchange. For the most part, studies in economic anthropology focus on exchange.

Marcel Mauss was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today, he is perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter discipline, particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as magic, sacrifice and gift exchange in different cultures around the world. Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology. His most famous work is The Gift (1925).

Maurice Godelier is a French anthropologist who works as a Director of Studies at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences. He is one of the most influential French anthropologists and is best known as one of the earliest advocates of Marxism's incorporation into anthropology. He is also known for his field work among the Baruya in Papua New Guinea from the 1960s to the 1980s.

The Moka is a highly ritualized system of exchange in the Mount Hagen area, Papua New Guinea, that has become emblematic of the anthropological concepts of "gift economy" and of "Big man" political system. Moka are reciprocal gifts of pigs through which social status is achieved. Moka refers specifically to the increment in the size of the gift; giving more brings greater prestige to the giver. However, reciprocal gift giving was confused by early anthropologists with profit-seeking, as the lending and borrowing of money at interest.

In economics, a market is a composition of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations or infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering their goods or services to buyers in exchange for money. It can be said that a market is the process by which the prices of goods and services are established. Markets facilitate trade and enable the distribution and allocation of resources in a society. Markets allow any tradeable item to be evaluated and priced. A market emerges more or less spontaneously or may be constructed deliberately by human interaction in order to enable the exchange of rights of services and goods. Markets generally supplant gift economies and are often held in place through rules and customs, such as a booth fee, competitive pricing, and source of goods for sale.

Dame Ann Marilyn Strathern, DBE, FBA is a British anthropologist, who has worked largely with the Mount Hagen people of Papua New Guinea and dealt with issues in the UK of reproductive technologies. She was William Wyse Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge from 1993 to 2008, and Mistress of Girton College, Cambridge from 1998 to 2009.

Peter D. Dwyer is an anthropologist and zoologist. He is an honorary research fellow at the University of Melbourne in Australia. He was Reader in Zoology at the University of Queensland, retiring in 1997.

"Gifting remittances" describes a range of scholarly approaches relating remittances to anthropological literature on gift giving. The terms draws on Lisa Cliggett's "gift remitting", but is used to describe a wider body of work. Broadly speaking, remittances are the money, goods, services, and knowledge that migrants send back to their home communities or families. Remittances are typically considered as the economic transactions from migrants to those at home. While remittances are also a subject of international development and policy debate and sociological and economic literature, this article focuses on ties with literature on gifting and reciprocity or gift economy founded largely in the work of Marcel Mauss and Marshall Sahlins. While this entry focuses on remittances of money or goods, remittances also take the form of ideas and knowledge. For more on these, see Peggy Levitt's work on "social remittances" which she defines as "the ideas, behaviors, identities, and social capital that flow from receiving to sending country communities."

Inalienable possessions are things such as land or objects that are symbolically identified with the groups that own them and so cannot be permanently severed from them. Landed estates in the Middle Ages, for example, had to remain intact and even if sold, they could be reclaimed by blood kin. As a legal classification, inalienable possessions date back to Roman times. According to Barbara Mills, "Inalienable possessions are objects made to be kept, have symbolic and economic power that cannot be transferred, and are often used to authenticate the ritual authority of corporate groups".

Indonesia–Papua New Guinea relations are foreign relations between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, two bordering countries north of Australia.

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In the United States, social anthropology is commonly subsumed within cultural anthropology or sociocultural anthropology.

Political economy in anthropology is the application of the theories and methods of historical materialism to the traditional concerns of anthropology, including but not limited to non-capitalist societies. Political economy introduced questions of history and colonialism to ahistorical anthropological theories of social structure and culture. Most anthropologists moved away from modes of production analysis typical of structural Marxism, and focused instead on the complex historical relations of class, culture and hegemony in regions undergoing complex colonial and capitalist transitions in the emerging world system.

The Development Policy Centre (Devpol) is an aid and development policy think tank based at the Crawford School of Public Policy in the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University. Devpol undertakes independent research and promotes practical initiatives to improve the effectiveness of Australian aid, to support the development of Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands region, and to contribute to better global development policy.

Marie Olive Reay was an Australian anthropologist, known particularly for work in the New Guinea Highlands.

Susanne Kuehling is a scholar of anthropology and ethnology. She currently works at the University of Regina.

Michelle Nayahamui Rooney has dual Papua New Guinean and Australian nationality. She is a research fellow at the Development Policy Centre of the Australian National University and publishes extensively on matters relating to Papua New Guinea (PNG) and the Pacific islands.

References

- ↑ Director (Research Services Division). "Dr Christopher Gregory". researchers.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ "The Domestic Moral Economy - School of Social Sciences - The University of Manchester". www.socialsciences.manchester.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Ingold, Tim (1994). Companion encyclopedia of anthropology. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415021371. OCLC 51874027.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gregory, C. A. (Chris) (1997). Savage money : the anthropology and politics of commodity exchange. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. ISBN 9789057020926. OCLC 37918055.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gregory, C. A. (Chris) (2015). Gifts and commodities. Strathern, Marilyn (Second ed.). Chicago, IL. ISBN 9780990505013. OCLC 891618291.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Golub, Alex. "What you need to know about HAU Books". Archived from the original on 24 October 2016.

- ↑ "Gifts and Commodities- HAU Books". Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Otto, Ton; Willerslev, Rane (1 March 2013). "Introduction: "Value as theory": Comparison, cultural critique, and guerilla ethnographic theory". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 3 (1): 1–20. doi:10.14318/hau3.1.002. ISSN 2575-1433. S2CID 59935483.

- ↑ "Money: One Anthropologist's View – The Memory Bank". thememorybank.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Graeber, David (2011). Debt : the first 5,000 years . Brooklyn, N.Y.: Melville House. ISBN 9781933633862. OCLC 426794447.

- ↑ "Australian Envoy Marks White Ribbon Day with Launch of Handbook". Australian High Commission: Fiji. 25 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.