Related Research Articles

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orchestras or concerts. Its most common form is triangular in shape and made of wood. Some have multiple rows of strings and pedal attachments.

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

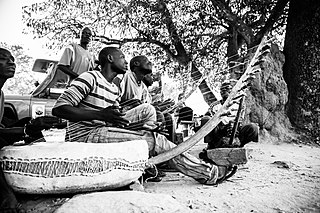

The musical bow is a simple string instrument used by a number of South African peoples, which is also found in the Americas via slave trade. It consists of a flexible, usually wooden, stick 1.5 to 10 feet long, and strung end to end with a taut cord, usually metal. It can be played with the hands or a wooden stick or branch. It is uncertain if the musical bow developed from the hunting bow, though the San or Bushmen people of the Kalahari Desert do convert their hunting bows to musical use.

Kyrgyz music is nomadic and rural, and is closely related to Turkmen and Kazakh folk forms. Kyrgyz folk music is characterized by the use of long, sustained pitches, with Russian elements also prominent.

Scotland is internationally known for its traditional music, which remained vibrant throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, when many traditional forms worldwide lost popularity to pop music. Despite emigration and a well-developed connection to music imported from the rest of Europe and the United States, the music of Scotland has kept many of its traditional aspects and has influenced many other forms of music.

Music was ubiquitous throughout Mesopotamian history, playing important roles in both religious and secular contexts. Mesopotamia is of particular interest to scholars because evidence from the region—which includes artifacts, artistic depictions, and written records—places it among the earliest well-documented cultures in the history of music. The discovery of a bone wind instrument dating to the 5th millennium BCE provides the earliest evidence of music culture in Mesopotamia; depictions of music and musicians appear in the 4th millennium BCE; and later, in the city of Uruk, the pictograms for ‘harp’ and ‘musician’ are present among the earliest known examples of writing.

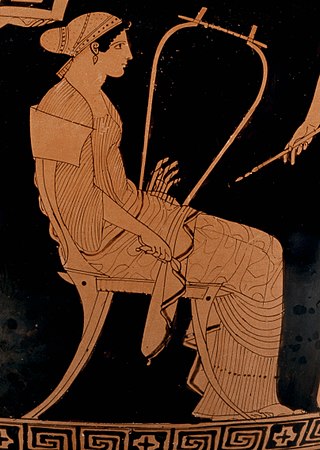

The barbiton, or barbitos, is an ancient stringed instrument related to the lyre known from Greek and Roman classics.

The Celtic harp is a triangular frame harp traditional to the Celtic nations of northwest Europe. It is known as cláirseach in Irish, clàrsach in Scottish Gaelic, telenn in Breton and telyn in Welsh. In Ireland and Scotland, it was a wire-strung instrument requiring great skill and long practice to play, and was associated with the Gaelic ruling class. It appears on Irish coins, Guinness products, and the coat of arms of the Republic of Ireland, Montserrat, Canada and the United Kingdom.

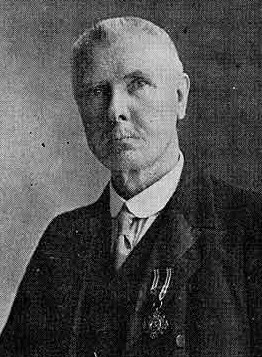

Chevalier William Henry Grattan Flood was a noted Irish author, composer, musicologist and historian. As a writer and ecclesiastical composer, his personal contributions to Irish music produced enduring works, although he is regarded today as controversial due to the inaccuracy of some of his work. As a historian, his output was prolific on topics of local and national historical or biographical interest.

A glass harp is a musical instrument made of upright wine glasses.

Irish traditional music is a genre of folk music that developed in Ireland.

Angular harp is a category of musical instruments in the Hornbostel-Sachs system of musical instrument classification. It describes a harp in which "the neck makes a sharp angle with the resonator," the two arms forming an "open" harp. The harp stands in contrast to the arched harp or bow harp in which the angle is much less sharp and in which the neck curves away from the resonator. It also stands in contrast to the frame harp which is a "closed harp" and in which there is no opening between the resonator and the upper tip of the harp, but has a third side forming a triangle.

African Harps, particularly arched or "bow" harps, are found in several Sub-Saharan African music traditions, particularly in the north-east. Used from early times in Africa, they resemble the form of harps in ancient Egypt with a vaulted body of wood, parchment faced, and a neck, perpendicular to the resonant face, on which the strings are wound.

The yazh is a harp used in ancient Tamil music. It was strung with gut strings that ran from an curved ebony neck to a boat or trough-shaped resonator, the opening of which was a covered with skin for a soundboard. At the resonator the strings were attached to a string-bar or tuning bar with holes for strings that laid beneath of the soundboard and protruded through. The neck may also have been covered in hide.

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who plays a musical instrument is known as an instrumentalist. The history of musical instruments dates to the beginnings of human culture. Early musical instruments may have been used for rituals, such as a horn to signal success on the hunt, or a drum in a religious ceremony. Cultures eventually developed composition and performance of melodies for entertainment. Musical instruments evolved in step with changing applications and technologies.

The veena, also spelled vina, comprises various chordophone instruments from the Indian subcontinent. Ancient musical instruments evolved into many variations, such as lutes, zithers and arched harps. The many regional designs have different names such as the Rudra veena, the Saraswati veena, the Vichitra veena and others.

Music in Medieval Scotland includes all forms of musical production in what is now Scotland between the fifth century and the adoption of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. The sources for Scottish Medieval music are extremely limited. There are no major musical manuscripts for Scotland from before the twelfth century. There are occasional indications that there was a flourishing musical culture. Instruments included the cithara, tympanum, and chorus. Visual representations and written sources demonstrate the existence of harps in the Early Middle Ages and bagpipes and pipe organs in the Late Middle Ages. As in Ireland, there were probably filidh in Scotland, who acted as poets, musicians and historians. After this "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court in the twelfth century, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Scottish Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century.

The mandolin is a modern member of the lute family, dating back to Italy in the 18th century. The instrument was played across Europe but then disappeared after the Napoleonic Wars. Credit for creating the modern bowlback version of the instrument goes to the Vinaccia family of Naples. The deep bowled mandolin, especially the Neapolitan form, became common in the 19th century, following the appearance of an international hit, the Spanish Students. They toured Europe and America, and their performances created a stir that helped the mandolin to become widely popular.

The psalterion is a stringed, plucked instrument, an ancient Greek harp. Psalterion was a general word for harps in the latter part of the 4th century B.C. It meant "plucking instrument".

References

- ↑ Nora Joan Clark (1 November 2003). The story of the Irish harp: its history and influence. North Creek Press. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-9724202-0-4 . Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ↑ William Henry Grattan Flood (1905). The story of the harp. Scott. pp. 9–. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ↑ Carl Engel (1876). Musical instruments ... Scribner, Welford, and Armstrong. pp. 93–. Retrieved 6 April 2011.