Rebecca is a biblical matriarch.

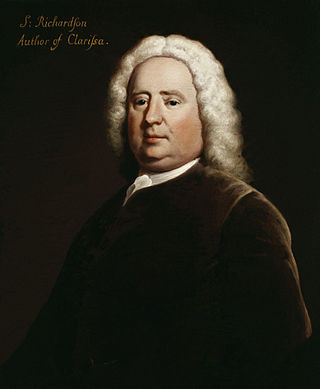

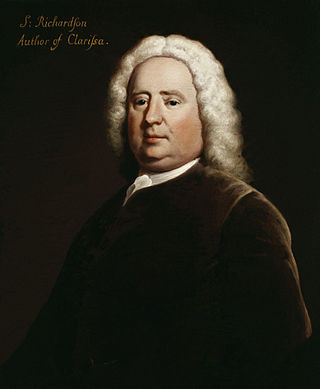

Samuel Richardson was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady (1748) and The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753). He printed almost 500 works, including journals and magazines, working periodically with the London bookseller Andrew Millar. Richardson had been apprenticed to a printer, whose daughter he eventually married. He lost her along with their six children, but remarried and had six more children, of whom four daughters reached adulthood, leaving no male heirs to continue the print shop. As it ran down, he wrote his first novel at the age of 51 and joined the admired writers of his day. Leading acquaintances included Samuel Johnson and Sarah Fielding, the physician and Behmenist George Cheyne, and the theologian and writer William Law, whose books he printed. At Law's request, Richardson printed some poems by John Byrom. In literature, he rivalled Henry Fielding; the two responded to each other's literary styles.

Stella or STELLA may refer to:

Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life. And Particularly Shewing, the Distresses that May Attend the Misconduct Both of Parents and Children, In Relation to Marriage is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson, published in 1748. The novel tells the tragic story of a young woman, Clarissa Harlowe, whose quest for virtue is continually thwarted by her family. The Harlowes are a recently wealthy family whose preoccupation with increasing their standing in society leads to obsessive control of their daughter, Clarissa. It is considered one of the longest novels in the English language. It is generally regarded as Richardson's masterpiece.

The History of Sir Charles Grandison, commonly called Sir Charles Grandison, is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson first published in February 1753. The book was a response to Henry Fielding's The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, which parodied the morals presented in Richardson's previous novels. The novel follows the story of Harriet Byron who is pursued by Sir Hargrave Pollexfen. After she rejects Pollexfen, he kidnaps her, and she is only freed when Sir Charles Grandison comes to her rescue. After his appearance, the novel focuses on his history and life, and he becomes its central figure.

The Wild Boys may refer to:

Harlow is a town in Essex, England.

August is the eighth month of the year.

Clarissa is a female given name borrowed from Latin, Italian, and Portuguese, originally denoting a nun of the Roman Catholic Order of St. Clare. It is a combination of St. Clare of Assisi's Latin name Clara and the suffix -issa, equivalent to -ess. Clarice is an anglicization of Clarisse, the French form of the same name. Clarisa is the Spanish form of the name, and Klárisza the Hungarian. The given names Clara, Clare, and Claire are all cognates, as are the surnames Sinclair and St. Clair.

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.