Related Research Articles

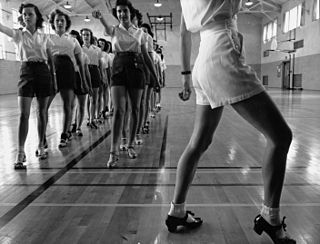

Tap dance is a form of dance that uses the sounds of tap shoes striking the floor as a form of percussion; it is often accompanied by music. Tap dancing can also be a cappella, with no musical accompaniment; the sound of the taps is its own music.

The Nicholas Brothers were an entertainment act composed of brothers, Fayard (1914–2006) and Harold (1921–2000), who excelled in a variety of dance techniques, primarily between the 1930s and 1950s. Best known for their unique interpretation of a highly acrobatic technique known as "flash dancing", they were also considered by many to be the greatest tap dancers of their day, if not all time. Their virtuoso performance in the musical number "Jumpin' Jive" featured in the 1943 movie Stormy Weather has been praised as one of the greatest dance routines ever captured on film.

Dianne Walker, also known as Lady Di, is an American tap dancer. Her thirty-year career spans Broadway, television, film, and international dance concerts. Walker is the artistic director of TapDancin, Inc. in Boston, Massachusetts.

Charles "Cholly" Atkins was an American dancer and vaudeville performer, who later became noted as the house choreographer for the various artists on the label Motown.

James Titus Godbolt, known professionally as Jimmy Slyde and also as the "King of Slides", was an American tap dancer known for his innovative tap style mixed with jazz.

Brenda Bufalino is an American tap dancer and writer. She co-founded, choreographed and directed the American Tap Dance Foundation, known at the time as the American Tap Dance Orchestra. Bufalino wrote a memoir entitled, Tapping the Source...Tap dance, Stories, Theory and Practice and a book of poems Circular Migrations, both of which have been published by Codhill Press, and the novella Song of the Split Elm, published by Outskirts Press.

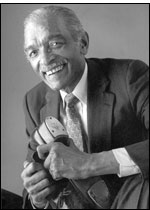

Charles "Honi" Coles was an American actor and tap dancer, who was inducted posthumously into the American Tap Dance Hall of Fame in 2003. He had a distinctive personal style that required technical precision, high-speed tapping, and a close-to-the-floor style where "the legs and feet did the work". Coles was also half of the professional tap dancing duo Coles and Atkins, whose specialty was performing with elegant style through various tap steps such as "swing dance", "over the top", "bebop", "buck and wing", and "slow drag".

Black and Blue is a musical revue celebrating the black culture of dance and music in Paris between World War I and World War II.

LeRoy Myers was an African American tap dancer and manager of the Copasetics. He was born in North Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and learned to tap dance on the street corners of Philadelphia.

The Hoofers Club was an African-American entertainment establishment and dancers' club hangout in Harlem, New York, that ran from the early 1920s until the early 1940s. It was founded and managed by Lonnie Hicks (1882–1953), an Atlanta-born ragtime pianist.

Ernest "Brownie" Brown was an African American tap dancer and last surviving member of the Original Copasetics. He was the dance partner of Charles "Cookie" Cook, with whom he performed from the days of vaudeville into the 1960s, and of Reginald McLaughlin, also known as "Reggio the Hoofer," from 1996 until Brown's death in 2009.

Charles “Cookie” Cook was a tap dancer who performed in the heyday of tap through the 1980s, and was a founding member of the Copasetics. He was the dance partner of Ernest “Brownie” Brown, with whom he performed from the days of vaudeville into the 1960s. They performed in film, such as Dorothy Dandridge 1942 “soundie” Cow Cow Boogie, on Broadway in the 1948 musical Kiss Me, Kate, twice at the Newport Jazz Festival, as well in other acts, including “Garbage and His Two Cans” in which they played the garbage cans. He headlined venues including New York's Palace, the Apollo, Radio City Music Hall, Cotton Club, and London Palladium. Quoted as saying “if you can walk, you can dance,” Cook was one of the most influential tap masters and crucial in passing on the tap tradition to future generations.

The Original Copasetics were an ensemble of star tap dancers formed in 1949 on the death of Bill Bojangles Robinson that helped to revive the art of tap. The first group included composer/arranger Billy Strayhorn and the choreographer Cholly Atkins, as well as Honi Coles, Charles “Cookie” Cook and his dance partner Ernest “Brownie” Brown. Other dancers included Chuck Green, Jimmy Slyde, Buster Brown and Howard “Sandman” Sims. The group took its name from Robinson’s familiar observation that “everything is copasetic” and was honored in the 1989 Broadway revue Black and Blue.

The Flo-Bert Award honors "outstanding figures in the field of tap dance".

The American Tap Dance Foundation is a nonprofit organization whose primary goal is the presentation and teaching of tap dance. Its original stated purpose was to provide an "international home for tap dance, perpetuate tap as a contemporary art form, preserve it through performance and an archival library, provide educational programming, and establish a formal school for tap dance."

Tap City, the New York City Tap Festival, was launched in 2001 in New York City. Held annually for approximately one week each summer, the festival features tap dancing classes, choreography residencies, panels, screenings, and performances as well as awards ceremonies, concert performances, and Tap it Out, a free, public, outdoor event performed in Times Square by a chorus of dancers. The goal of the Festival is to establish a "higher level of understanding and examination of tap’s storied history and development.”

The Paradise Club or Club Paradise was a nightclub and jazz club at 220 North Illinois Avenue in Atlantic City, New Jersey. It was one of two major black jazz clubs in Atlantic City during its heyday from the 1920s through 1950s, the other being Club Harlem. Entertaining a predominantly white clientele, it was known for its raucous floor shows featuring gyrating black dancers accompanied by high-energy jazz bands led by the likes of Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, and Lucky Millinder. In 1954 the Paradise Club merged with Club Harlem under joint ownership.

The Cotton Club Boys were African American chorus line entertainers who, from 1934, performed class act dance routines in musical revues produced by the Cotton Club until 1940, when the club closed, then as part of Cab Calloway's revue on tour through 1942.

The Nest Club was a cabaret in Harlem, more specifically an afterhours club, at 169 West 133rd Street – a street known then both as "Swing Street" and "Jungle Alley" – two doors east of Seventh Avenue, downstairs. The club, operating under the auspices of The Nest Club, Inc., was founded in 1923, co-owned, and operated by John C. Carey (né John Clifford Carey; 1889–1956) and Mal Frazier (né Melville Hunter Frazier; 1888–1967). The club flourished through 1933. The U.S. Prohibition — a nationwide ban on the sale of alcoholic beverages — ran from 1920 to 1933. The club faced a formidable challenge to its viability following the Great Crash of October 1929, followed by the Great Depression that bottomed around March 1933.

Miller Brothers and Lois, a renowned tap dance class act team, comprising Danny Miller, George Miller and Lois Bright, was a peak of platform dancing with the tall and graceful Lois said to distinguish the trio. The group performed the majority of their act on platforms of various heights, with the initial platform spelling out M-I-L-L-E-R. They performed over-the-tops, barrel turns and wings on six-foot-high pedestals. They toured theatres coast to coast with Jimmy Lunceford and his Orchestra, Cab Calloway and his Orchestra, and the Count Basie Band.

References

- 1 2 3 Class Act: The Jazz Life of Choreographer Cholly Atkins (memoir), by Cholly Atkins & Jacqui Malone, Columbia University Press (2001), pg. 114; OCLC 974087440 "Class act" (discussion) (alternate link) pg. 114Note: Malone, a dance and theater scholar at Queens College, married, in 1973, Robert George O'Meally, PhD, American literature scholar and Zora Neale Hurston Professor of Literature at Columbia University, who, additionally, writes about jazz

"Class act" (defined) (alternate link), pg. 226

"Flash act" (defined) (alternate link), pg. 227 - ↑ Black Dance, by Edward ("Ted") Thorpe (né Edward Robert Thorpe; born 1926) (retired sometime before 1995, was a dance critic for the London Evening Standard; he has been married to Gillian Freeman, a writer, for 69 years)

- ↑ What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing, by Brian Seibert, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2016) pps. 180, 200, 307

- ↑ "Class Act," Performing Arts Encyclopedia c/o Library of Congress (online); OCLC 76944288, 54373218

- ↑ "Over the Top to Be-Bop Camera Three , Season 10, Episode 18, CBS

Aired Sunday, 11:30 am, 3 January 1965

Produced for WCBS-TV by Dan Gallagher

Nick Havinga (né Nicholas Havinga, Jr.; born 1935), director- Featured artists: Coles and Cholly Atkins (dance duet)

- Other performers: Hank Jones (piano)

- James Fergus Macandrew (1906–1988) (program host)

- Guest: Marshall Stearns, PhD

New York State Education Dept (1965); OCLC 19009050

Creative Arts Television (VHS) (19??); OCLC 38594171

Creative Arts Television (VHS) (1997); OCLC 41462387, 50611853

Creative Arts Television (DVD) (2007); OCLC 181202686, 174151608

Aviva Films Ltd. (digital) (2007); OCLC 830519421 - ↑ "'Let the Punishment Fit the Crime': The Vocal Choreography of Cholly Atkins," by Jacqui Malone (MCP) (née Jacqueline Delores Malone; born 1947), Dance Research Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1, Summer 1988, pps. 11–18 (retrieved 24 March 2017; stable URL www

.jstor .org /stable /1478812 ) - ↑ Tappin' at the Apollo: The African American Female Tap Dance Duo Salt and Pepper, by Cheryl M. Willis, McFarland & Company (2016), pg. 213; OCLC 917343455

- 1 2 Brotherhood in Rhythm: The Jazz Tap Dancing of the Nicholas Brothers, by Constance Valis Hill, PhD (born 1947), Cooper Square Press (2002), pps. 134; OCLC 845250422

- ↑ Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History (alternate link 1; alt link 2) by Constance Valis Hill, PhD (born 1947), Oxford University Press (2010), pps. 41–42; OCLC 888554987

- ↑ "Johnson, John Rosamond" (alt link), Cary D. Wintz & Paul Finkelman (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance (Vol. 1 of 2; A–J), Routledge (2004), pg. 636; OCLC 648136726, 56912455