Chromosomal crossover, or crossing over, is the exchange of genetic material during sexual reproduction between two homologous chromosomes' non-sister chromatids that results in recombinant chromosomes. It is one of the final phases of genetic recombination, which occurs in the pachytene stage of prophase I of meiosis during a process called synapsis. Synapsis begins before the synaptonemal complex develops and is not completed until near the end of prophase I. Crossover usually occurs when matching regions on matching chromosomes break and then reconnect to the other chromosome.

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and the second recessive. This state of having two different variants of the same gene on each chromosome is originally caused by a mutation in one of the genes, either new or inherited. The terms autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive are used to describe gene variants on non-sex chromosomes (autosomes) and their associated traits, while those on sex chromosomes (allosomes) are termed X-linked dominant, X-linked recessive or Y-linked; these have an inheritance and presentation pattern that depends on the sex of both the parent and the child. Since there is only one copy of the Y chromosome, Y-linked traits cannot be dominant or recessive. Additionally, there are other forms of dominance such as incomplete dominance, in which a gene variant has a partial effect compared to when it is present on both chromosomes, and co-dominance, in which different variants on each chromosome both show their associated traits.

Genetic recombination is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryotes, genetic recombination during meiosis can lead to a novel set of genetic information that can be further passed on from parents to offspring. Most recombination occurs naturally and can be classified into two types: (1) interchromosomal recombination, occurring through independent assortment of alleles whose loci are on different but homologous chromosomes ; & (2) intrachromosomal recombination, occurring through crossing over.

Fitness is the quantitative representation of individual reproductive success. It is also equal to the average contribution to the gene pool of the next generation, made by the same individuals of the specified genotype or phenotype. Fitness can be defined either with respect to a genotype or to a phenotype in a given environment or time. The fitness of a genotype is manifested through its phenotype, which is also affected by the developmental environment. The fitness of a given phenotype can also be different in different selective environments.

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and population structure.

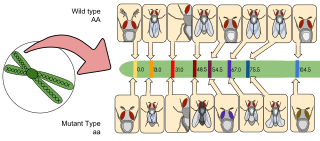

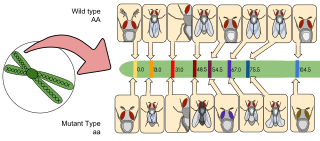

Genetic linkage is the tendency of DNA sequences that are close together on a chromosome to be inherited together during the meiosis phase of sexual reproduction. Two genetic markers that are physically near to each other are unlikely to be separated onto different chromatids during chromosomal crossover, and are therefore said to be more linked than markers that are far apart. In other words, the nearer two genes are on a chromosome, the lower the chance of recombination between them, and the more likely they are to be inherited together. Markers on different chromosomes are perfectly unlinked, although the penetrance of potentially deleterious alleles may be influenced by the presence of other alleles, and these other alleles may be located on other chromosomes than that on which a particular potentially deleterious allele is located.

In population genetics, linkage disequilibrium (LD) is the non-random association of alleles at different loci in a given population. Loci are said to be in linkage disequilibrium when the frequency of association of their different alleles is higher or lower than what would be expected if the loci were independent and associated randomly.

Genetic load is the difference between the fitness of an average genotype in a population and the fitness of some reference genotype, which may be either the best present in a population, or may be the theoretically optimal genotype. The average individual taken from a population with a low genetic load will generally, when grown in the same conditions, have more surviving offspring than the average individual from a population with a high genetic load. Genetic load can also be seen as reduced fitness at the population level compared to what the population would have if all individuals had the reference high-fitness genotype. High genetic load may put a population in danger of extinction.

Gene mapping describes the methods used to identify the locus of a gene and the distances between genes. Gene mapping can also describe the distances between different sites within a gene.

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids. It is widely used by cells to accurately repair harmful breaks that occur on both strands of DNA, known as double-strand breaks (DSB), in a process called homologous recombinational repair (HRR). Homologous recombination also produces new combinations of DNA sequences during meiosis, the process by which eukaryotes make gamete cells, like sperm and egg cells in animals. These new combinations of DNA represent genetic variation in offspring, which in turn enables populations to adapt during the course of evolution. Homologous recombination is also used in horizontal gene transfer to exchange genetic material between different strains and species of bacteria and viruses.

In genetics, a three-point cross is used to determine the loci of three genes in an organism's genome.

Recombination hotspots are regions in a genome that exhibit elevated rates of recombination relative to a neutral expectation. The recombination rate within hotspots can be hundreds of times that of the surrounding region. Recombination hotspots result from higher DNA break formation in these regions, and apply to both mitotic and meiotic cells. This appellation can refer to recombination events resulting from the uneven distribution of programmed meiotic double-strand breaks.

In genetics, completelinkage is defined as the state in which two loci are so close together that alleles of these loci are virtually never separated by crossing over. The closer the physical location of two genes on the DNA, the less likely they are to be separated by a crossing-over event. In the case of male Drosophila there is complete absence of recombinant types due to absence of crossing over. This means that all of the genes that start out on a single chromosome, will end up on that same chromosome in their original configuration. In the absence of recombination, only parental phenotypes are expected.

In population genetics, the Hill–Robertson effect, or Hill–Robertson interference, is a phenomenon first identified by Bill Hill and Alan Robertson in 1966. It provides an explanation as to why there may be an evolutionary advantage to genetic recombination.

The tetrad is the four spores produced after meiosis of a yeast or other Ascomycota, Chlamydomonas or other alga, or a plant. After parent haploids mate, they produce diploids. Under appropriate environmental conditions, diploids sporulate and undergo meiosis. The meiotic products, spores, remain packaged in the parental cell body to produce the tetrad.

Host–parasite coevolution is a special case of coevolution, where a host and a parasite continually adapt to each other. This can create an evolutionary arms race between them. A more benign possibility is of an evolutionary trade-off between transmission and virulence in the parasite, as if it kills its host too quickly, the parasite will not be able to reproduce either. Another theory, the Red Queen hypothesis, proposes that since both host and parasite have to keep on evolving to keep up with each other, and since sexual reproduction continually creates new combinations of genes, parasitism favours sexual reproduction in the host.

A recombinant inbred strain or recombinant inbred line (RIL) is an organism with chromosomes that incorporate an essentially permanent set of recombination events between chromosomes inherited from two or more inbred strains. F1 and F2 generations are produced by intercrossing the inbred strains; pairs of the F2 progeny are then mated to establish inbred strains through long-term inbreeding.

Zygotic induction occurs when a bacterial cell carrying the silenced DNA of a bacterial virus in its chromosome transfers the viral DNA along with its own DNA to another bacterial cell lacking the virus, causing the recipient of the DNA to break open. In the donor cell, a repressor protein encoded by the prophage keeps the viral genes turned off so that virus is not produced. When DNA is transferred to the recipient cell by conjugation, the viral genes in the transferred DNA are immediately turned on because the recipient cell lacks the repressor. As a result, many virus are made in the recipient cell, and lysis eventually occurs to release the new virus.

Hybrizyme is a term coined to indicate novel or normally rare gene variants that are associated with hybrid zones, geographic areas where two related taxa meet, mate, and produce hybrid offspring. The hybrizyme phenomenon is widespread and these alleles occur commonly, if not in all hybrid zones. Initially considered to be caused by elevated rates of mutation in hybrids, the most probable hypothesis infers that they are the result of negative (purifying) selection. Namely, in the center of the hybrid zone, negative selection purges alleles against hybrid disadvantage. Stated differently, any allele that will decrease reproductive isolation is favored and any linked alleles also increase their frequency by genetic hitchhiking. If the linked alleles used to be rare variants in the parental taxa, they will become more common in the area where the hybrids are formed.

Crossover interference is the term used to refer to the non-random placement of crossovers with respect to each other during meiosis. The term is attributed to Hermann Joseph Muller, who observed that one crossover "interferes with the coincident occurrence of another crossing over in the same pair of chromosomes, and I have accordingly termed this phenomenon ‘interference’."