Jerzy (Georg) Daniel Schultz known also as Daniel Schultz the Younger was a prominent painter of the Baroque era, born and active in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He painted many Polish and Lithuanian nobles, members of the royal family, local Patricians, such as the astronomer Johannes Hevelius; animals, and hunts. His work can be found at the Wawel Castle State Art Collections, the National Museum in Warsaw, the Stockholm National Museum, the Hermitage Museum, and at the Gdańsk National Museum.

Saqqara, also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English, is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara contains numerous pyramids, including the Pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Tomb, and a number of mastaba tombs. Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km.

Mummy portraits or Fayum mummy portraits are a type of naturalistic painted portrait on wooden boards attached to upper class mummies from Roman Egypt. They belong to the tradition of panel painting, one of the most highly regarded forms of art in the Classical world. The Fayum portraits are the only large body of art from that tradition to have survived. They were formerly, and incorrectly, called Coptic portraits.

A coffin is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, either for burial or cremation.

Poland–Lithuania, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and also referred to as the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth or the First Polish Republic, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch in real union, who was both King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. It was one of the largest and most populous countries of 16th- to 17th-century Europe. At its largest territorial extent, in the early 17th century, the Commonwealth covered almost 1,000,000 km2 (400,000 sq mi) and as of 1618 sustained a multi-ethnic population of almost 12 million. Polish and Latin were the two co-official languages, and Catholicism served as the state religion.

Sarmatism was an ethno-cultural ideology within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was the dominant Baroque culture and ideology of the nobility that existed in times of the Renaissance to the 18th centuries. Together with the concept of "Golden Liberty", it formed a central aspect of the Commonwealth social elites’ culture and society. At its core was the unifying belief that the people of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth descended from the ancient Iranian Sarmatians, the legendary invaders of contemporary Polish lands in antiquity.

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

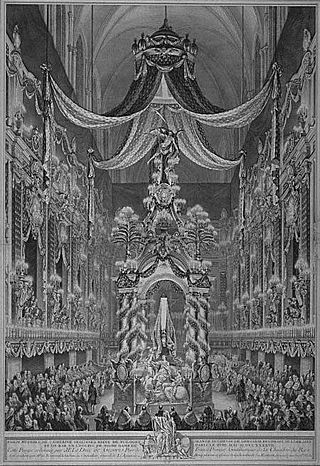

The castrum doloris was a structure and set of decorations which sheltered and accompanied the catafalque or bier in a funeral. It signified the prestige and power of the deceased, and was common in Poland-Lithuania and other parts of Europe.

A death mask is a likeness of a person's face after their death, usually made by taking a cast or impression from the corpse. Death masks may be mementos of the dead or be used for creation of portraits.

The Wawel Royal Castle and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established on the orders of King Casimir III the Great and enlarged over the centuries into a number of structures around an Italian-styled courtyard. It represents nearly all European architectural styles of the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods.

The Polish Baroque lasted from the early 17th to the mid-18th century. As with Baroque style elsewhere in Europe, Poland's Baroque emphasized the richness and triumphant power of contemporary art forms. In contrast to the previous, Renaissance style which sought to depict the beauty and harmony of nature, Baroque artists strove to create their own vision of the world. The result was manifold, regarded by some critics as grand and dramatic, but sometimes also chaotic and disharmonious and tinged with affectation and religious exaltation, thus reflecting the turbulent times of the 17th-century Europe.

The Royal Gniezno Cathedral is a Brick Gothic cathedral located in the historic city of Gniezno that served as the coronation place for several Polish monarchs and as the seat of Polish church officials continuously for nearly 1000 years. Throughout its long and tragic history, the building stayed mostly intact, making it one of the oldest and most precious sacral monuments in Poland.

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs, tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of ancestor veneration or as a publicly directed dynastic display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the lives of the living.

Equestrian Portrait of Count Stanislas Potocki is an oil painting on canvas completed by the French Neo-Classical painter Jacques-Louis David in 1781. A large-scale equestrian portrait, the work depicts a Polish politician, nobleman, and writer of the Enlightenment Period, Stanisław Kostka Potocki. The artist shows Potocki on horseback and wearing the sash of the Polish Order of the White Eagle. As Potocki tips his hat in a welcoming gesture to the viewer, the horse bows, while a dog can be seen barking in the lower left-hand corner of the painting.

St. Hyacinth's Church, named after Saint Hyacinth of Poland, is a Baroque Catholic church building located in Warsaw's New Town at Freta Street 8/10.

Mannerist architecture and sculpture in Poland dominated between 1550 and 1650, when it was finally replaced with baroque. The style includes various mannerist traditions, which are closely related with ethnic and religious diversity of the country, as well as with its economic and political situation at that time. The mannerist complex of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska and mannerist City of Zamość are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648) covers a period in the history of Poland and Lithuania, before their joint state was subjected to devastating wars in the mid-17th century. The Union of Lublin of 1569 established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a more closely unified federal state, replacing the previously existing personal union of the two countries. The Union was largely run by the Polish and increasingly Polonized Lithuanian and Ruthenian nobility, through the system of the central parliament and local assemblies, but from 1573 led by elected kings. The formal rule of the nobility, which was a much greater proportion of the population than in other European countries, constituted a sophisticated early democratic system, in contrast to the absolute monarchies prevalent at that time in the rest of Europe.[a]

The Oświęcim Chapel, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Stanislaus of Szczepanów, is an extension to the Gothic Franciscan Church in Krosno, Poland. Founded in 1647–1648 by a prominent representative of the Oświęcim family, it is also commonly known as the "Chapel of Love". Associated with the romantic legend of Stanisław Oświęcim's love for his sister Anna, the building is one of the finest artistic achievements of its era. It represents a type of early Baroque burial chapel built on a square plan, with a dome topped by a lantern inspired by the early Renaissance Sigismund's Chapel.

Portrait of Barbara Lubomirska is a 17th-century funerary portrait of the Polish noblewoman Barbara Lubomirska. She died between 1667 and 1676 and the portrait is shaped like a cross-section of her coffin. It was painted in oil on a sheet of metal by an anonymous master-painter active in Masovia in mid-second half of the 17th century. The painting is on display at the National Museum in Warsaw on loan from the Portrait Gallery of the Palace Museum in Wilanów. It is a prominent example of the funerary art tradition popular among the nobles (szlachta) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

![Coffin portrait of Jan Gniewosz, c. 1700, oil on tin plate.

Signature: I.[an] G.[niewosz] N.[a] O.[oleksowie] K.[asztelan] C.[zchowski]

English: Jan Gniewosz [lord] of Oleksow, castellan of Czchow Coffin portrait of Jan Gniewosz.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Coffin_portrait_of_Jan_Gniewosz.jpg/300px-Coffin_portrait_of_Jan_Gniewosz.jpg)