Mary Ann Shadd Cary was an American-Canadian anti-slavery activist, journalist, publisher, teacher, and lawyer. She was the first Black woman publisher in North America and the first woman publisher in Canada. Shadd Cary edited The Provincial Freeman, established in 1853. Published weekly in Ontario, it advocated equality, integration and self-education for black people in Canada and the United States.

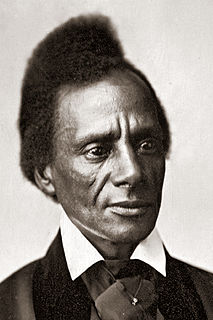

Charles Lenox Remond was an American orator, activist and abolitionist based in Massachusetts. He lectured against slavery across the Northeast, and in 1840 traveled to the British Isles on a tour with William Lloyd Garrison. During the American Civil War, he recruited blacks for the United States Colored Troops, helping staff the first two units sent from Massachusetts. From a large family of African-American entrepreneurs, he was the brother of Sarah Parker Remond, also a lecturer against slavery.

The Founding Fathers of the United States, or simply the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of American leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, led the war for independence from Great Britain, and built a frame of government for the new United States of America upon republican principles during the latter decades of the 18th century.

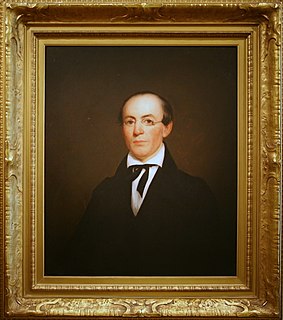

William Whipper was an African-American abolitionist. Whipper was a successful businessman who played a key role in the antislavery movement as a reformer. He advocated nonviolence and co-founded the American Moral Reform Society, an early African-American abolitionist organization. William Whipper epitomized the unique prosperity that Northern Blacks were able to attain in the mid-19th century.

Lewis Hayden was an African-American leader who escaped with his family from slavery in Kentucky; they moved as refugees to Boston, Massachusetts. There he became an abolitionist, lecturer, businessman, and politician. Before the American Civil War, he and his wife Harriet Hayden aided numerous fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, often sheltering them at their house.

The first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women was held on May 9–12, 1837. One hundred and seventy-five women, from ten different states and representing twenty female antislavery groups, gathered in New York City to discuss their role in the American abolition movement. This gathering represented the first time that women from such a broad geographic area met with the common purpose of promoting the anti-slavery cause among women. Mary S. Parker was the President of the gathering. Other prominent women went on to be vocal members of the Women's Suffrage Movement, including Lucretia Mott, the Grimké sisters, and Lydia Maria Child. The attendees included women of color, the wives and daughters of slaveholders, and women of low economic status.

William Cooper Nell was an African-American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Writing for abolitionist newspapers The Liberator and The North Star, he helped publicize the anti-slavery cause. He published the North Star from 1847 to 18xx, moving temporarily to Rochester, New York.

The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, headquartered in Boston, was organized as an auxiliary of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1835. Its roots were in the New England Anti-Slavery Society, organized by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator, in 1831, after the defeat of a proposal for a college for blacks in New Haven.

Lucretia Mott was a U.S. Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongst the women excluded from the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840. In 1848 she was invited by Jane Hunt to a meeting that led to the first meeting about women's rights. Mott helped write the Declaration of Sentiments during the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.

African-American women began to agitate for political rights in the 1830s, creating the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and New York Female Anti-Slavery Society. These interracial groups were radical expressions of women's political ideals, and they led directly to voting rights activism before and after the Civil War. Throughout the 19th century, African-American women like Harriet Forten Purvis, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper worked on two fronts simultaneously: reminding African-American men and white women that Black women needed legal rights, especially the right to vote.

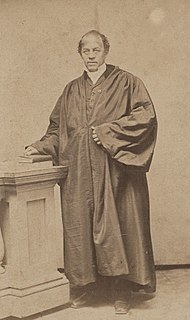

Leonard Andrew Grimes was an African-American abolitionist and pastor. He served as a conductor of the Underground Railroad, including his efforts to free fugitive slave Anthony Burns captured in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. After the Civil War began, Grimes petitioned for African-American enlistment. He then recruited soldiers for the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

Primus Hall was born a slave. He was the son of Prince Hall, an abolitionist, Revolutionary War soldier and founder of the Prince Hall Freemasonry.

John Telemachus Hilton was an African-American abolitionist who established barber, furniture dealer and employment agency businesses. He was a Prince Hall Mason and established the Prince Hall National Grand Lodge of North America and served as its first National Grand Master for ten years. He also was a founding member of the Massachusetts General Colored Association, and active member and author in the Anti-Slavery movement.

Abolitionism in the United States was the movement that sought to end slavery in the United States, and was active both before and during the American Civil War. In the Americas and Western Europe, abolitionism was a movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and to free the slaves. In the 18th century, Enlightenment thinkers condemned slavery on humanistic grounds and English Quakers and some Evangelical denominations condemned slavery as un-Christian. At that time, most slaves were Africans, but thousands of Native Americans were also enslaved. In the 18th century, as many as six million Africans were transported to the Americas as slaves, at least a third of them on British ships to North America. The Colony of Georgia originally prohibited slavery.

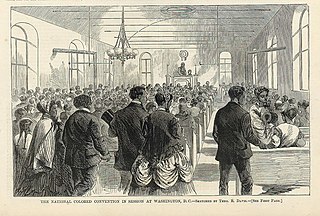

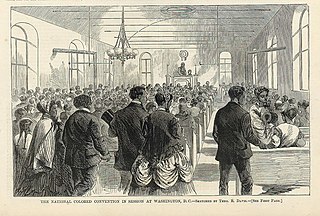

The Colored Conventions Movement, or Negro Convention Movement, was a series of national, regional, and state conventions held irregularly during the decades preceding and following the American Civil War. The delegates who attended these conventions consisted of both free and fugitive African Americans including religious leaders, businessmen, politicians, writers, publishers, and abolitionists. The conventions provided "an organizational structure through which black men could maintain a distinct black leadership and pursue black abolitionist goals." The minutes from these conventions show that Antebellum African-Americans sought justice beyond the emancipation of their enslaved countrymen: they also organized to discuss issues concerning labor, healthcare, temperance and educational equality. Although the conventions largely subsided following the Civil War, the Colored Conventions of antebellum America are seen as the precursors to larger African American organizations, including the Colored National Labor Union, the Niagara Movement, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Harriet Forten Purvis was an African-American abolitionist and first generation suffragist. With her mother and sisters, she formed the first biracial women's abolitionist group, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. She hosted anti-slavery events at her home and with her husband Robert Purvis ran an Underground Railroad station. Robert and Harriet also founded the Gilbert Lyceum. She fought against segregation and for the right for blacks to vote after the Civil War.

Amy Hester "Hetty" Reckless was a runaway slave who became part of the American abolitionist movement. She campaigned against slavery and was part of the Underground Railroad, operating a Philadelphia safe house. She fought against prostitution and vice, working toward improving education and skills for the black community. Through efforts including operating a women's shelter, supporting Sunday Schools and attending conferences, she became a leader in the abolitionist community. After her former master's death, she returned to New Jersey and continued working to assist escaping slaves throughout the Civil War.

Sattira 'Sattie' Douglas was an African American abolitionist from the nineteenth century who helped organize multiple confederations in helping African Americans in Chicago and the West. Douglas traveled to Kansas near the end of the Civil War, where she took up teaching contrabands.

Abraham Doras Shadd (1801–1882), was a free African-American abolitionist and civil rights activist who emigrated to Ontario, Canada, and would later become one of Canada's first black elected officials. He was also the father of prominent activist and publisher Mary Ann Shadd.

The Colored Women's Progressive Franchise was an organization advocating for equal rights of African American women organized by Mary Ann Shadd Cary in 1880. Also referred to as the Colored Women's Progressive Franchise Association or the Colored Women's Progressive Association, the organization paved the path for a movement of Black women's organizations and institutions that articulated feminist concerns and agendas, which followed the end of Reconstruction. Among the features of the significance of the Colored Women's Progressive Franchise is that it preceded the women's club movement in Washington, D.C. by more than a decade. It is speculated that this historical precocity as well as Shadd Cary's confrontational style are among the reasons that the organization did not last for very long.