A color code is a system for encoding and representing non-color information with colors to facilitate communication. This information tends to be categorical though may also be sequential.

Musical notation is any system used to visually represent auditorily perceived music, played with instruments or sung by the human voice through the use of symbols, including notation for durations of absence of sound such as rests. For this reason, the act of deciphering or reading a piece using musical notation, is known as "reading music".

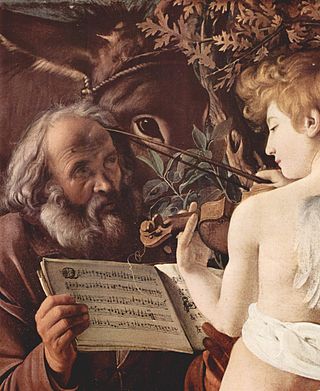

Sheet music is a handwritten or printed form of musical notation that uses musical symbols to indicate the pitches, rhythms, or chords of a song or instrumental musical piece. Like its analogs – printed books or pamphlets in English, Arabic, or other languages – the medium of sheet music typically is paper. However, access to musical notation since the 1980s has included the presentation of musical notation on computer screens and the development of scorewriter computer programs that can notate a song or piece electronically, and, in some cases, "play back" the notated music using a synthesizer or virtual instruments.

In music, sight-reading, also called a prima vista, is the practice of reading and performing of a piece in a music notation that the performer has not seen or learned before. Sight-singing is used to describe a singer who is sight-reading. Both activities require the musician to play or sing the notated rhythms and pitches.

Graphic notation is the representation of music through the use of visual symbols outside the realm of traditional music notation. Graphic notation became popular in the 1950s, and can be used either in combination with or instead of traditional music notation. Graphic notation was influenced by contemporary visual art trends in its conception, bringing stylistic components from modern art into music. Composers often rely on graphic notation in experimental music, where standard musical notation can be ineffective. Other uses include pieces where an aleatoric or undetermined effect is desired. One of the earliest pioneers of this technique was Earle Brown, who, along with John Cage, sought to liberate performers from the constraints of notation and make them active participants in the creation of the music.

Braille music is a braille code that allows music to be notated using braille cells so music can be read by visually impaired musicians. The system was incepted by Louis Braille.

The clavier à lumières, or tastiera per luce, as it appears in the score, was a musical instrument invented by Alexander Scriabin for use in his work Prometheus: Poem of Fire. Only one version of this instrument was constructed, for the performance of Prometheus: Poem of Fire in New York City in 1915. The instrument was supposed to be a keyboard, with notes corresponding to colors as given by Scriabin's synesthetic system, specified in the score. However, numerous synesthesia researchers have cast doubt on the claim that Scriabin was a synesthete.

In psychology, the Stroop effect is the delay in reaction time between congruent and incongruent stimuli.

A classroom, schoolroom or lecture room is a learning space in which both children and adults learn. Classrooms are found in educational institutions of all kinds, ranging from preschools to universities, and may also be found in other places where education or training is provided, such as corporations and religious and humanitarian organizations. The classroom provides a space where learning can take place uninterrupted by outside distractions.

Mensural notation is the musical notation system used for polyphonic European vocal music from the late 13th century until the early 17th century. The term "mensural" refers to the ability of this system to describe precisely measured rhythmic durations in terms of numerical proportions between note values. Its modern name is inspired by the terminology of medieval theorists, who used terms like musica mensurata or cantus mensurabilis to refer to the rhythmically defined polyphonic music of their age, as opposed to musica plana or musica choralis, i.e., Gregorian plainchant. Mensural notation was employed principally for compositions in the tradition of vocal polyphony, whereas plainchant retained its own, older system of neume notation throughout the period. Besides these, some purely instrumental music could be written in various forms of instrument-specific tablature notation.

The Kodály method, also referred to as the Kodály concept, is an approach to music education developed in Hungary during the mid-twentieth century by Zoltán Kodály. His philosophy of education served as inspiration for the method, which was then developed over a number of years by his associates. In 2016, the method was inscribed as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Eye movement in music reading is the scanning of a musical score by a musician's eyes. This usually occurs as the music is read during performance, although musicians sometimes scan music silently to study it. The phenomenon has been studied by researchers from a range of backgrounds, including cognitive psychology and music education. These studies have typically reflected a curiosity among performing musicians about a central process in their craft, and a hope that investigating eye movement might help in the development of more effective methods of training musicians' sight reading skills.

In music, a notehead is the part of a note, usually elliptical in shape, whose placement on the staff indicates the pitch, to which modifications are made that indicate duration. Noteheads may be the same shape but colored completely black or white, indicating the note value. In a whole note, the notehead, shaped differently than shorter notes, is the only component of the note. Shorter note values attach a stem to the notehead, and possibly beams or flags. The longer double whole note can be written with vertical lines surrounding it, two attached noteheads, or a rectangular notehead. An "x" shaped notehead may be used to indicate percussion, percussive effects, or speaking. A square, diamond, or box shaped notehead may be used to indicate a natural or artificial harmonic. A small notehead can be used to indicate a grace note.

Simplified music notation is an alternative form of music notation designed to make sight-reading easier. It was proposed by Peter Hayes George (1927–2012). It is based on classical staff notation, but sharps and flats are incorporated into the shape of the note heads. Notes such as double sharps and double flats are written at the pitch at which they are actually played, but preceded by symbols called "history signs" to show that they have been transposed. The key signature and all other information in the original score is retained, but the player does not need to remember the key signature and accidentals while playing.

Piano pedagogy is the study of the teaching of piano playing. Whereas the professional field of music education pertains to the teaching of music in school classrooms or group settings, piano pedagogy focuses on the teaching of musical skills to individual piano students. This is often done via private or semiprivate instructions, commonly referred to as piano lessons. The practitioners of piano pedagogy are called piano pedagogues, or simply, piano teachers.

Rapid automatized naming (RAN) is a task that measures how quickly individuals can name aloud objects, pictures, colors, or symbols. Variations in rapid automatized naming time in children provide a strong predictor of their later ability to read, and is independent from other predictors such as phonological awareness, verbal IQ, and existing reading skills. Importantly, rapid automatized naming of pictures and letters can predict later reading abilities for pre-literate children.

Dalcroze eurhythmics, also known as the Dalcroze method or simply eurhythmics, is one of several developmental approaches including the Kodály method, Orff Schulwerk and Suzuki Method used to teach music to students. Eurhythmics was developed in the early 20th century by Swiss musician and educator Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. Dalcroze eurhythmics teaches concepts of rhythm, structure, and musical expression using movement, and is the concept for which Dalcroze is best known. It focuses on allowing the student to gain physical awareness and experience of music through training that takes place through all of the senses, particularly kinesthetic.

The Silent Way is a language-teaching approach created by Caleb Gattegno that makes extensive use of silence as a teaching method. Gattegno introduced the method in 1963, in his book Teaching Foreign Languages in Schools: The Silent Way. Gattegno was critical of mainstream language education at the time, and he based the method on his general theories of education rather than on existing language pedagogy. It is usually regarded as an "alternative" language-teaching method; Cook groups it under "other styles", Richards groups it under "alternative approaches and methods" and Jin & Cortazzi group it under "Humanistic or Alternative Approaches".

Takadimi is a system devised by Richard Hoffman, William Pelto, and John W. White in 1996 in order to teach rhythm skills. Takadimi, while utilizing rhythmic symbols borrowed from classical South Indian carnatic music, differentiates itself from this method by focusing the syllables on meter and western tonal rhythm. Takadimi is based on the use of specific syllables at certain places within a beat. Takadimi is used in classrooms from elementary level up through the collegiate level. It meets National Content Standard 5 by teaching both reading and notating music.

Musical literacy is the reading, writing, and playing of music, as well an understanding of cultural practice and historical and social contexts.