Related Research Articles

Poaching is the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights. Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set against the hunting privileges of nobility and territorial rulers.

A game reserve is a large area of land where wild animals live safely or are hunted in a controlled way for sport. If hunting is prohibited, a game reserve may be considered a nature reserve; however, the focus of a game reserve is specifically the animals (fauna), whereas a nature reserve is also, if not equally, concerned with all aspects of native biota of the area.

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (Zimparks) is an agency of the Zimbabwe government managing national parks. Zimbabwe's game reserves are managed by the government. They were initially founded as a means of using unproductive land.

Trophy hunting is a form of hunting for sport in which parts of the hunted wild animals are kept and displayed as trophies. The animal being targeted, known as the "game", is typically a mature male specimen from a popular species of collectable interests, usually of large sizes, holding impressive horns, antlers, furs or manes. Most trophies consist of only select parts of the animal, which are prepared for display by a taxidermist. The parts most commonly kept vary by species, but often include head, hide, tusks, horns, or antlers.

Liwonde National Park, also known as Liwonde Wildlife Reserve, is a national park in southern Malawi, near the Mozambique border. The park was established in 1973, and has been managed by the nonprofit conservation organization African Parks since August 2015. African Parks built an electric fence around the perimeter of the park to help mitigate human-wildlife conflict. In early 2018, the adjacent Mangochi Forest Reserve was also brought under African Parks' management, almost doubling the size of the protected area.

A game farm is a place where game animals are raised to stock wildlife areas for hunting. The term also includes places where such animals are raised to be sold as food or for photography. Their existence has been exemplified within the South African countryside where they have become prevalent. The wildlife that is hunted is used for consumption as well for ecotourism. Local laws in South Africa during the 20th century have allowed the private ownership of wildlife, which has enabled the expansion and economic feasibility of game farms over typical livestock farming.

Environmental issues in Kenya include deforestation, soil erosion, desertification, water shortage and degraded water quality, flooding, poaching, and domestic and industrial pollution.

Size of Wales is a climate change charity founded with the aim of conserving an area of tropical rainforest the size of Wales. The project currently supports seven forest protection projects and one tree planting project across Africa and South America. The charity focuses upon furthering the promotion of rainforest conservation as a national response to the global issue of climate change.

Wildlife tourism is an element of many nations' travel industry centered around observation and interaction with local animal and plant life in their natural habitats. While it can include eco- and animal-friendly tourism, safari hunting and similar high-intervention activities also fall under the umbrella of wildlife tourism. Wildlife tourism, in its simplest sense, is interacting with wild animals in their natural habitat, either by actively or passively. Wildlife tourism is an important part of the tourism industries in many countries including many African and South American countries, Australia, India, Canada, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Maldives among many. It has experienced a dramatic and rapid growth in recent years worldwide and many elements are closely aligned to eco-tourism and sustainable tourism.

The wildlife of Zimbabwe occurs foremost in remote or rugged terrain, in national parks and private wildlife ranches, in miombo woodlands and thorny acacia or kopje. The prominent wild fauna includes African buffalo, African bush elephant, black rhinoceros, southern giraffe, African leopard, lion, plains zebra, and several antelope species.

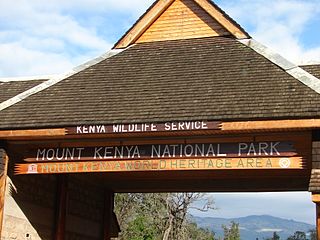

Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) is a state corporation under the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife established by an act of Parliament; Wildlife Conservation and Management Act CAP 376, of 1989, now repealed and replaced by the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act, 2013. At independence, the Government of Kenya committed itself to conserving wildlife for posterity with all the means at its disposal, including the places animals lived, forests and water catchment areas.

Namibia is one of few countries in the world to specifically address habitat conservation and protection of natural resources in their constitution. Article 95 states, "The State shall actively promote and maintain the welfare of the people by adopting international policies aimed at the following: maintenance of ecosystems, essential ecological processes, and biological diversity of Namibia, and utilization of living natural resources on a sustainable basis for the benefit of all Namibians, both present and future.".

Wildlife Alliance is an international non-profit forest and wildlife conservation organization with current programs in Cambodia. It is headquartered in New York City, with offices in Phnom Penh. The logo of the organization is the Asian elephant, an emblematic species and the namesake for the Southwest Elephant Corridor that Wildlife Alliance saved when it was under intense threat of poaching and habitat destruction in 2001. It is today one of the last remaining unfragmented elephant corridors in Asia. Due to Government rangers' and Wildlife Alliance's intensive anti-poaching efforts, there have been zero elephant killings since 2006. Dr. Suwanna Gauntlett is the Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Wildlife Alliance, and one of the original founders of WildAid. The organization is governed by a board of directors and an international advisory board that provides guidance on strategy, fundraising, and outreach.

The ivory trade is the commercial, often illegal trade in the ivory tusks of the hippopotamus, walrus, narwhal, black and white rhinos, mammoth, and most commonly, African and Asian elephants.

The Okomu National Park, formerly the Okomu Wildlife Sanctuary, has been identified as one of the largest remaining natural rainforest ecosystem. Due to the high biodiversity seen in the Okomu National Park, a Wildlife Sanctuary was first established there.

Margaret Jacobsohn is a Namibian environmentalist. She was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 1993, jointly with Garth Owen-Smith, for their efforts on conservation of wildlife in rural Namibia.

Elephant hunting, which used to be an accepted activity in Kenya, was banned in 1973, as was the ivory trade. Poaching continues, as there is still international demand for elephant tusks. Kenya pioneered the destruction of ivory as a way to combat this black market. Elephant poaching continues to pose a threat to the population.

Mudumu is a National Park in Caprivi Region in north-eastern Namibia. The park was established in 1990. It covers an area of 737 square kilometres (285 sq mi). The Kwando River forms the western border with Botswana. Various communal area conservancies and community forests surround Mudumu National Park.

Hemmersbach Rhino Force is a direct action conservation organization acting with a focus on the African rhinos. Rhino Force's main activities consist of anti-poaching rangers in the Greater Kruger National Park, a biobank called Hemmersbach Rhino Force Cryovault to preserve rhino genes and the Black Rhino Reintroduction to bring back rhinos to the Mid Zambezi Valley in Zimbabwe.

References

- Satchell, Michael (1996-11-25). "Save the elephants: Start shooting them". U.S. News & World Report. p. 51. ISSN 0041-5537.

- Fortmann, Louise (2005). "What We Need is a Community Bambi: The Perils and Possibilities of Powerful Symbols" (PDF). In J. Peter Brosius; Charles Zerner; Anna Lowenhaupt (eds.). Communities and Conservation: Histories and Politics of Community-Based Natural Resource Management. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira. pp. 195–205.

- Vorlaufer, Karl (2002-04-01). "CAMPFIRE — The Political Ecology of Poverty Alleviation, Wildlife Utilisation and Biodiversity Conservation in Zimbabwe (CAMPFIRE — Die Politische Ökologie der Armutsbekämpfung, Wildtiernutzung und des Biodiversitäts-schutzes in Zimbabwe)". Erdkunde . 56 (2): 184–206. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.2002.02.06. ISSN 0014-0015. JSTOR 25647452.

- Press, Robert (1993-06-22). "Wildlife Protection Gets a Tough Probe". Christian Science Monitor. p. 13. ISSN 0882-7729 . Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- Schouten, Fredreka (2000-01-20). "African trip draws criticism". USA Today (FINAL ed.). ISSN 0734-7456 . Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- Rowe, Peter (1997-05-08). "Stampeding toward ivory and irony". San Diego Union-Tribune (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 ed.). pp. E-1. ISSN 1063-102X . Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- Archabald, Karen; Lisa Naughton-Treves (2001). "Tourism revenue-sharing around national parks in Western Uganda: early efforts to identify and reward local communities". Environmental Conservation. 28 (2): 135–149. doi:10.1017/S0376892901000145. S2CID 85748166.