In economics, utility is a measure of a certain person's satisfaction from a certain state of the world. Over time, the term has been used with at least two meanings.

In economics, an indifference curve connects points on a graph representing different quantities of two goods, points between which a consumer is indifferent. That is, any combinations of two products indicated by the curve will provide the consumer with equal levels of utility, and the consumer has no preference for one combination or bundle of goods over a different combination on the same curve. One can also refer to each point on the indifference curve as rendering the same level of utility (satisfaction) for the consumer. In other words, an indifference curve is the locus of various points showing different combinations of two goods providing equal utility to the consumer. Utility is then a device to represent preferences rather than something from which preferences come. The main use of indifference curves is in the representation of potentially observable demand patterns for individual consumers over commodity bundles.

Marginalism is a theory of economics that attempts to explain the discrepancy in the value of goods and services by reference to their secondary, or marginal, utility. It states that the reason why the price of diamonds is higher than that of water, for example, owes to the greater additional satisfaction of the diamonds over the water. Thus, while the water has greater total utility, the diamond has greater marginal utility.

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption, by maximizing utility subject to a consumer budget constraint. Factors influencing consumers' evaluation of the utility of goods include: income level, cultural factors, product information and physio-psychological factors.

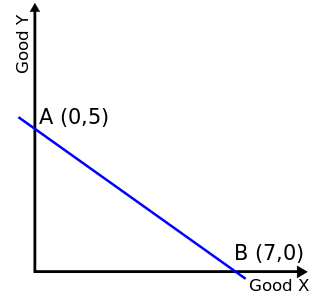

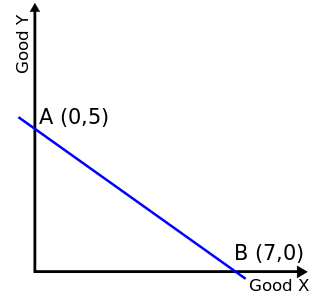

In economics, a budget constraint represents all the combinations of goods and services that a consumer may purchase given current prices within their given income. Consumer theory uses the concepts of a budget constraint and a preference map as tools to examine the parameters of consumer choices. Both concepts have a ready graphical representation in the two-good case. The consumer can only purchase as much as their income will allow, hence they are constrained by their budget. The equation of a budget constraint is where is the price of good X, and is the price of good Y, and m is income.

In economics, the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) is the rate at which a consumer can give up some amount of one good in exchange for another good while maintaining the same level of utility. At equilibrium consumption levels, marginal rates of substitution are identical. The marginal rate of substitution is one of the three factors from marginal productivity, the others being marginal rates of transformation and marginal productivity of a factor.

In microeconomics, the contract curve or Pareto set is the set of points representing final allocations of two goods between two people that could occur as a result of mutually beneficial trading between those people given their initial allocations of the goods. All the points on this locus are Pareto efficient allocations, meaning that from any one of these points there is no reallocation that could make one of the people more satisfied with his or her allocation without making the other person less satisfied. The contract curve is the subset of the Pareto efficient points that could be reached by trading from the people's initial holdings of the two goods. It is drawn in the Edgeworth box diagram shown here, in which each person's allocation is measured vertically for one good and horizontally for the other good from that person's origin ; one person's origin is the lower left corner of the Edgeworth box, and the other person's origin is the upper right corner of the box. The people's initial endowments are represented by a point in the diagram; the two people will trade goods with each other until no further mutually beneficial trades are possible. The set of points that it is conceptually possible for them to stop at are the points on the contract curve.

Utility maximization was first developed by utilitarian philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. In microeconomics, the utility maximization problem is the problem consumers face: "How should I spend my money in order to maximize my utility?" It is a type of optimal decision problem. It consists of choosing how much of each available good or service to consume, taking into account a constraint on total spending (income), the prices of the goods and their preferences.

In economics, an ordinal utility function is a function representing the preferences of an agent on an ordinal scale. Ordinal utility theory claims that it is only meaningful to ask which option is better than the other, but it is meaningless to ask how much better it is or how good it is. All of the theory of consumer decision-making under conditions of certainty can be, and typically is, expressed in terms of ordinal utility.

There are two fundamental theorems of welfare economics. The first states that in economic equilibrium, a set of complete markets, with complete information, and in perfect competition, will be Pareto optimal. The requirements for perfect competition are these:

- There are no externalities and each actor has perfect information.

- Firms and consumers take prices as given.

In microeconomics, a consumer's Hicksian demand function or compensated demand function for a good is their quantity demanded as part of the solution to minimizing their expenditure on all goods while delivering a fixed level of utility. Essentially, a Hicksian demand function shows how an economic agent would react to the change in the price of a good, if the agent's income was compensated to guarantee the agent the same utility previous to the change in the price of the good—the agent will remain on the same indifference curve before and after the change in the price of the good. The function is named after John Hicks.

The Samuelson condition, due to Paul Samuelson, in the theory of public economics, is a condition for optimal provision of public goods.

Gorman polar form is a functional form for indirect utility functions in economics.

Stochastic dominance is a partial order between random variables. It is a form of stochastic ordering. The concept arises in decision theory and decision analysis in situations where one gamble can be ranked as superior to another gamble for a broad class of decision-makers. It is based on shared preferences regarding sets of possible outcomes and their associated probabilities. Only limited knowledge of preferences is required for determining dominance. Risk aversion is a factor only in second order stochastic dominance.

In economics, convex preferences are an individual's ordering of various outcomes, typically with regard to the amounts of various goods consumed, with the property that, roughly speaking, "averages are better than the extremes". The concept roughly corresponds to the concept of diminishing marginal utility without requiring utility functions.

Competitive equilibrium is a concept of economic equilibrium, introduced by Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu in 1951, appropriate for the analysis of commodity markets with flexible prices and many traders, and serving as the benchmark of efficiency in economic analysis. It relies crucially on the assumption of a competitive environment where each trader decides upon a quantity that is so small compared to the total quantity traded in the market that their individual transactions have no influence on the prices. Competitive markets are an ideal standard by which other market structures are evaluated.

Benders decomposition is a technique in mathematical programming that allows the solution of very large linear programming problems that have a special block structure. This block structure often occurs in applications such as stochastic programming as the uncertainty is usually represented with scenarios. The technique is named after Jacques F. Benders.

In economics, and in other social sciences, preference refers to an order by which an agent, while in search of an "optimal choice", ranks alternatives based on their respective utility. Preferences are evaluations that concern matters of value, in relation to practical reasoning. Individual preferences are determined by taste, need, ..., as opposed to price, availability or personal income. Classical economics assumes that people act in their best (rational) interest. In this context, rationality would dictate that, when given a choice, an individual will select an option that maximizes their self-interest. But preferences are not always transitive, both because real humans are far from always being rational and because in some situations preferences can form cycles, in which case there exists no well-defined optimal choice. An example of this is Efron dice.

Several theories of taxation exist in public economics. Governments at all levels need to raise revenue from a variety of sources to finance public-sector expenditures.

In operations research and social choice, the proportional-fair (PF) rule is a rule saying that, among all possible alternatives, one should pick an alternative that cannot be improved, where "improvement" is measured by the sum of relative improvements possible for each individual agent. It aims to provide a compromise between the utilitarian rule - which emphasizes overall system efficiency, and the egalitarian rule - which emphasizes individual fairness.