Related Research Articles

Dorothy Irene Height was an African-American civil rights and women's rights activist. She focused on the issues of African-American women, including unemployment, illiteracy, and voter awareness. Height is credited as the first leader in the civil rights movement to recognize inequality for women and African Americans as problems that should be considered as a whole. She was the president of the National Council of Negro Women for 40 years. Height's role in the "Big Six" civil rights movement was frequently ignored by the press due to sexism. In 1974, she was named to the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, which published the Belmont Report, a bioethics report in response to the infamous "Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

Abiel Smith School, founded in 1835, is a school located at 46 Joy Street in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, adjacent to the African Meeting House. It is named for Abiel Smith, a white philanthropist who left money in his will to the city of Boston for the education of black children.

The Moorland–Spingarn Research Center (MSRC) in Washington, D.C., is located on the campus of Howard University on the first and ground floors of Founders Library. The MSRC is recognized as one of the world's largest and most comprehensive repositories for the documentation of the history and culture of people of African descent in Africa, the Americas, and other parts of the world. As one of Howard University's major research facilities, the MSRC collects, preserves, organizes and makes available for research a wide range of resources chronicling the Black experience. Thus, it maintains a tradition of service which dates to the formative years of Howard University, when materials related to Africa and African Americans were first acquired.

The Broward County Library is a public library system in Broward County, Florida, in the United States. The system contains 37 branch locations and circulates over 9 million items annually. The system includes the Main Library in Fort Lauderdale, five regional libraries, and various branches.

Dorothy Louise Porter Wesley was a librarian, bibliographer and curator, who built the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University into a world-class research collection. She was the first African American to receive a library science degree from Columbia University. Porter published numerous bibliographies on African American history. When she realized that the Dewey Decimal System had only two classification numbers for African Americans, one for slavery and one for colonization, she created a new classification system that ordered books by genre and author.

Niara Sudarkasa was an American scholar, educator, Africanist and anthropologist who holds thirteen honorary degrees, and is the recipient of nearly 100 civic and professional awards. In 1989 Essence magazine named her "Educator for the '90s", and in 2001 she became the first African American to be installed as a Chief in the historic Ife Kingdom of the Yoruba of Nigeria.

Mayme Agnew Clayton was a librarian, and the founder, president, and leader of the Western States Black Research and Education Center (WSBREC), the largest privately held collection of African-American historical materials in the world. The collection represents the core holdings of the Mayme A. Clayton Library and Museum (MCLM), formerly located in Culver City, California. This collection was curated and managed by her son, Avery Clayton. The museum is the largest and most academically substantial independently held collection of objects, documents, and memorabilia on African American history and culture. On July 31, 2019, the Mayme A. Clayton Library and Museum closed permanently. The bulk of its collections went to the West Los Angeles College in unincorporated Los Angeles County on a temporary basis.

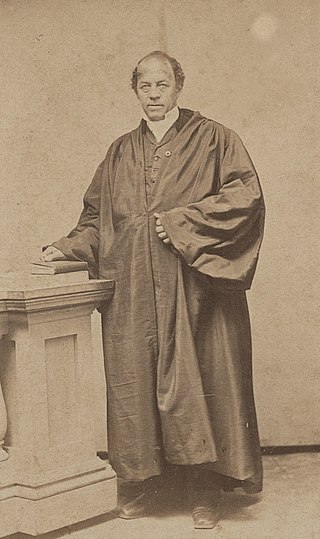

William Cooper Nell was an American abolitionist, journalist, publisher, author, and civil servant of Boston, Massachusetts, who worked for the integration of schools and public facilities in the state. Writing for abolitionist newspapers The Liberator and The North Star, he helped publicize the anti-slavery cause. He published the North Star from 1847 to 1851, moving temporarily to Rochester, New York.

Virginia Lacy Jones was an American librarian who throughout her 50-year career in the field pushed for the integration of public and academic libraries. She was one of the first African Americans to earn a PhD in Library Science and became dean of Atlanta University's School of Library Sciences.

Hosea Easton (1798–1837) was an American Congregationalist and Methodist minister, abolitionist activist, and author. He was one of the leaders of the convention movement in New England.

Leonard Andrew Grimes was an African-American abolitionist and pastor. He served as a conductor of the Underground Railroad, including his efforts to free fugitive slave Anthony Burns captured in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. After the Civil War began, Grimes petitioned for African-American enlistment. He then recruited soldiers for the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

Jean Blackwell Hutson was an American librarian, archivist, writer, curator, educator, and later chief of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The Schomburg Center dedicated their Research and Reference Division in honor of Hutson.

Miriam Matthews was an American librarian, advocate for intellectual freedom, historian, and art collector. In 1927, Matthews became the first credentialed African American librarian to be hired by the Los Angeles Public Library.

Florida Ruffin Ridley was an African-American civil rights activist, suffragist, teacher, writer, and editor from Boston, Massachusetts. She was one of the first black public schoolteachers in Boston, and edited The Woman's Era, the country's first newspaper published by and for African-American women.

Catherine Allen Latimer was the New York Public Library's first African-American librarian. She was a notable authority on bibliographies of African-American life and instrumental in forming the library's Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints.

The African-American Research Library and Cultural Center is a library located at 2650 Sistrunk Boulevard in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in the United States. A branch of the Broward County Library, it opened on October 26, 2002.

Joyce Annette Madkins Sumbi was an American librarian. She was the first African-American administrator in the LA County Library system.

Cosette Nell Kies was an American writer, librarian, and academic. She was a professor and occult researcher at Northern Illinois University where she served as chair of library and information services. Kies wrote on topics including public relations and marketing for libraries and horror fiction for young adults.

Carol June Bradley was an American music librarian.

The history of libraries for African Americans in the United States includes the earliest segregated libraries for African Americans that were school libraries. The fastest library growth happened in urban cities such as Atlanta while rural towns, particularly in the American South, were slower to add Black libraries. Andrew Carnegie and the Works Progress Administration helped establish libraries for African Americans, including at historically Black college and university campuses. Many public and private libraries were segregated until after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling of Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

References

- 1 2 3 Morand, Michael (February 13, 2020). "Black History Month Pop-Up Exhibit Celebrates Carter G. Woodson, Dorothy Porter Wesley, and Golden Legacy Magazine". Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Yale University Library. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- 1 2 "Constance Porter Uzelac papers, circa 1966-2011". Robert W. Woodruff Library, Emory University . Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ Weeks, Linton (November 15, 1995). "The Undimmed Light". The Washington Post . Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ "Labor of love: Daughter catalogs works". Miami Herald . February 2, 2003. Retrieved June 23, 2024– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Uzelac, Constance Porter". BlackPast.org . January 19, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Uzelac". South Florida Sun Sentinel . May 3, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2024– via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 George, Robert (March 7, 2000). "A Family's Legacy". South Florida Sun Sentinel . pp. 1E, 7E . Retrieved June 25, 2024– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Jacobs, Donald M. (2002). "Foreword". William Cooper Nell, Nineteenth-century African American Abolitionist, Historian, Integrationist. Black Classic Press. p. xxx-xxxii. ISBN 9781574780192.

- 1 2 Burch, Audra D.S. (August 25, 1999). "A Glimpse Of Black History". The Miami Herald . pp. 1A, 4A . Retrieved June 23, 2024– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Winter, Christine (November 30, 2003). "Internet growing more egalitarian". South Florida Sun Sentinel . Retrieved June 28, 2024– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Dickerson, Dennis C. (2019). The African Methodist Episcopal Church. p. 565. doi:10.1017/9781139017930.012. ISBN 978-0-521-19152-4 . Retrieved 17 June 2022.