Related Research Articles

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and then reaches the visual cortex. The area of the visual cortex that receives the sensory input from the lateral geniculate nucleus is the primary visual cortex, also known as visual area 1 (V1), Brodmann area 17, or the striate cortex. The extrastriate areas consist of visual areas 2, 3, 4, and 5.

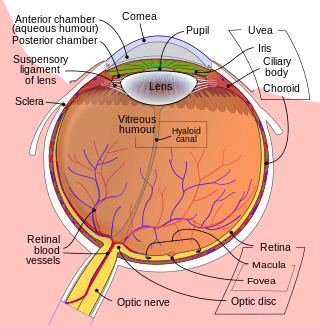

The retina is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then processes that image within the retina and sends nerve impulses along the optic nerve to the visual cortex to create visual perception. The retina serves a function which is in many ways analogous to that of the film or image sensor in a camera.

A saccade is a quick, simultaneous movement of both eyes between two or more phases of fixation in the same direction. In contrast, in smooth-pursuit movements, the eyes move smoothly instead of in jumps. The phenomenon can be associated with a shift in frequency of an emitted signal or a movement of a body part or device. Controlled cortically by the frontal eye fields (FEF), or subcortically by the superior colliculus, saccades serve as a mechanism for fixation, rapid eye movement, and the fast phase of optokinetic nystagmus. The word appears to have been coined in the 1880s by French ophthalmologist Émile Javal, who used a mirror on one side of a page to observe eye movement in silent reading, and found that it involves a succession of discontinuous individual movements.

An evoked potential or evoked response is an electrical potential in a specific pattern recorded from a specific part of the nervous system, especially the brain, of a human or other animals following presentation of a stimulus such as a light flash or a pure tone. Different types of potentials result from stimuli of different modalities and types. Evoked potential is distinct from spontaneous potentials as detected by electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), or other electrophysiologic recording method. Such potentials are useful for electrodiagnosis and monitoring that include detections of disease and drug-related sensory dysfunction and intraoperative monitoring of sensory pathway integrity.

The macula (/ˈmakjʊlə/) or macula lutea is an oval-shaped pigmented area in the center of the retina of the human eye and in other animals. The macula in humans has a diameter of around 5.5 mm (0.22 in) and is subdivided into the umbo, foveola, foveal avascular zone, fovea, parafovea, and perifovea areas.

Peripheral vision, or indirect vision, is vision as it occurs outside the point of fixation, i.e. away from the center of gaze or, when viewed at large angles, in the "corner of one's eye". The vast majority of the area in the visual field is included in the notion of peripheral vision. "Far peripheral" vision refers to the area at the edges of the visual field, "mid-peripheral" vision refers to medium eccentricities, and "near-peripheral", sometimes referred to as "para-central" vision, exists adjacent to the center of gaze.

The field of view (FOV) is the angular extent of the observable world that is seen at any given moment. In the case of optical instruments or sensors, it is a solid angle through which a detector is sensitive to electromagnetic radiation. It is further relevant in photography.

The visual system is the physiological basis of visual perception. The system detects, transduces and interprets information concerning light within the visible range to construct an image and build a mental model of the surrounding environment. The visual system is associated with the eye and functionally divided into the optical system and the neural system.

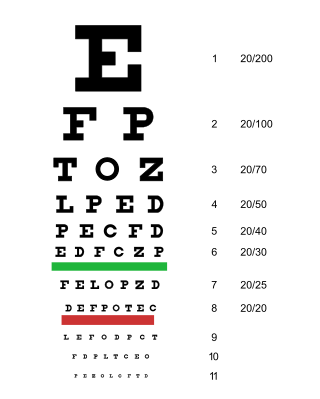

Visual acuity (VA) commonly refers to the clarity of vision, but technically rates an animal's ability to recognize small details with precision. Visual acuity depends on optical and neural factors. Optical factors of the eye influence the sharpness of an image on its retina. Neural factors include the health and functioning of the retina, of the neural pathways to the brain, and of the interpretative faculty of the brain.

The fovea centralis is a small, central pit composed of closely packed cones in the eye. It is located in the center of the macula lutea of the retina.

The receptive field, or sensory space, is a delimited medium where some physiological stimuli can evoke a sensory neuronal response in specific organisms.

Visual processing is a term that is used to refer to the brain's ability to use and interpret visual information from the world. The process of converting light energy into a meaningful image is a complex process that is facilitated by numerous brain structures and higher level cognitive processes. On an anatomical level, light energy first enters the eye through the cornea, where the light is bent. After passing through the cornea, light passes through the pupil and then lens of the eye, where it is bent to a greater degree and focused upon the retina. The retina is where a group of light-sensing cells, called photoreceptors are located. There are two types of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods are sensitive to dim light and cones are better able to transduce bright light. Photoreceptors connect to bipolar cells, which induce action potentials in retinal ganglion cells. These retinal ganglion cells form a bundle at the optic disc, which is a part of the optic nerve. The two optic nerves from each eye meet at the optic chiasm, where nerve fibers from each nasal retina cross which results in the right half of each eye's visual field being represented in the left hemisphere and the left half of each eye's visual fields being represented in the right hemisphere. The optic tract then diverges into two visual pathways, the geniculostriate pathway and the tectopulvinar pathway, which send visual information to the visual cortex of the occipital lobe for higher level processing.

Eye movement includes the voluntary or involuntary movement of the eyes. Eye movements are used by a number of organisms to fixate, inspect and track visual objects of interests. A special type of eye movement, rapid eye movement, occurs during REM sleep.

Retinotopy is the mapping of visual input from the retina to neurons, particularly those neurons within the visual stream. For clarity, 'retinotopy' can be replaced with 'retinal mapping', and 'retinotopic' with 'retinally mapped'.

In neuroanatomy, topographic map is the ordered projection of a sensory surface or an effector system to one or more structures of the central nervous system. Topographic maps can be found in all sensory systems and in many motor systems.

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision, color vision, scotopic vision, and mesopic vision, using light in the visible spectrum reflected by objects in the environment. This is different from visual acuity, which refers to how clearly a person sees. A person can have problems with visual perceptual processing even if they have 20/20 vision.

Feature detection is a process by which the nervous system sorts or filters complex natural stimuli in order to extract behaviorally relevant cues that have a high probability of being associated with important objects or organisms in their environment, as opposed to irrelevant background or noise.

In the human brain, the nucleus basalis, also known as the nucleus basalis of Meynert or nucleus basalis magnocellularis, is a group of neurons located mainly in the substantia innominata of the basal forebrain. Most neurons of the nucleus basalis are rich in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, and they have widespread projections to the neocortex and other brain structures.

Crowding is a perceptual phenomenon where the recognition of objects presented away from the fovea is impaired by the presence of other neighbouring objects. It has been suggested that crowding occurs due to mandatory integration of the crowded objects by a texture-processing neural mechanism, but there are several competing theories about the underlying mechanisms. It is considered a kind of grouping since it is "a form of integration over space as target features are spuriously combined with flanker features."

The eccentricity effect is a visual phenomenon that affects visual search. As retinal eccentricity increases, the observer is slower and less accurate to detect an item they are searching for.

References

- ↑ Barghout-Stein, Lauren. On differences between peripheral and foveal pattern masking. Diss. University of California, Berkeley, 1999.

- ↑ Daniel, P. M.; Whitteridge, D. (1961). "The representation of the visual field on the cerebral cortex in monkeys". Journal of Physiology. 159 (2): 203–221. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006803. PMC 1359500 . PMID 13883391.

- ↑ Cowey, A.; Rolls, E. T. (1974). "Human cortical magnification factor and its relation to visual acuity". Experimental Brain Research. 21 (5): 447–454. doi:10.1007/bf00237163. PMID 4442497. S2CID 14391226.

- 1 2 Strasburger, H.; Rentschler, I.; Jüttner, M. (2011). "Peripheral vision and pattern recognition: a review". Journal of Vision. 11 (5): 1–82. doi: 10.1167/11.5.13 . PMC 11073400 . PMID 22207654.