The laryngeal theory is a theory in historical linguistics positing that the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language included a number of laryngeal consonants that are not reconstructable by direct application of the comparative method to the Indo-European family. The "missing" sounds remain consonants of an indeterminate place of articulation towards the back of the mouth, though further information is difficult to derive. Proponents aim to use the theory to:

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Celtiberian or Northeastern Hispano-Celtic is an extinct Indo-European language of the Celtic branch spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula between the headwaters of the Douro, Tagus, Júcar and Turia rivers and the Ebro river. This language is directly attested in nearly 200 inscriptions dated from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD, mainly in Celtiberian script, a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, but also in the Latin alphabet. The longest extant Celtiberian inscriptions are those on three Botorrita plaques, bronze plaques from Botorrita near Zaragoza, dating to the early 1st century BC, labeled Botorrita I, III and IV. Shorter and more fragmentary is the Novallas bronze tablet.

Proto-Indo-European verbs reflect a complex system of morphology, more complicated than the substantive, with verbs categorized according to their aspect, using multiple grammatical moods and voices, and being conjugated according to person, number and tense. In addition to finite forms thus formed, non-finite forms such as participles are also extensively used.

The Proto-Greek language is the Indo-European language which was the last common ancestor of all varieties of Greek, including Mycenaean Greek, the subsequent ancient Greek dialects and, ultimately, Koine, Byzantine and Modern Greek. Proto-Greek speakers entered Greece sometime between 2200 and 1900 BC, with the diversification into a southern and a northern group beginning by approximately 1700 BC.

As the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) broke up, its sound system diverged as well, as evidenced in various sound laws associated with the daughter Indo-European languages. Especially notable is the palatalization that produced the satem languages, along with the associated ruki sound law. Other notable changes include:

Latin is a member of the broad family of Italic languages. Its alphabet, the Latin alphabet, emerged from the Old Italic alphabets, which in turn were derived from the Etruscan, Greek and Phoenician scripts. Historical Latin came from the prehistoric language of the Latium region, specifically around the River Tiber, where Roman civilization first developed. How and when Latin came to be spoken has long been debated.

Proto-Indo-European pronouns have been reconstructed by modern linguists, based on similarities found across all Indo-European languages. This article lists and discusses the hypothesised forms.

The numerals and derived numbers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) have been reconstructed by modern linguists based on similarities found across all Indo-European languages. The following article lists and discusses their hypothesized forms.

Sievers's law in Indo-European linguistics accounts for the pronunciation of a consonant cluster with a glide before a vowel as it was affected by the phonetics of the preceding syllable. Specifically, it refers to the alternation between *iy and *y, and possibly *uw and *w as conditioned by the weight of the preceding syllable. For instance, Proto-Indo-European (PIE) *kor-yo-s became Proto-Germanic *harjaz, Gothic harjis "army", but PIE *ḱerdh-yo-s became Proto-Germanic *hirdijaz, Gothic hairdeis "shepherd". It differs from ablaut in that the alternation has no morphological relevance but is phonologically context-sensitive: PIE *iy followed a heavy syllable, but *y would follow a light syllable.

Proto-Indo-European nominals include nouns, adjectives, and pronouns. Their grammatical forms and meanings have been reconstructed by modern linguists, based on similarities found across all Indo-European languages. This article discusses nouns and adjectives; Proto-Indo-European pronouns are treated elsewhere.

The phonology of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) has been reconstructed by linguists, based on the similarities and differences among current and extinct Indo-European languages. Because PIE was not written, linguists must rely on the evidence of its earliest attested descendants, such as Hittite, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin, to reconstruct its phonology.

Kluge's law is a controversial Proto-Germanic sound law formulated by Friedrich Kluge. It purports to explain the origin of the Proto-Germanic long consonants *kk, *tt, and *pp as originating in the assimilation of *n to a preceding voiced plosive consonant, under the condition that the *n was part of a suffix which was stressed in the ancestral Proto-Indo-European (PIE). The name "Kluge's law" was coined by Kauffmann (1887) and revived by Frederik Kortlandt (1991). As of 2006, this law has not been generally accepted by historical linguists.

Proto-Indo-European accent refers to the accentual (stress) system of the Proto-Indo-European language.

Osthoff's law is an Indo-European sound law which states that long vowels shorten when followed by a resonant, followed in turn by another consonant. It is named after German Indo-Europeanist Hermann Osthoff, who first formulated it.

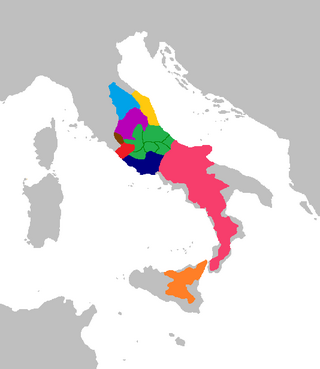

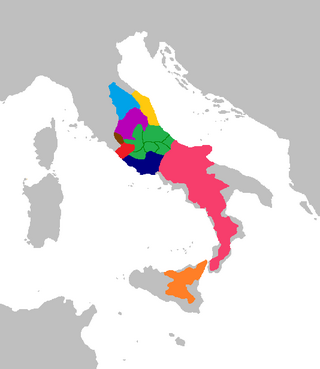

Languages of the Indo-European family are classified as either centum languages or satem languages according to how the dorsal consonants of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) developed. An example of the different developments is provided by the words for "hundred" found in the early attested Indo-European languages. In centum languages, they typically began with a sound, but in satem languages, they often began with.

The boukólos rule is a phonological rule of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). It states that a labiovelar stop dissimilates to an ordinary velar stop next to the vowel *u or its corresponding glide *w.

The Proto-Italic language is the ancestor of the Italic languages, most notably Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. It is not directly attested in writing, but has been reconstructed to some degree through the comparative method. Proto-Italic descended from the earlier Proto-Indo-European language.

This glossary gives a general overview of the various sound laws that have been formulated by linguists for the various Indo-European languages. A concise description is given for each rule; more details are given in their respective articles.

Cowgill's law says that a former vowel becomes between a resonant and a labial consonant, in either order. It is named after Indo-Europeanist Warren Cowgill.