Related Research Articles

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of the defining features of marsupials is their unique reproductive strategy, where the young are born in a relatively undeveloped state and then nurtured within a pouch on their mother's abdomen.

Ungulates are members of the diverse clade Euungulata, which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to be a polyphyletic and thereby invalid clade based on molecular data. As a result, true ungulates had since been reclassified to the newer clade Euungulata in 2001 within the clade Laurasiatheria while Paenungulata has been reclassified to a distant clade Afrotheria. Living ungulates are divided into two orders: Perissodactyla including equines, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and Artiodactyla including cattle, antelope, pigs, giraffes, camels, sheep, deer, and hippopotamuses, among others. Cetaceans such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises are also classified as artiodactyls, although they do not have hooves. Most terrestrial ungulates use the hoofed tips of their toes to support their body weight while standing or moving. Two other orders of ungulates, Notoungulata and Litopterna, both native to South America, became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago.

Multituberculata is an extinct order of rodent-like mammals with a fossil record spanning over 130 million years. They first appeared in the Middle Jurassic, and reached a peak diversity during the Late Cretaceous and Paleocene. They eventually declined from the mid-Paleocene onwards, disappearing from the known fossil record in the late Eocene. They are the most diverse order of Mesozoic mammals with more than 200 species known, ranging from mouse-sized to beaver-sized. These species occupied a diversity of ecological niches, ranging from burrow-dwelling to squirrel-like arborealism to jerboa-like hoppers. Multituberculates are usually placed as crown mammals outside either of the two main groups of living mammals—Theria, including placentals and marsupials, and Monotremata—but usually as closer to Theria than to monotremes. They are considered to be closely related to Euharamiyida and Gondwanatheria as part of Allotheria.

Synapsida is one of the two major clades of vertebrate animals in the group Amniota, the other being the Sauropsida. The synapsids were the dominant land animals in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic, but the only group that survived into the Cenozoic are mammals. Unlike other amniotes, synapsids have a single temporal fenestra, an opening low in the skull roof behind each eye orbit, leaving a bony arch beneath each; this accounts for their name. The distinctive temporal fenestra developed about 318 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period, when synapsids and sauropsids diverged, but was subsequently merged with the orbit in early mammals.

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structures at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term jaws is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serving to open and close it and is part of the body plan of humans and most animals.

A saber-tooth is any member of various extinct groups of predatory therapsids, predominantly carnivoran mammals, that are characterized by long, curved saber-shaped canine teeth which protruded from the mouth when closed. Saber-toothed mammals have been found almost worldwide from the Eocene epoch to the end of the Pleistocene epoch.

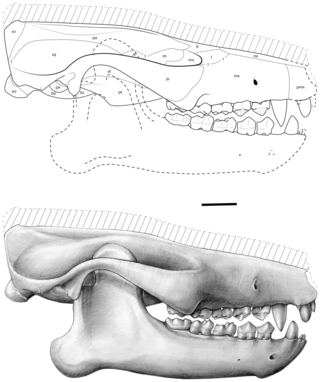

Thylacosmilus is an extinct genus of saber-toothed metatherian mammals that inhabited South America from the Late Miocene to Pliocene epochs. Though Thylacosmilus looks similar to the "saber-toothed cats", it was not a felid, like the well-known North American Smilodon, but a sparassodont, a group closely related to marsupials, and only superficially resembled other saber-toothed mammals due to convergent evolution. A 2005 study found that the bite forces of Thylacosmilus and Smilodon were low, which indicates the killing-techniques of saber-toothed animals differed from those of extant species. Remains of Thylacosmilus have been found primarily in Catamarca, Entre Ríos, and La Pampa Provinces in northern Argentina.

Carnassials are paired upper and lower teeth modified in such a way as to allow enlarged and often self-sharpening edges to pass by each other in a shearing manner. This adaptation is found in carnivorans, where the carnassials are the modified fourth upper premolar and the first lower molar. These teeth are also referred to as sectorial teeth.

Biarmosuchia is an extinct clade of non-mammalian synapsids from the Permian. Biarmosuchians are the most basal group of the therapsids. They were moderately-sized, lightly built carnivores, intermediate in form between basal sphenacodont "pelycosaurs" and more advanced therapsids. Biarmosuchians were rare components of Permian ecosystems, and the majority of species belong to the clade Burnetiamorpha, which are characterized by elaborate cranial ornamentation.

The evolution of mammals has passed through many stages since the first appearance of their synapsid ancestors in the Pennsylvanian sub-period of the late Carboniferous period. By the mid-Triassic, there were many synapsid species that looked like mammals. The lineage leading to today's mammals split up in the Jurassic; synapsids from this period include Dryolestes, more closely related to extant placentals and marsupials than to monotremes, as well as Ambondro, more closely related to monotremes. Later on, the eutherian and metatherian lineages separated; the metatherians are the animals more closely related to the marsupials, while the eutherians are those more closely related to the placentals. Since Juramaia, the earliest known eutherian, lived 160 million years ago in the Jurassic, this divergence must have occurred in the same period.

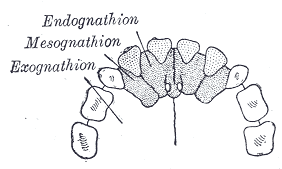

The premaxilla is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals has been usually termed as the incisive bone. Other terms used for this structure include premaxillary bone or os premaxillare, intermaxillary bone or os intermaxillare, and Goethe's bone.

Cranial kinesis is the term for significant movement of skull bones relative to each other in addition to movement at the joint between the upper and lower jaws. It is usually taken to mean relative movement between the upper jaw and the braincase.

Apatemyidae is an extinct family of placental mammals that took part in the first placental evolutionary radiation together with other early mammals, such as the leptictids. Their relationships to other mammal groups are controversial; a 2010 study found them to be basal members of Euarchontoglires.

Bite force quotient (BFQ) is a numerical value commonly used to represent the bite force of an animal adjusted for its body mass, while also taking factors like the allometry effects.

Thylacosmilidae is an extinct family of metatherian predators, related to the modern marsupials, which lived in South America between the Miocene and Pliocene epochs. Like other South American mammalian predators that lived prior to the Great American Biotic Interchange, these animals belonged to the order Sparassodonta, which occupied the ecological niche of many eutherian mammals of the order Carnivora from other continents. The family's most notable feature are the elongated, laterally flattened fangs, which is a remarkable evolutionary convergence with other saber-toothed mammals like Barbourofelis and Smilodon.

Ocepeia is an extinct genus of afrotherian mammal that lived in present-day Morocco during the middle Paleocene epoch, approximately 60 million years ago. First named and described in 2001, the type species is O. daouiensis from the Selandian stage of Morocco's Ouled Abdoun Basin. A second, larger species, O. grandis, is known from the Thanetian, a slightly younger stage in the same area. In life, the two species are estimated to have weighed about 3.5 kg (7.7 lb) and 10 kg (22 lb), respectively, and are believed to have been specialized leaf-eaters. The fossil skulls of Ocepeia are the oldest known afrotherian skulls, and the best-known of any Paleocene mammal in Africa.

Simosthenurus occidentalis is a species of sthenurine marsupial that existed in Australia during the Pliocene, becoming extinct in the Pleistocene epoch around 42,000 years ago. It was a large herbivorous biped that resembles large kangaroos, but with a heavier body than modern kangaroos. The structure of the skull and teeth - resembling koalas and panda bears - indicates that it consumed tough vegetation.

Hyaenodonta is an extinct order of hypercarnivorous placental mammals of clade Pan-Carnivora from mirorder Ferae. Hyaenodonts were important mammalian predators that arose during the early Paleocene in Europe and persisted well into the late Miocene.

Anatoliadelphys maasae is an extinct genus of predatory metatherian mammal from the Eocene of Anatolia. It was an arboreal, cat-sized animal, with powerful crushing jaws similar to those of the modern Tasmanian devil. Although most mammalian predators of the northern hemisphere in this time period were placentals, Europe was an archipelago, and the island landmass now forming Turkey might have been devoid of competing mammalian predators, though this may not matter since other carnivorous metatherians are also known from the Cenozoic in the Northern Hemisphere. Nonetheless, it stands as a reminder that mammalian faunas in the Paleogene of the Northern Hemisphere were more complex than previously thought, and metatherians did not immediately lose their hold as major predators after their success in the Cretaceous.

Periptychus is an extinct genus of mammal belonging to the family Periptychidae. It lived from the Early to Late Paleocene and its fossil remains have been found in North America.

References

- ↑ Marta Linde-Medina (September 2016). "Testing the cranial evolutionary allometric 'rule' in Galliformes". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 9 (29): 1873–1878. doi:10.1111/jeb.12918. PMC 5021629 . PMID 27306761.

- ↑ Andrea Cardini (2016). "96th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Mammalogists" (PDF). p. 53.

- ↑ Cardini, A., Polly, D., Dawson, R., Milne, N., 2015. Why the Long Face? Kangaroos and Wallabies Follow the Same ‘Rule’ of Cranial Evolutionary Allometry (CREA) as Placentals. Evol Biol 42, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-015-9308-9

- ↑ Tamagnini, D., Meloro, C., Cardini, A., 2017. Anyone with a Long-Face? Craniofacial Evolutionary Allometry (CREA) in a Family of Short-Faced Mammals, the Felidae. Evol Biol 44, 476–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-017-9421-z

- ↑ Cardini, A., Polly, P.D., 2013. Larger mammals have longer faces because of size-related constraints on skull form. Nat Commun 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3458

- ↑ Mitchell, D. Rex; Sherratt, Emma; Weisbecker, Vera (29 November 2023). "Facing the facts: adaptive trade‐offs along body size ranges determine mammalian craniofacial scaling". Biological Reviews. 99 (2): 496–524. doi:10.1111/brv.13032. hdl: 2440/141309 . ISSN 1464-7931 – via Wiley.