The broken windows theory is a criminological theory that visible signs of crime, anti-social behavior, and civil disorder create an urban environment that encourages further crime and disorder, including serious crimes. The theory suggests that policing methods that target minor crimes such as vandalism, public drinking, and fare evasion help to create an atmosphere of order and lawfulness, thereby preventing more serious crimes.

In criminology, blue-collar crime is any crime committed by an individual from a lower social class as opposed to white-collar crime which is associated with crime committed by someone of a higher-level social class. While blue-collar crime has no official legal classification, it holds to a general net group of crimes. These crimes are primarily small scale, for immediate beneficial gain to the individual or group involved in them. This can also include personal related crimes that can be driven by immediate reaction, such as during fights or confrontations. These crimes include but are not limited to: Narcotic production or distribution, sexual assault, theft, burglary, assault or murder.

Geographic profiling is a criminal investigative methodology that analyzes the locations of a connected series of crimes to determine the most probable area of offender residence. By incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods, it assists in understanding spatial behaviour of an offender and focusing the investigation to a smaller area of the community. Typically used in cases of serial murder or rape, the technique helps police detectives prioritize information in large-scale major crime investigations that often involve hundreds or thousands of suspects and tips.

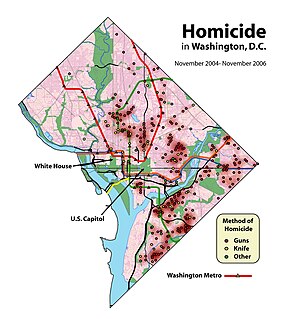

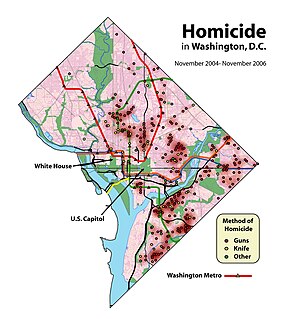

Crime mapping is used by analysts in law enforcement agencies to map, visualize, and analyze crime incident patterns. It is a key component of crime analysis and the CompStat policing strategy. Mapping crime, using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), allows crime analysts to identify crime hot spots, along with other trends and patterns.

Crime science is the study of crime in order to find ways to prevent it. Three features distinguish crime science from criminology: it is single-minded about cutting crime, rather than studying it for its own sake; accordingly it focuses on crime rather than criminals; and it is multidisciplinary, notably recruiting scientific methodology rather than relying on social theory.

Environmental criminology focuses on criminal patterns within particular built environments and analyzes the impacts of these external variables on people's cognitive behavior. It forms a part of criminology's Positivist School in that it applies the scientific method to examine the society that causes crime.

Right realism, in criminology, also known as New Right Realism, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Positivism, or Neo-Conservatism, is the ideological polar opposite of left realism. It considers the phenomenon of crime from the perspective of political Conservatism and asserts that it takes a more realistic view of the causes of crime and deviance, and identifies the best mechanisms for its control. Unlike the other Schools of criminology, there is less emphasis on developing theories of causality in relation to crime and deviance. The school employs a rationalist, direct and scientific approach to policy-making for the prevention and control of crime. Some politicians who ascribe to the perspective may address aspects of crime policy in ideological terms by referring to freedom, justice, and responsibility. For example, they may be asserting that individual freedom should only be limited by a duty not to use force against others. This, however, does not reflect the genuine quality in the theoretical and academic work and the real contribution made to the nature of criminal behaviour by criminologists of the school.

In criminology, rational choice theory adopts a utilitarian belief that man is a reasoning actor who weighs means and ends, costs and benefits, and makes a rational choice. This method was designed by Cornish and Clarke to assist in thinking about situational crime prevention. It is assumed that crime is purposive behavior designed to meet the offender’s commonplace needs for such things as money, status, sex and excitement, and that meeting these needs involves the making of decisions and choices, constrained as these are by limits, ability, and the availability of relevant information...

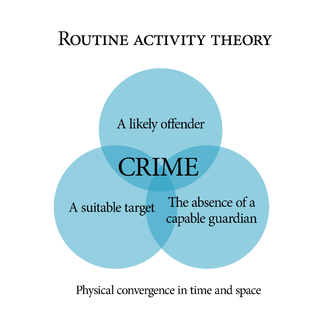

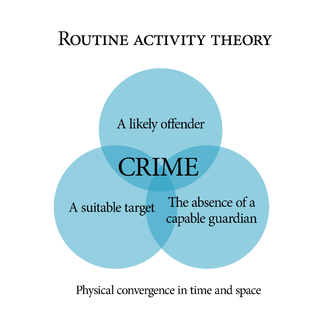

Routine activity theory is a sub-field of crime opportunity theory that focuses on situations of crimes. It was first proposed by Marcus Felson and Lawrence E. Cohen in their explanation of crime rate change in the United States 1947 - 1974. The theory has been extensively applied and has become one of the most cited theories in criminology. Unlike criminological theories of criminality, routine activity theory studies crime as an event, closely relates crime to its environment and emphasize its ecological process, thereby diverting academic attention away from mere offenders.

Lawrence W. Sherman is an American experimental criminologist and police educator who is the founder of evidence-based policing.

Biosocial criminology is an interdisciplinary field that aims to explain crime and antisocial behavior by exploring both biological factors and environmental factors. While contemporary criminology has been dominated by sociological theories, biosocial criminology also recognizes the potential contributions of fields such as genetics, neuropsychology, and evolutionary psychology.

Criminology is the scientific study of the nature, extent, management, causes, control, consequences, and prevention of criminal behavior, both on individual and social levels. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioral and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, biologists, social anthropologists, as well as scholars of law.

David L. Weisburd, is an Israeli/American criminologist who is well known for his research on crime and place, policing and white collar crime. Weisburd was the 2010 recipient of the prestigious Stockholm Prize in Criminology, and was recently awarded the Israel Prize in Social Work and Criminological Research, considered the state's highest honor. Weisburd holds joint tenured appointments as Distinguished Professor of Criminology, Law and Society at George Mason University. and Walter E. Meyer Professor of Law and Criminal Justice in the Institute of Criminology of the Hebrew University Faculty of Law, At George Mason University Weisburd was founder of the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy and is now its executive director. Weisburd also serves as Chief Science Advisor at the National Police Foundation in Washington, D.C., and chair of its Research Advisory Committee. Weisburd was the founding editor of the Journal of Experimental Criminology, and is now the general editor of the Journal of Quantitative Criminology.

The idea of regulatory crime control is to reduce and control crime. Many factors can make a place or area a victim of criminal activity. John and Emily Eck, two primary scholars that work within the area of regulatory crime control, explain how places can either create crime opportunities or crime barriers (2012). Eck also defines the two types of regulatory crime control strategies as ends-based and means-based. He states that means-based strategies focus on the use of different procedures and technologies, while ends-based strategies concentrate on the overall outcome (2012). Another primary scholar, Graham Farrell, discusses how repeat victimization is becoming an important area for policing and crime control.

Crime Opportunity theory suggests that offenders make rational choices and thus choose targets that offer a high reward with little effort and risk. The occurrence of a crime depends on two things: the presence of at least one motivated offender who is ready or willing to engage in a crime, and the conditions of the environment in which that offender is situated, to wit, opportunities for crime. All crimes require opportunity but not every opportunity is followed by crime. Similarly, a motivated offender is necessary for the commission of a crime but not sufficient. A large part of this theory focuses on how variations in lifestyle or routine activities affect the opportunities for crime.

A Crime concentration is a spatial area to which high levels of crime incidents are attributed. A crime concentration can be the result of homogeneous or heterogeneous crime incidents. Hotspots are the result of various crimes occurring in relative proximity to each other within predefined human geopolitical or social boundaries. Crime concentrations are smaller units or set of crime targets within a hotspot. A single or a conjunction of crime concentrations within a study area can make up a crime hotspot.

Crime Pattern Theory is a way of explaining why crimes are committed in certain areas. Crime is not random, it is either planned or opportunistic. According to the theory crime happens when the activity space of a victim or target intersects with the activity space of an offender. A person's activity space consists of locations in everyday life, for example home, work, school, shopping areas, entertainment areas etc. These personal locations are also called nodes. The course or route a person takes to and from these nodes are called personal paths. Personal paths connect with various nodes creating a perimeter. This perimeter is a person's awareness space. Crime Pattern Theory claims that a crime involving an offender and a victim or target can only occur when the activity spaces of both cross paths. Simply put crime will occur if an area provides opportunity for crime and it exists within an offender's awareness space. Consequently, an area that provides shopping, recreation and restaurants such as a shopping mall has a higher rate of crime. This is largely due to the high number of potential victims and offenders visiting the area and the various targets in the area. It is highly probable that an area like this will have a lot of car theft because of all the traffic in and out of the area. It is also probable that people may fall victim of purse snatching or pick pocketing because victims typically carry cash with them. Therefore, crime pattern theory provides analysts an organized way to explore patterns of behaviour. Criminals come across new opportunities for crime every day. These opportunities arise as they go to and from personal nodes using personal paths. For example, a victim could enter an offender's awareness space by way of a liquor store parking lot or a new shopping center being built. If the shopping center is being built in an area where crime occurs a couple of miles away, chances are it will exist in some if not all offender's awareness space. This theory aids law enforcement in figuring out why crime exists in certain areas. It also helps predict where certain crimes may occur.