Related Research Articles

The history of Slovenia chronicles the period of the Slovenian territory from the 5th century BC to the present. In the Early Bronze Age, Proto-Illyrian tribes settled an area stretching from present-day Albania to the city of Trieste. The Slovenian territory was part of the Roman Empire, and it was devastated by the Migration Period's incursions during late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. The main route from the Pannonian plain to Italy ran through present-day Slovenia. Alpine Slavs, ancestors of modern-day Slovenians, settled the area in the late 6th Century AD. The Holy Roman Empire controlled the land for nearly 1,000 years. Between the mid-14th century through 1918 most of Slovenia was under Habsburg rule. In 1918, most Slovene territory became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and in 1929 the Drava Banovina was created within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia with its capital in Ljubljana, corresponding to Slovenian-majority territories within the state. The Socialist Republic of Slovenia was created in 1945 as part of federal Yugoslavia. Slovenia gained its independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991, and today it is a member of the European Union and NATO.

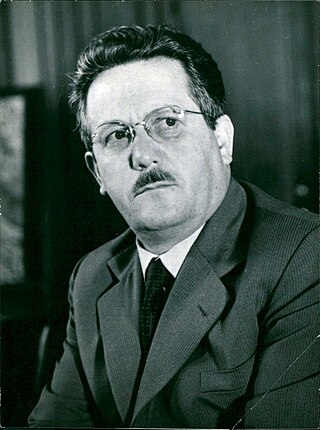

Edvard Kardelj, also known by the pseudonyms Bevc, Sperans, and Krištof, was a Yugoslav politician and economist. He was one of the leading members of the Communist Party of Slovenia before World War II. During the war, Kardelj was one of the leaders of the Liberation Front of the Slovenian People and a Slovene Partisan. After the war, he was a federal political leader in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. He led the Yugoslav delegation in peace talks with Italy over the border dispute in the Julian March.

TIGR, fully the Revolutionary Organization of the Julian March T.I.G.R., was a militant anti-fascist and insurgent organization established as a response to the Fascist Italianization of the Slovene and Croat people on part of the former Austro-Hungarian territories that became part of Italy after the First World War, and were known at the time as the Julian March. It is considered one of the first anti-fascist resistance movements in Europe. It was active between 1927 and 1941.

The University of Ljubljana, abbreviated UL, is the oldest and largest university in Slovenia. It has approximately 38,000 enrolled students. The university has 23 faculties and three art academies with approximately 4,000 teaching and research staff, assisted by approximately 2,000 technical and administrative staff. The University of Ljubljana offers programs in the humanities, sciences, and technology, as well as in medicine, dentistry, and veterinary science.

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians, are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovene as their native language. According to ethnic classification based on language, they are closely related to other South Slavic ethnic groups, as well as more distantly to West Slavs.

The Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts is the national academy of Slovenia, which encompasses science and the arts and brings together the top Slovene researchers and artists as members of the academy.

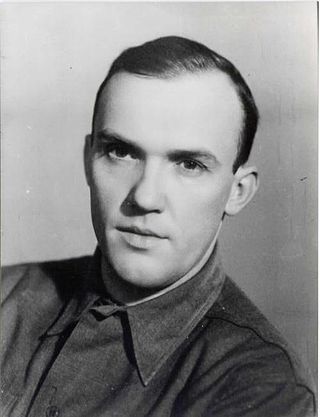

Leon Rupnik, also known as Lav Rupnik or Lev Rupnik was a Slovene general in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia who collaborated with the Fascist Italian and Nazi German occupation forces during World War II. Rupnik served as the President of the Provincial Government of the Nazi-occupied Province of Ljubljana from November 1943 to early May 1945. Between September 1944 and early May 1945, he also served as chief inspector of the Slovene Home Guard, a collaborationist militia, although he did not have any military command until the last month of the war.

The Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation, or simply Liberation Front, originally called the Anti-Imperialist Front, was a Slovene anti-fascist political party. The Anti-Imperialist Front had ideological ties to the Soviet Union in its fight against the imperialistic tendencies of the United States and the United Kingdom, and it was led by the Communist Party of Slovenia. In May 1941, weeks into the German occupation of Yugoslavia, in the first wartime issue of the illegal newspaper Slovenski poročevalec, members of the organization criticized the German regime and described Germans as imperialists. They started raising money for a liberation fund via the second issue of the newspaper published on 8 June 1941. When Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the Anti-Imperialist Front was formally renamed and became the main anti-fascist Slovene civil resistance and political organization under the guidance and control of the Slovene communists. It was active in the Slovene Lands during World War II. Its military arm was the Slovene Partisans. The organisation was established in the Province of Ljubljana on 26 April 1941 in the house of the literary critic Josip Vidmar. Its leaders were Boris Kidrič and Edvard Kardelj.

The Slovene Home Guard was a Slovene anti-Partisan collaborationist militia that operated during the 1943–1945 German occupation of the formerly Italian-annexed Slovene Province of Ljubljana. The Guard consisted of former Village Sentries, part of Italian-sponsored Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia, re-organized under Nazi command after the Italian Armistice of September 1943.

Gregorij Rožman was a Slovenian Roman Catholic prelate. Between 1930 and 1959, he served as bishop of the Diocese of Ljubljana. He may be best-remembered for his controversial role during World War II. Rožman was an ardent anti-communist and opposed the Liberation Front of the Slovene People and the Partisan forces because they were led by the Communist party. He established relations with both the fascist and Nazi occupying powers, issued proclamations of support for the occupying authorities, and supported armed collaborationist forces organized by the fascist and Nazi occupiers. The Yugoslav Communist government convicted him in absentia in August 1946 of treason for collaborating with the Nazis against the Yugoslav resistance. In 2009, his conviction was annulled on procedural grounds.

The Province of Ljubljana was the central-southern area of Slovenia. In 1941, it was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy, and after 1943 occupied by Nazi Germany. Created on May 3, 1941, it was abolished on May 9, 1945, when the Slovene Partisans and partisans from other parts of Yugoslavia liberated it from the Nazi Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral. Its administrative centre was Ljubljana.

Matej Bor was the pen name of Vladimir Pavšič, who was a Slovene poet, translator, playwright, journalist and Partisan.

Tivoli City Park or simply Tivoli Park is the largest park in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. It is located on the western outskirts of the Center District, stretching to the Šiška District to the north, the Vič District to the south, and the Rožnik District to the west. Several notable buildings and art works stand in the park. Since 1984, the park has been protected as part of Tivoli–Rožnik Hill–Šiška Hill Nature Park. It is home to a variety of bird species.

The Slovene Society is the second-oldest publishing house in Slovenia, founded on 4 February 1864 as an institution for the scholarly and cultural progress of Slovenes.

Dušan Pirjevec, known by his nom de guerre Ahac, was a Slovenian Partisan, literary historian and philosopher. He was one of the most influential public intellectuals in post–World War II Slovenia.

Bogo Grafenauer was a Slovenian historian, who mostly wrote about medieval history in the Slovene Lands. Together with Milko Kos, Fran Zwitter, and Vasilij Melik, he was one of the founders of the so-called Ljubljana school of historiography.

Janko Pleterski was a Slovenian historian, politician and diplomat. He was the father of the historian and archeologist Andrej Pleterski.

The Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia were paramilitary auxiliary formations of the Royal Italian Army composed of Yugoslav anti-Partisan groups in the Italian-annexed and occupied portions of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the Second World War.

The Slovene Partisans, formally the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Slovenia, were part of Europe's most effective anti-Nazi resistance movement led by Yugoslav revolutionary communists during World War II, the Yugoslav Partisans. Since a quarter of Slovene ethnic territory and approximately 327,000 out of total population of 1.3 million Slovenes were subjected to forced Italianization after the end of the First World War, and genocide of the entire Slovene nation was being planned by the Italian fascist authorities, the objective of the movement was the establishment of the state of Slovenes that would include the majority of Slovenes within a socialist Yugoslav federation in the postwar period.

World War II in the Slovene Lands started in April 1941 and lasted until May 1945. The Slovene Lands were in a unique situation during World War II in Europe. In addition to being trisected, a fate which also befell Greece, Drava Banovina was the only region that experienced a further step—absorption and annexation into neighboring Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Hungary. The Slovene-settled territory was divided largely between Nazi Germany and the Kingdom of Italy, with smaller territories occupied and annexed by Hungary and the Independent State of Croatia.

References

- 1 2 "Akademija znanosti in umetnosti kršila kulturni molk" [The Academy of Sciences and Arts Has Breached the Cultural Silence]. 23 January 2011. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- 1 2 Klemenčič, Matjaž; Žagar, Mitja (2004). "Histories of the Individual Yugoslav Nations". The former Yugoslavia's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook . ABC-Clio, Inc. pp. 180.

The former Yugoslavia's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook.

- ↑ Dolgan, Marjan, Jerneja Fridl, & Manca Volk. 2014. Literarni atlas Ljubljane. Zgode in nezgode 94 slovenskih književnikov v Ljubljani. Ljubljana: ZRC, pp. 62, 70, 135, 175.