The Beer–Bouguer–Lambert (BBL) extinction law is an empirical relationship describing the attenuation in intensity of a radiation beam passing through a macroscopically homogenous medium with which it interacts. Formally, it states that the intensity of radiation decays exponentially in the absorbance of the medium, and that said absorbance is proportional to the length of beam passing through the medium, the concentration of interacting matter along that path, and a constant representing said matter's propensity to interact.

An aerosol is a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be generated from natural or human causes. The term aerosol commonly refers to the mixture of particulates in air, and not to the particulate matter alone. Examples of natural aerosols are fog, mist or dust. Examples of human caused aerosols include particulate air pollutants, mist from the discharge at hydroelectric dams, irrigation mist, perfume from atomizers, smoke, dust, sprayed pesticides, and medical treatments for respiratory illnesses.

The Knudsen number (Kn) is a dimensionless number defined as the ratio of the molecular mean free path length to a representative physical length scale. This length scale could be, for example, the radius of a body in a fluid. The number is named after Danish physicist Martin Knudsen (1871–1949).

In physics, mathematics and statistics, scale invariance is a feature of objects or laws that do not change if scales of length, energy, or other variables, are multiplied by a common factor, and thus represent a universality.

A granular material is a conglomeration of discrete solid, macroscopic particles characterized by a loss of energy whenever the particles interact. The constituents that compose granular material are large enough such that they are not subject to thermal motion fluctuations. Thus, the lower size limit for grains in granular material is about 1 μm. On the upper size limit, the physics of granular materials may be applied to ice floes where the individual grains are icebergs and to asteroid belts of the Solar System with individual grains being asteroids.

Electrical mobility is the ability of charged particles to move through a medium in response to an electric field that is pulling them. The separation of ions according to their mobility in gas phase is called ion mobility spectrometry, in liquid phase it is called electrophoresis.

A Coulomb collision is a binary elastic collision between two charged particles interacting through their own electric field. As with any inverse-square law, the resulting trajectories of the colliding particles is a hyperbolic Keplerian orbit. This type of collision is common in plasmas where the typical kinetic energy of the particles is too large to produce a significant deviation from the initial trajectories of the colliding particles, and the cumulative effect of many collisions is considered instead. The importance of Coulomb collisions was first pointed out by Lev Landau in 1936, who also derived the corresponding kinetic equation which is known as the Landau kinetic equation.

In quantum field theory, and specifically quantum electrodynamics, vacuum polarization describes a process in which a background electromagnetic field produces virtual electron–positron pairs that change the distribution of charges and currents that generated the original electromagnetic field. It is also sometimes referred to as the self-energy of the gauge boson (photon).

The diffusion of plasma across a magnetic field was conjectured to follow the Bohm diffusion scaling as indicated from the early plasma experiments of very lossy machines. This predicted that the rate of diffusion was linear with temperature and inversely linear with the strength of the confining magnetic field.

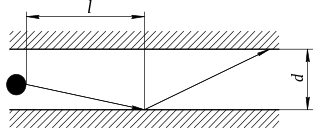

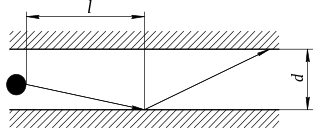

Knudsen diffusion, named after Martin Knudsen, is a means of diffusion that occurs when the scale length of a system is comparable to or smaller than the mean free path of the particles involved. An example of this is in a long pore with a narrow diameter (2–50 nm) because molecules frequently collide with the pore wall. As another example, consider the diffusion of gas molecules through very small capillary pores. If the pore diameter is smaller than the mean free path of the diffusing gas molecules, and the density of the gas is low, the gas molecules collide with the pore walls more frequently than with each other, leading to Knudsen diffusion.

The linear attenuation coefficient, attenuation coefficient, or narrow-beam attenuation coefficient characterizes how easily a volume of material can be penetrated by a beam of light, sound, particles, or other energy or matter. A coefficient value that is large represents a beam becoming 'attenuated' as it passes through a given medium, while a small value represents that the medium had little effect on loss. The (derived) SI unit of attenuation coefficient is the reciprocal metre (m−1). Extinction coefficient is another term for this quantity, often used in meteorology and climatology. Most commonly, the quantity measures the exponential decay of intensity, that is, the value of downward e-folding distance of the original intensity as the energy of the intensity passes through a unit thickness of material, so that an attenuation coefficient of 1 m−1 means that after passing through 1 metre, the radiation will be reduced by a factor of e, and for material with a coefficient of 2 m−1, it will be reduced twice by e, or e2. Other measures may use a different factor than e, such as the decadic attenuation coefficient below. The broad-beam attenuation coefficient counts forward-scattered radiation as transmitted rather than attenuated, and is more applicable to radiation shielding. The mass attenuation coefficient is the attenuation coefficient normalized by the density of the material.

Free molecular flow describes the fluid dynamics of gas where the mean free path of the molecules is larger than the size of the chamber or of the object under test. For tubes/objects of the size of several cm, this means pressures well below 10−3 mbar. This is also called the regime of high vacuum, or even ultra-high vacuum. This is opposed to viscous flow encountered at higher pressures. The presence of free molecular flow can be calculated, at least in estimation, with the Knudsen number (Kn). If Kn > 10, the system is in free molecular flow, also known as Knudsen flow. Knudsen flow has been defined as the transitional range between viscous flow and molecular flow, which is significant in the medium vacuum range where λ ≈ d.

In non ideal fluid dynamics, the Hagen–Poiseuille equation, also known as the Hagen–Poiseuille law, Poiseuille law or Poiseuille equation, is a physical law that gives the pressure drop in an incompressible and Newtonian fluid in laminar flow flowing through a long cylindrical pipe of constant cross section. It can be successfully applied to air flow in lung alveoli, or the flow through a drinking straw or through a hypodermic needle. It was experimentally derived independently by Jean Léonard Marie Poiseuille in 1838 and Gotthilf Heinrich Ludwig Hagen, and published by Hagen in 1839 and then by Poiseuille in 1840–41 and 1846. The theoretical justification of the Poiseuille law was given by George Stokes in 1845.

In fluid dynamics, the Oseen equations describe the flow of a viscous and incompressible fluid at small Reynolds numbers, as formulated by Carl Wilhelm Oseen in 1910. Oseen flow is an improved description of these flows, as compared to Stokes flow, with the (partial) inclusion of convective acceleration.

The primary application of wind turbines is to generate energy using the wind. Hence, the aerodynamics is a very important aspect of wind turbines. Like most machines, wind turbines come in many different types, all of them based on different energy extraction concepts.

Chapman–Enskog theory provides a framework in which equations of hydrodynamics for a gas can be derived from the Boltzmann equation. The technique justifies the otherwise phenomenological constitutive relations appearing in hydrodynamical descriptions such as the Navier–Stokes equations. In doing so, expressions for various transport coefficients such as thermal conductivity and viscosity are obtained in terms of molecular parameters. Thus, Chapman–Enskog theory constitutes an important step in the passage from a microscopic, particle-based description to a continuum hydrodynamical one.

Pitzer equations are important for the understanding of the behaviour of ions dissolved in natural waters such as rivers, lakes and sea-water. They were first described by physical chemist Kenneth Pitzer. The parameters of the Pitzer equations are linear combinations of parameters, of a virial expansion of the excess Gibbs free energy, which characterise interactions amongst ions and solvent. The derivation is thermodynamically rigorous at a given level of expansion. The parameters may be derived from various experimental data such as the osmotic coefficient, mixed ion activity coefficients, and salt solubility. They can be used to calculate mixed ion activity coefficients and water activities in solutions of high ionic strength for which the Debye–Hückel theory is no longer adequate. They are more rigorous than the equations of specific ion interaction theory, but Pitzer parameters are more difficult to determine experimentally than SIT parameters.

In computational fluid dynamics, the Stochastic Eulerian Lagrangian Method (SELM) is an approach to capture essential features of fluid-structure interactions subject to thermal fluctuations while introducing approximations which facilitate analysis and the development of tractable numerical methods. SELM is a hybrid approach utilizing an Eulerian description for the continuum hydrodynamic fields and a Lagrangian description for elastic structures. Thermal fluctuations are introduced through stochastic driving fields. Approaches also are introduced for the stochastic fields of the SPDEs to obtain numerical methods taking into account the numerical discretization artifacts to maintain statistical principles, such as fluctuation-dissipation balance and other properties in statistical mechanics.

In the science of fluid flow, Stokes' paradox is the phenomenon that there can be no creeping flow of a fluid around a disk in two dimensions; or, equivalently, the fact there is no non-trivial steady-state solution for the Stokes equations around an infinitely long cylinder. This is opposed to the 3-dimensional case, where Stokes' method provides a solution to the problem of flow around a sphere.

Propeller theory is the science governing the design of efficient propellers. A propeller is the most common propulsor on ships, and on small aircraft.