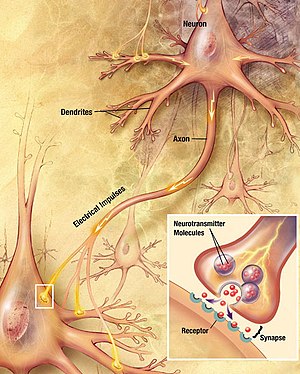

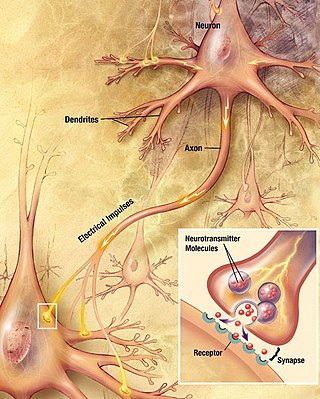

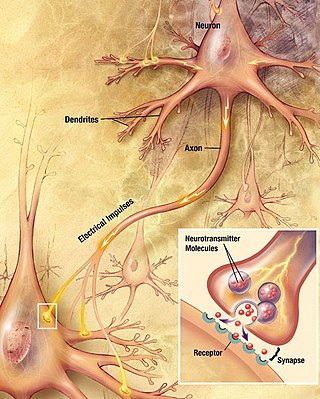

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network in the nervous system. Neurons communicate with other cells via synapses, which are specialized connections that commonly use minute amounts of chemical neurotransmitters to pass the electric signal from the presynaptic neuron to the target cell through the synaptic gap.

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

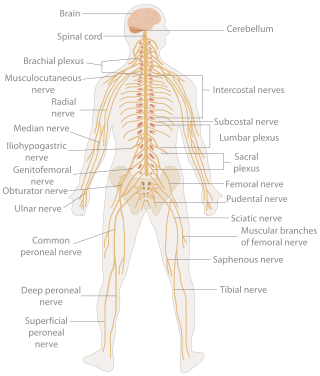

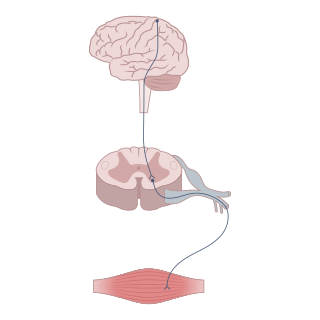

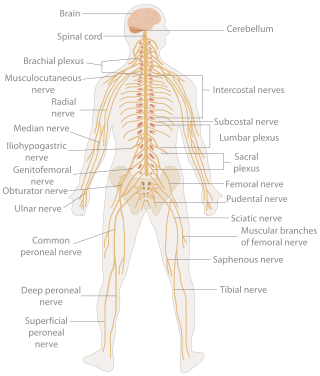

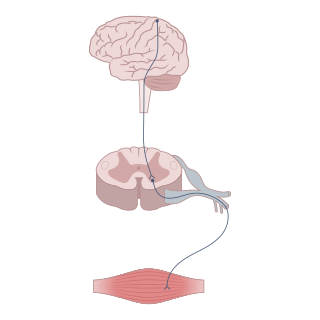

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes that impact the body, then works in tandem with the endocrine system to respond to such events. Nervous tissue first arose in wormlike organisms about 550 to 600 million years ago. In vertebrates, it consists of two main parts, the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS consists of the brain and spinal cord. The PNS consists mainly of nerves, which are enclosed bundles of the long fibers, or axons, that connect the CNS to every other part of the body. Nerves that transmit signals from the brain are called motor nerves (efferent), while those nerves that transmit information from the body to the CNS are called sensory nerves (afferent). The PNS is divided into two separate subsystems, the somatic and autonomic, nervous systems. The autonomic nervous system is further subdivided into the sympathetic, parasympathetic and enteric nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is activated in cases of emergencies to mobilize energy, while the parasympathetic nervous system is activated when organisms are in a relaxed state. The enteric nervous system functions to control the gastrointestinal system. Nerves that exit from the brain are called cranial nerves while those exiting from the spinal cord are called spinal nerves.

Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow neurons to form circuits within the central nervous system. They are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They allow the nervous system to connect to and control other systems of the body.

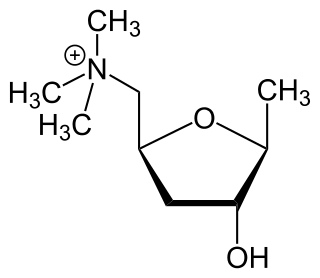

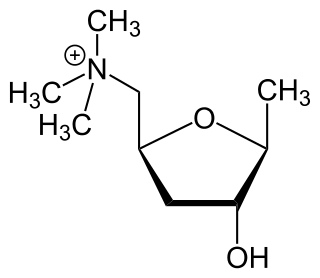

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic compound that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals as a neurotransmitter. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Parts in the body that use or are affected by acetylcholine are referred to as cholinergic.

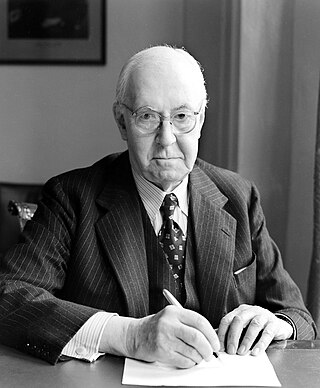

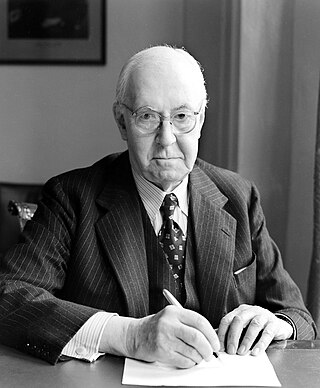

Sir Bernard Katz, FRS was a German-born British physician and biophysicist, noted for his work on nerve physiology; specifically, for his work on synaptic transmission at the nerve-muscle junction. He shared the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1970 with Julius Axelrod and Ulf von Euler. He was made a Knight Bachelor in 1969.

Sir Henry Hallett Dale was an English pharmacologist and physiologist. For his study of acetylcholine as agent in the chemical transmission of nerve pulses (neurotransmission) he shared the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Otto Loewi.

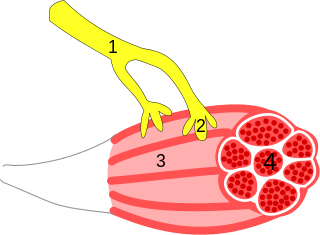

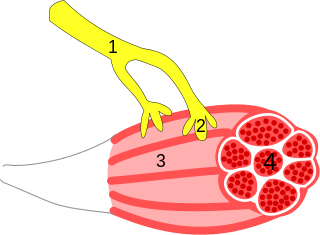

A neuroeffector junction is a site where a motor neuron releases a neurotransmitter to affect a target—non-neuronal—cell. This junction functions like a synapse. However, unlike most neurons, somatic efferent motor neurons innervate skeletal muscle, and are always excitatory. Visceral efferent neurons innervate smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands, and have the ability to be either excitatory or inhibitory in function. Neuroeffector junctions are known as neuromuscular junctions when the target cell is a muscle fiber.

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, or mAChRs, are acetylcholine receptors that form G protein-coupled receptor complexes in the cell membranes of certain neurons and other cells. They play several roles, including acting as the main end-receptor stimulated by acetylcholine released from postganglionic fibers. They are mainly found in the parasympathetic nervous system, but also have a role in the sympathetic nervous system in the control of sweat glands.

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles store various neurotransmitters that are released at the synapse. The release is regulated by a voltage-dependent calcium channel. Vesicles are essential for propagating nerve impulses between neurons and are constantly recreated by the cell. The area in the axon that holds groups of vesicles is an axon terminal or "terminal bouton". Up to 130 vesicles can be released per bouton over a ten-minute period of stimulation at 0.2 Hz. In the visual cortex of the human brain, synaptic vesicles have an average diameter of 39.5 nanometers (nm) with a standard deviation of 5.1 nm.

Renshaw cells are inhibitory interneurons found in the gray matter of the spinal cord, and are associated in two ways with an alpha motor neuron.

In molecular biology and physiology, something is GABAergic or GABAnergic if it pertains to or affects the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). For example, a synapse is GABAergic if it uses GABA as its neurotransmitter, and a GABAergic neuron produces GABA. A substance is GABAergic if it produces its effects via interactions with the GABA system, such as by stimulating or blocking neurotransmission.

An autoreceptor is a type of receptor located in the membranes of nerve cells. It serves as part of a negative feedback loop in signal transduction. It is only sensitive to the neurotransmitters or hormones released by the neuron on which the autoreceptor sits. Similarly, a heteroreceptor is sensitive to neurotransmitters and hormones that are not released by the cell on which it sits. A given receptor can act as either an autoreceptor or a heteroreceptor, depending upon the type of transmitter released by the cell on which it is embedded.

Neurotransmission is the process by which signaling molecules called neurotransmitters are released by the axon terminal of a neuron, and bind to and react with the receptors on the dendrites of another neuron a short distance away. A similar process occurs in retrograde neurotransmission, where the dendrites of the postsynaptic neuron release retrograde neurotransmitters that signal through receptors that are located on the axon terminal of the presynaptic neuron, mainly at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses.

Neuromodulation is the physiological process by which a given neuron uses one or more chemicals to regulate diverse populations of neurons. Neuromodulators typically bind to metabotropic, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) to initiate a second messenger signaling cascade that induces a broad, long-lasting signal. This modulation can last for hundreds of milliseconds to several minutes. Some of the effects of neuromodulators include altering intrinsic firing activity, increasing or decreasing voltage-dependent currents, altering synaptic efficacy, increasing bursting activity and reconfiguring synaptic connectivity.

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell. Synapses can be chemical or electrical. In case of electrical synapses, neurons are coupled bidirectionally in continuous-time to each other and are known to produce synchronous network activity in the brain. As such, signal directionality cannot always be defined across electrical synapses.

Axon terminals are distal terminations of the branches of an axon. An axon, also called a nerve fiber, is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell that conducts electrical impulses called action potentials away from the neuron's cell body to transmit those impulses to other neurons, muscle cells, or glands. Most presynaptic terminals in the central nervous system are formed along the axons, not at their ends.

A false neurotransmitter is a chemical compound which closely imitates the action of a neurotransmitter in the nervous system. Examples include 5-MeO-αMT and α-methyldopa. Another compound that has been discussed as a possible false neurotransmitter is octopamine.

David Sulzer is an American neuroscientist and musician. He is a professor at Columbia University Medical Center in the departments of psychiatry, neurology, and pharmacology. Sulzer's laboratory investigates the interaction between the synapses of the cerebral cortex and the basal ganglia, including the dopamine system, in habit formation, planning, decision making, and diseases of the system. His lab has developed the first means to optically measure neurotransmission, and has introduced new hypotheses of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease, and changes in synapses that produce autism and habit learning.

Victor Percy Whittaker was a British biochemist who pioneered studies on the subcellular fractionation of the brain. He did this by isolating synaptosomes and synaptic vesicles from the mammalian brain and demonstrating that synaptic vesicles store the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.