Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. The decision partially overruled the Court's 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which had held that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that had come to be known as "separate but equal". The Court's unanimous decision in Brown, and its related cases, paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the civil rights movement, and a model for many future impact litigation cases.

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact on the settlement patterns of various groups. This is most commonly used in reference to the United States. Desegregation was long a focus of the American civil rights movement, both before and after the US Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education, particularly desegregation of the school systems and the military. Racial integration of society was a closely related goal.

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974), was a significant United States Supreme Court case dealing with the planned desegregation busing of public school students across district lines among 53 school districts in metropolitan Detroit. It concerned the plans to integrate public schools in the United States following the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision.

Lloyd Lionel Gaines was the plaintiff in Gaines v. Canada (1938), one of the most important early court cases in the 20th-century U.S. civil rights movement. After being denied admission to the University of Missouri School of Law because he was African American, and refusing the university's offer to pay for him to attend a neighboring state's law school that had no racial restriction, Gaines filed suit. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ruled in his favor, holding that the separate but equal doctrine required that Missouri either admit him or set up a separate law school for black students.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is an American civil rights organization and law firm based in New York City.

Sundown towns, also known as sunset towns, gray towns, or sundowner towns, are all-white municipalities or neighborhoods in the United States and Canada that were most prevalent before the mid-20th century, which practiced a form of racial segregation by excluding non-whites via some combination of discriminatory local laws, intimidation or violence. The term came into use because of signs that directed "colored people" to leave town by sundown.

This is a timeline of African-American history, the part of history that deals with African Americans.

Facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation have been systematically separated in the United States based on racial categorizations. Segregation was the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites, as well as the separation of other ethnic minorities from majority and mainstream communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage, and the separation of roles within an institution. The U.S. Armed Forces were formally segregated until 1948, as black units were separated from white units but were still typically led by white officers.

Marie Frankie Muse Freeman was an American civil rights attorney, and the first woman to be appointed to the United States Commission on Civil Rights (1964–79), a federal fact-finding body that investigates complaints alleging discrimination. Freeman was instrumental in creating the Citizens' Commission on Civil Rights founded in 1982. She was a practicing attorney in State and Federal courts for nearly sixty years.

The Gautreaux Project is a US housing-desegregation project initiated by court order. It is notable both for being one of the only social programs based in a randomized experiment, and the only anti-poverty housing program endorsed by the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton administrations.

Rubey Mosley Hulen was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri. In July 1950, Hulen issued an injunction requiring the City of St. Louis, Missouri to open its fairgrounds and Marquette swimming pools to swimmers of all races.

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case that held that racially restrictive housing covenants cannot legally be enforced.

Morgan v. Hennigan was the case that defined the school busing controversy in Boston, Massachusetts during the 1970s. On March 14, 1972, the Boston chapter of the NAACP filed a class action lawsuit against the Boston School Committee on behalf of 14 black parents and 44 children. Tallulah Morgan headed the list of plaintiffs, and James Hennigan, then chair of the School Committee, was listed as the main defendant.

Hocutt v. Wilson, N.C. Super. Ct. (1933) (unreported), was the first attempt to desegregate higher education in the United States. It was initiated by two African American lawyers from Durham, North Carolina, Conrad O. Pearson and Cecil McCoy, with the support of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The case was ultimately dismissed for lack of standing, but it served as a test case for challenging the "separate but equal" doctrine in education and was a precursor to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

School segregation in the United States was the segregation of students based on their ethnicity. While not prohibited from having schools, various minorities were barred from most schools, schools for whites. Segregation laws were dismantled in the late 1960s by the U.S. Supreme Court. Segregation continued longstanding exclusionary policies in much of the Southern United States after the Civil War. School integration in the United States took place at different times in different areas and often met resistance. Jim Crow laws codified segregation. These laws were influenced by the history of slavery and discrimination in the US. Secondary schools for African Americans in the South were called training schools instead of high schools in order to appease racist whites and focused on vocational education. After the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, which banned segregated school laws, school segregation took de facto form. School segregation declined rapidly during the late 1960s and early 1970s as the government became strict on schools' plans to combat segregation more effectively as a result of Green v. County School Board of New Kent County. Voluntary segregation by income appears to have increased since 1990. Racial segregation has either increased or stayed constant since 1990, depending on which definition of segregation is used. In general, definitions based on the amount of interaction between black and white students show increased racial segregation, while definitions based on the proportion of black and white students in different schools show racial segregation remaining approximately constant.

The Delmar Divide refers to Delmar Boulevard as a socioeconomic and racial dividing line in St. Louis, Missouri. The term was popularized outside Greater St. Louis by a four-minute documentary from the BBC. Delmar Blvd. is an east–west street with its western terminus in the municipality of Olivette, Missouri extending into the City of St. Louis. There is a dense concentration of eclectic commerce on Delmar Blvd. near the municipal borders of University City and St. Louis. This area is known as the Delmar Loop. Delmar Blvd. is referred to as a “divide” in reference to the dramatic difference in racial populations in the neighborhoods to its immediate north and south: as of 2012, residents south of Delmar are 73% white, while residents north of Delmar are 98% black, and because of corresponding distinct socioeconomic, cultural, and public policy differences.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

George T. Raymond was an American civil rights leader from Pennsylvania who served as president of the Chester, Pennsylvania, branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1942 to 1977. He was integral in the desegregation of businesses, public housing and schools in Chester and co-led the Chester school protests in 1964 which made Chester a key battleground in the civil rights movement.

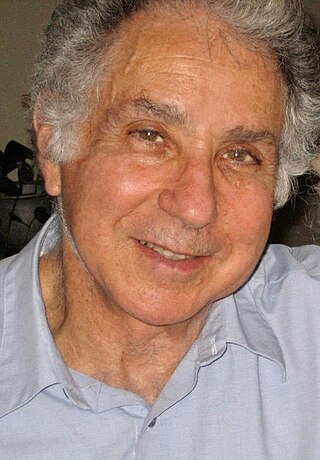

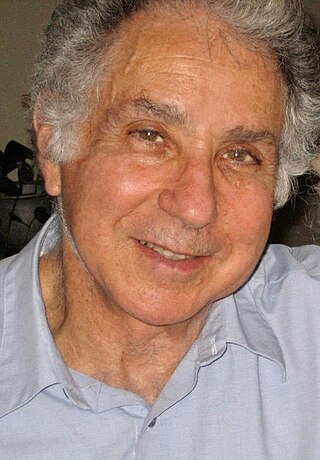

Lewis M. Steel is an American civil rights attorney and author who was co-lead counsel of the legal team that freed the boxer Rubin Carter and John Artis after they were wrongly convicted of murder. While working for the NAACP during the 1960s, he worked to desegregate public schools in the North. In 1971 he joined other civil rights lawyers, including William Kunstler, and New York Times columnist Tom Wicker, to negotiate a settlement of the Attica Prison riot. He was the lead attorney in Avagliano v. Sumitomo Shoji America, 457 U.S. 176 (1982) which established that American subsidiaries of foreign corporations must obey American civil rights laws. He works as a civil rights attorney at the New York law firm Outten & Golden LLP.