Related Research Articles

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, or simply the Ilinden Uprising, of August–October 1903, was an organized revolt against the Ottoman Empire, which was prepared and carried out by the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization, with the support of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee, which included mostly Bulgarian military personnel. The name of the uprising refers to Ilinden, a name for Elijah's day, and to Preobrazhenie which means Feast of the Transfiguration. Some historians describe the rebellion in the Serres revolutionary district as a separate uprising, calling it the Krastovden Uprising, because on September 14 the revolutionaries there also rebelled. The revolt lasted from the beginning of August to the end of October and covered a vast territory from the western Black Sea coast in the east to the shores of Lake Ohrid in the west.

Georgi Nikolov Delchev, known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev, was an important Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji), active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions, as well as in Bulgaria, at the turn of the 20th century. He was the most prominent leader of what is known today as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a secret revolutionary society that was active in Ottoman territories in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Delchev was its representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria. As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), participating in the work of its governing body. He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Krste Petkov Misirkov was a philologist, journalist, historian and ethnographer from the region of Macedonia.

Damyan Yovanov Gruev was а Bulgarian teacher, revolutionary and insurgent leader in the Ottoman regions of Macedonia and Thrace. He was one of the six founders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.

Gyorche Petrov Nikolov born Georgi Petrov Nikolov, was a Bulgarian teacher and revolutionary, one of the leaders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). He was its representative in Sofia, the capital of Principality of Bulgaria. As such he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), participating in the work of its governing body. During the Balkan Wars, Petrov was a Bulgarian army volunteer, and during the First World War, he was involved in the activity of the Bulgarian occupation authorities in Serbia and Greece. Subsequently, he participated in Bulgarian politics, but was eventually killed by the rivaling IMRO right-wing faction. According to the Macedonian historiography, he was an ethnic Macedonian.

Todor Aleksandrov Poporushov, best known as Todor Alexandrov, also spelt as Alexandroff, was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary, Bulgarian army officer, politician and teacher. He favored initially the annexation of Macedonia to Bulgaria, but later switched to the idea of an Independent Macedonia as a second Bulgarian state on the Balkans. Alexandrov was a member of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organisation (IMARO) and later of the Central Committee of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO).

Yane Sandanski was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary. He is recognized as a national hero in both Bulgaria and North Macedonia.

Petar Poparsov or Petar Pop Arsov was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary, educator and one of the founders of the Internal Macedonian Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO). He is regarded as an ethnic Macedonian by the historiography in North Macedonia.

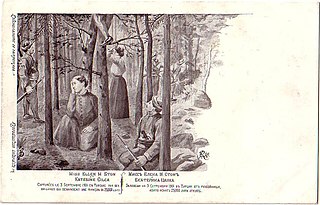

The Miss Stone Affair was the kidnapping of American Protestant missionary Ellen Maria Stone and her pregnant Bulgarian fellow missionary and friend Katerina Cilka by the pro-Bulgarian Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.

Ivan Naumov, nicknamed Alyabaka or Alyabako was a Bulgarian revolutionary, a member of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO).

Lazar Poptraykov was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji). He was also a Bulgarian Exarchate teacher and poet from Ottoman Macedonia. He was one of the leaders of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) in the region of Kastoria (Kostur) during the Ilinden Uprising. Despite his Bulgarian identification, per the post-WWII Macedonian historiography he is considered as an ethnic Macedonian.

Independent Macedonia was a conceptual project of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) to create an independent Macedonia, during the interwar period.

Svoboda ili smart was a revolutionary slogan used during the national-liberation struggles by the Bulgarian revolutionaries, called comitadjis. The slogan was in use during the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries.

Macedonia for the Macedonians is a slogan and political concept used during the first half of the 20th century in the region of Macedonia. It aimed to encompass all the nationalities in the area, into a separate supranational entity.

Autonomy for the region of Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace within the Ottoman Empire was a concept that arose in the late 19th century and was popular until ca. 1920. The plan was developed among Macedonian and Thracian Bulgarian emigres in Sofia and covered several meanings. Serbia and Greece were totally opposed to that set of ideas while Bulgaria was ambivalent to them. In fact Sofia advocated granting such autonomy as a prelude to the annexation of both areas, as for many Bulgarian emigres it was seen in the same way.

Katerina Cilka was a Bulgarian Protestant missionary from Bansko, abducted for ransom by a detachment of the pro-Bulgarian Inner Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) in 1901 and released in 1902.

The Macedonian-Adrianople Social Democratic Group was a regional faction of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party in the Ottoman Empire. According to Macedonian historians, most of its activists were ethnic Macedonians.

Due to the lack of original protocol documentation, and the fact its early organic statutes were not dated, the first statute of the clandestine Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) is uncertain and is a subject to dispute among researchers. The dispute also includes its first name and ethnic character, as well as the authenticity, dating, validity, and authorship of its supposed first statute. Certain contradictions and even mutually exclusive statements, along with inconsistencies exist in the testimonies of the founding and other early members of the Organization, which further complicates the solution of the problem. It is not yet clear whether the earliest statutory documents of the Organization have been discovered. Its earliest basic documents discovered for now, became known to the historical community during the early 1960s.

Dobri Daskalov was a Bulgarian revolutionary, member and voivode of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. In today North Macedonia, he is regarded an Ethnic Macedonian.

References

- ↑ Празник во служба на големобугарската идеја, Група првоборци и преродбеници, Утрински весник, Број 2228 среда, 08 ноември 2006.

- ↑ Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1-85065-534-0, p. 53.

- ↑ Димитар Димитров, Од „Сѐ за Македонија" - до „Сѐ од Македонија". Deutsche Welle, 25.10.202325 октомври 2023.

- ↑ Its first name was "Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees", which was later changed several times. IMRO was active not only in Macedonia but also in Thrace (the Vilayet of Adrianople). Since its early name emphasized the Bulgarian nature of the organization by linking the inhabitants of Thrace and Macedonia to Bulgaria, these facts are still difficult to be explained from the Macedonian historiography. They suggest that IMRO revolutionaries in the Ottoman period did not differentiate between ‘Macedonians’ and ‘Bulgarians’. Moreover, as their own writings attest, they often saw themselves and their compatriots as ‘Bulgarians’. All of them wrote in standard Bulgarian language. For more see: Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004) Historiography, Myths and the Nation in the Republic of Macedonia. In: Brunnbauer, Ulf, (ed.) (Re)Writing History. Historiography in Southeast Europe after Socialism. Studies on South East Europe, vol. 4. LIT, Münster, pp. 165-200 ISBN 382587365X.382587365X.

- ↑ Tschavdar Marinov, We the Macedonians, The Paths of Macedonian Supra-Nationalism (1878–1912), in "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe" with Mishkova Diana as ed., Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, pp. 107-137.

- ↑ Contrary to the assertions of Skopje's historiography, Macedonian revolutionaries clearly manifested Bulgarian national identity. Their Macedonian autonomism and “separatism” represented a strictly supranational project, not national. Entangled Histories of the Balkans:, Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, p. 303.

- ↑ There is, moreover, the not less complicated issue of what autonomy meant to the people who espoused it in their writings. According to Hristo Tatarchev, their demand for autonomy was motivated not by an attachment to Macedonian national identity but out of concern that an explicit agenda of unification with Bulgaria would provoke other small Balkan nations and the Great Powers to action. Macedonian autonomy, in other words, can be seen as a tactical diversion, or as “Plan B” of Bulgarian unification. İpek Yosmaoğlu, Blood Ties: Religion, Violence and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908, Cornell University Press, 2013, ISBN 0801469791, pp. 15-16.