Related Research Articles

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dimensional structural configuration. In contrast to genetics, which refers to the study of individual genes and their roles in inheritance, genomics aims at the collective characterization and quantification of all of an organism's genes, their interrelations and influence on the organism. Genes may direct the production of proteins with the assistance of enzymes and messenger molecules. In turn, proteins make up body structures such as organs and tissues as well as control chemical reactions and carry signals between cells. Genomics also involves the sequencing and analysis of genomes through uses of high throughput DNA sequencing and bioinformatics to assemble and analyze the function and structure of entire genomes. Advances in genomics have triggered a revolution in discovery-based research and systems biology to facilitate understanding of even the most complex biological systems such as the brain.

Cyanobacteria, also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name cyanobacteria refers to their color, which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blue-green algae, although they are not usually scientifically classified as algae. They appear to have originated in a freshwater or terrestrial environment. Sericytochromatia, the proposed name of the paraphyletic and most basal group, is the ancestor of both the non-photosynthetic group Melainabacteria and the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, also called Oxyphotobacteria.

Prochlorococcus is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation. These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosynthetic organism on Earth. Prochlorococcus microbes are among the major primary producers in the ocean, responsible for a large percentage of the photosynthetic production of oxygen. Prochlorococcus strains, called ecotypes, have physiological differences enabling them to exploit different ecological niches. Analysis of the genome sequences of Prochlorococcus strains show that 1,273 genes are common to all strains, and the average genome size is about 2,000 genes. In contrast, eukaryotic algae have over 10,000 genes.

Carboxysomes are bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) consisting of polyhedral protein shells filled with the enzymes ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO)—the predominant enzyme in carbon fixation and the rate limiting enzyme in the Calvin cycle—and carbonic anhydrase.

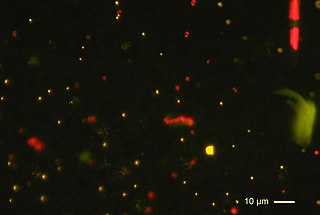

Photosynthetic picoplankton or picophytoplankton is the fraction of the phytoplankton performing photosynthesis composed of cells between 0.2 and 2 µm in size (picoplankton). It is especially important in the central oligotrophic regions of the world oceans that have very low concentration of nutrients.

Sallie Watson "Penny" Chisholm is an American biological oceanographer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She is an expert in the ecology and evolution of ocean microbes. Her research focuses particularly on the most abundant marine phytoplankton, Prochlorococcus, that she discovered in the 1980s with Rob Olson and other collaborators. She has a TED talk about their discovery and importance called "The tiny creature that secretly powers the planet".

Synechococcus is a unicellular cyanobacterium that is very widespread in the marine environment. Its size varies from 0.8 to 1.5 µm. The photosynthetic coccoid cells are preferentially found in well–lit surface waters where it can be very abundant. Many freshwater species of Synechococcus have also been described.

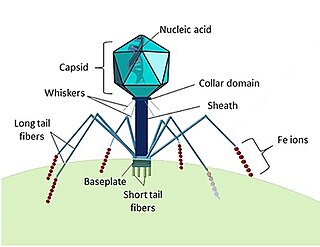

Cyanophages are viruses that infect cyanobacteria, also known as Cyanophyta or blue-green algae. Cyanobacteria are a phylum of bacteria that obtain their energy through the process of photosynthesis. Although cyanobacteria metabolize photoautotrophically like eukaryotic plants, they have prokaryotic cell structure. Cyanophages can be found in both freshwater and marine environments. Marine and freshwater cyanophages have icosahedral heads, which contain double-stranded DNA, attached to a tail by connector proteins. The size of the head and tail vary among species of cyanophages. Cyanophages infect a wide range of cyanobacteria and are key regulators of the cyanobacterial populations in aquatic environments, and may aid in the prevention of cyanobacterial blooms in freshwater and marine ecosystems. These blooms can pose a danger to humans and other animals, particularly in eutrophic freshwater lakes. Infection by these viruses is highly prevalent in cells belonging to Synechococcus spp. in marine environments, where up to 5% of cells belonging to marine cyanobacterial cells have been reported to contain mature phage particles.

Photosynthetic reaction centre proteins are main protein components of photosynthetic reaction centres (RCs) of bacteria and plants. They are transmembrane proteins embedded in the chloroplast thylakoid or bacterial cell membrane.

Paulinella is a genus of at least eleven species including both freshwater and marine amoeboids.

Bacterioplankton refers to the bacterial component of the plankton that drifts in the water column. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word πλανκτος, meaning "wanderer" or "drifter", and bacterium, a Latin term coined in the 19th century by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg. They are found in both seawater and freshwater.

The manA RNA motif refers to a conserved RNA structure that was identified by bioinformatics. Instances of the manA RNA motif were detected in bacteria in the genus Photobacterium and phages that infect certain kinds of cyanobacteria. However, most predicted manA RNA sequences are derived from DNA collected from uncultivated marine bacteria. Almost all manA RNAs are positioned such that they might be in the 5' untranslated regions of protein-coding genes, and therefore it was hypothesized that manA RNAs function as cis-regulatory elements. Given the relative complexity of their secondary structure, and their hypothesized cis-regulatory role, they might be riboswitches.

The wcaG RNA motif is an RNA structure conserved in some bacteria that was detected by bioinformatics. wcaG RNAs are found in certain phages that infect cyanobacteria. Most known wcaG RNAs were found in sequences of DNA extracted from uncultivated marine bacteria. wcaG RNAs might function as cis-regulatory elements, in view of their consistent location in the possible 5' untranslated regions of genes. It was suggested the wcaG RNAs might further function as riboswitches.

Marine microorganisms are defined by their habitat as microorganisms living in a marine environment, that is, in the saltwater of a sea or ocean or the brackish water of a coastal estuary. A microorganism is any microscopic living organism or virus, that is too small to see with the unaided human eye without magnification. Microorganisms are very diverse. They can be single-celled or multicellular and include bacteria, archaea, viruses and most protozoa, as well as some fungi, algae, and animals, such as rotifers and copepods. Many macroscopic animals and plants have microscopic juvenile stages. Some microbiologists also classify biologically active entities such as viruses and viroids as microorganisms, but others consider these as non-living.

In molecular biology, Cyanobacterial non-coding RNAs are non-coding RNAs which have been identified in species of cyanobacteria. Large scale screens have identified 21 Yfr in the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus and related species such as Synechococcus. These include the Yfr1 and Yfr2 RNAs. In Prochlorococcus and Synechocystis, non-coding RNAs have been shown to regulate gene expression. NsiR4, widely conserved throughout the cyanobacterial phylum, has been shown to be involved in nitrogen assimilation control in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and in the filamentous, nitrogen-fixing Anabaena sp. PCC 7120.

KaiB is a gene located in the highly-conserved kaiABC gene cluster of various cyanobacterial species. Along with KaiA and KaiC, KaiB plays a central role in operation of the cyanobacterial circadian clock. Discovery of the Kai genes marked the first-ever identification of a circadian oscillator in a prokaryotic species. Moreover, characterization of the cyanobacterial clock demonstrated the existence of transcription-independent, post-translational mechanisms of rhythm generation, challenging the universality of the transcription-translation feedback loop model of circadian rhythmicity.

Auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) are found in many bacteriophages but originated in bacterial cells. AMGs modulate host cell metabolism during infection so that the phage can replicate more efficiently. For instance, bacteriophages that infect the abundant marine cyanobacteria Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus (cyanophages) carry AMGs that have been acquired from their immediate host as well as more distantly-related bacteria. Cyanophage AMGs support a variety of functions including photosynthesis, carbon metabolism, nucleic acid synthesis and metabolism.

Genomic streamlining is a theory in evolutionary biology and microbial ecology that suggests that there is a reproductive benefit to prokaryotes having a smaller genome size with less non-coding DNA and fewer non-essential genes. There is a lot of variation in prokaryotic genome size, with the smallest free-living cell's genome being roughly ten times smaller than the largest prokaryote. Two of the bacterial taxa with the smallest genomes are Prochlorococcus and Pelagibacter ubique, both highly abundant marine bacteria commonly found in oligotrophic regions. Similar reduced genomes have been found in uncultured marine bacteria, suggesting that genomic streamlining is a common feature of bacterioplankton. This theory is typically used with reference to free-living organisms in oligotrophic environments.

Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as viruses that are found in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. Viruses are small infectious agents that can only replicate inside the living cells of a host organism, because they need the replication machinery of the host to do so. They can infect all types of life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Marine prokaryotes are marine bacteria and marine archaea. They are defined by their habitat as prokaryotes that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. All cellular life forms can be divided into prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells have a nucleus enclosed within membranes, whereas prokaryotes are the organisms that do not have a nucleus enclosed within a membrane. The three-domain system of classifying life adds another division: the prokaryotes are divided into two domains of life, the microscopic bacteria and the microscopic archaea, while everything else, the eukaryotes, become the third domain.

References

- 1 2 Neistat, Aimee (15 February 2008). "Scientist from down under makes waves". Jerusalem Post. p. 16.

- 1 2 "Debbie Lindell". Simons Foundation. 5 October 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ Lindell, Debbie; Post, Anton F. (1995). "Ultraphytoplankton succession is triggered by deep winter mixing in the Gulf of Aqaba (Eilat), Red Sea". Limnology and Oceanography. 40 (6): 1130–1141. Bibcode:1995LimOc..40.1130L. doi:10.4319/lo.1995.40.6.1130. ISSN 0024-3590.

- ↑ Lindell, Debbie; Post, Anton F. (2001). "Ecological Aspects of ntcA Gene Expression and Its Use as an Indicator of the Nitrogen Status of Marine Synechococcus spp". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 67 (8): 3340–3349. Bibcode:2001ApEnM..67.3340L. doi:10.1128/aem.67.8.3340-3349.2001. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 93026 . PMID 11472902.

- ↑ Lindell, Debbie; Padan, Etana; Post, Anton F. (1998). "Regulation of ntcA Expression and Nitrite Uptake in the Marine Synechococcus sp. Strain WH 7803". Journal of Bacteriology. 180 (7): 1878–1886. doi:10.1128/jb.180.7.1878-1886.1998. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 107103 . PMID 9537388.

- ↑ Lindell, Debbie; Jaffe, Jacob D.; Johnson, Zackary I.; Church, George M.; Chisholm, Sallie W. (2005). "Photosynthesis genes in marine viruses yield proteins during host infection". Nature. 438 (7064): 86–89. Bibcode:2005Natur.438...86L. doi:10.1038/nature04111. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16222247. S2CID 4347406.

- ↑ Lindell, Debbie; Sullivan, Matthew B.; Johnson, Zackary I.; Tolonen, Andrew C.; Rohwer, Forest; Chisholm, Sallie W. (2004). "Transfer of photosynthesis genes to and from Prochlorococcus viruses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (30): 11013–11018. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111013L. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401526101 . ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 503735 . PMID 15256601.

- ↑ Lindell, Debbie; Jaffe, Jacob D.; Coleman, Maureen L.; Futschik, Matthias E.; Axmann, Ilka M.; Rector, Trent; Kettler, Gregory; Sullivan, Matthew B.; Steen, Robert; Hess, Wolfgang R.; Church, George M. (2007). "Genome-wide expression dynamics of a marine virus and host reveal features of co-evolution". Nature. 449 (7158): 83–86. Bibcode:2007Natur.449...83L. doi:10.1038/nature06130. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17805294. S2CID 4412265.

- ↑ Siegel-Itzkovich, Judy (14 October 2007). "Host-virus relations can be a win-win situation". Jerusalem Post. p. 6.

- ↑ Avrani, Sarit; Wurtzel, Omri; Sharon, Itai; Sorek, Rotem; Lindell, Debbie (2011). "Genomic island variability facilitates Prochlorococcus–virus coexistence". Nature. 474 (7353): 604–608. doi:10.1038/nature10172. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 21720364. S2CID 205225328.

- ↑ Zborowsky, Sophia; Lindell, Debbie (5 August 2019). "Resistance in marine cyanobacteria differs against specialist and generalist cyanophages". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (34): 16899–16908. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11616899Z. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906897116 . ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6708340 . PMID 31383764.

- ↑ "Israeli Scientists Submit Patent For Self-Disinfecting, Reusable Mask". NoCamels. 25 May 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ "Debbie Lindell". scholar.google.com. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ "Debbie Lindell". Wolf Foundation. 8 January 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2022.