Related Research Articles

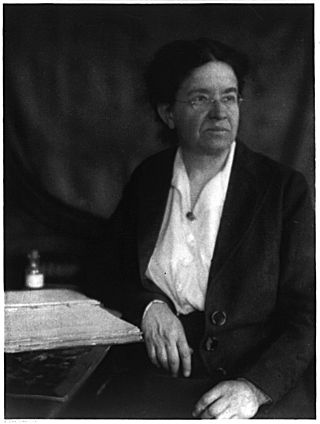

Florence Rena Sabin was an American medical scientist. She was a pioneer for women in science; she was the first woman to hold a full professorship at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences, and the first woman to head a department at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. During her years of retirement, she pursued a second career as a public health activist in Colorado, and in 1951 received the Albert Lasker Public Service Award for this work.

Livingston Farrand was an American physician, anthropologist, psychologist, public health advocate and academic administrator.

Frances Jacobs was born in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, to Jewish Bavarian immigrants and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio. She married Abraham Jacobs, the partner of her brother Jacob, and came west with him to Colorado where Wisebart and Jacobs had established businesses in Denver and Central City. In Denver, Frances Jacobs became a driving force for the city's charitable organizations and activities, with national exposure. Among the philanthropical organizations she founded, she is best remembered as a founder of the United Way and the Denver's Jewish Hospital Association.

The Colorado Medical Society (CMS) is the largest group of organized physicians in Colorado. This nonprofit organization is composed of physicians, residents and medical students. It was founded in 1871 to promote the art and science of medicine and to improve public health. Projects include a congress for health care reform, a technology fair, and lobbying for legislation to improve the health of the State's citizenry. Recent initiatives and resolutions have created electronic health projects such as COEKG.

Denver Health (hospital), formerly named Denver General Hospital, is a hospital in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Denver, founded in 1860. It is one of seven Level I Trauma Centers in Colorado. Denver Health (hospital) is one of the primary teaching hospitals in Denver and is affiliated with the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Saint Joseph Hospital is a hospital in the City Park West neighborhood of Denver.

John Laing Leal was an American physician and water treatment expert who, in 1908, was responsible for conceiving and implementing the first disinfection of a U.S. drinking water supply using chlorine. He was one of the principal expert witnesses at two trials which examined the quality of the water supply in Jersey City, New Jersey, and which evaluated the safety and utility of chlorine for production of "pure and wholesome" drinking water. The second trial verdict approved the use of chlorine to disinfect drinking water which led to an explosion of its use in water supplies across the U.S.

The town of Colorado Springs, Colorado, played an important role in the history of tuberculosis in the era before antituberculosis drugs and vaccines. Tuberculosis management before this era was difficult and often of limited effect. In the 19th century, a movement for tuberculosis treatment in hospital-like facilities called sanatoriums became prominent, especially in Europe and North America. Thus people sought tuberculosis treatment in Colorado Springs because of its dry climate and fresh mountain air. Some people stayed in boarding houses, while others sought the hospital-like facilities of sanatoriums. In the 1880s and 1890s, it is estimated that one-third of the people living in Colorado Springs had tuberculosis. The number of sanatoriums and hospitals increased into the twentieth century. During World War II, medicines were developed that successfully treated tuberculosis and by the late 1940s specialized tuberculosis treatment facilities were no longer needed.

Richard G. Buckingham was an American politician who served as the mayor of Denver, Colorado from 1876 to 1877.

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) is the principal department of the Colorado state government responsible for public health and environmental regulation.

Chinatown in Denver, Colorado, was a residential and business district of Chinese Americans in what is now the LoDo section of the city. It was also referred to as "Hop Alley", based upon a slang word for opium. The first Chinese resident of Denver, Hong Lee, arrived in 1869 and lived in a shanty at Wazee and F Streets and ran a washing and ironing laundry business. More Chinese immigrants arrived in the town the following year. Men who had worked on the construction of the first transcontinental railroad or had been miners in California crossed over the Rocky Mountains after their work was completed or mines were depleted in California.

The Baltimore City Health Department(BCHD) is the public health agency of the city of Baltimore, Maryland. BCHD convenes and collaborates with other city agencies, health care providers, community organizations and funders to "empower Baltimoreans with the knowledge, access, and environment that will enable healthy living."

Caroline Bancroft was an American journalist. She is known for the books and booklets that she wrote about Colorado's history and its pioneers. In 1990, she was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame.

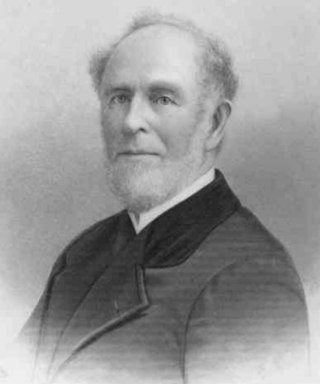

Frederick J. Bancroft was a surgeon during the American Civil War before he settled in Colorado, where he was considered to be "one of the most prominent physicians", according to a San Francisco Chronicle obituary. In the late 1870s, he and the Denver Medical Association created the public health system for Denver, Colorado to improve the health of its citizens. In 1876, Bancroft was the first president of Colorado's State Board of Health. He became Colorado Medical Society president in 1880. Bancroft was a founder and professor of the University of Denver and Colorado Seminary Medical Department in 1881.

George Atwater Jarvis was an American businessman and philanthropist. Jarvis was successful in retail and wholesale grocery, banking, and insurance industries in New York. He was founder and vice president of South Brooklyn Savings Institution and president of the Lenox Fire Insurance Company. He sat on the board or was a trustee for many organizations.

Josepha Williams Douglas (1860–1938), also commonly known as Josepha Williams, was a physician and co-operator of the Marquette-Williams Sanitarium in Denver, Colorado. She was one of the first female doctors in the state. She, as well as her mother Mary Neosho Williams, purchased a number of tracts of land in the Evergreen, Colorado area, at least some of which were ultimately donated for the Evergreen Conference District. Douglas was the daughter of Civil War General Thomas Williams and wife of Canon Charles Winfred Douglas, a plainsong musical expert and Episcopalian priest.

Mary Barker Bates (1845–1924) was a 19th-century American physician and surgeon, practicing in Salt Lake City and Colorado. She was among the first women first admitted to the Denver Medical Society. She joined the staff of the Women's and Children's Hospital in 1885. She was also a vice president of the Colorado Medical Society. Bates served on the Denver School Board.

Patricia Anne Gabow is an American academic physician, medical researcher, healthcare executive, author and lecturer. Specializing in nephrology, she joined the department of medicine, division of renal diseases, at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in 1973, advancing to a full professorship in 1987; she is presently Professor Emerita. She was the principal investigator on the National Institutes of Health Human Polycystic Kidney Disease research grant, which ran from 1985 to 1999, and defined the clinical manifestations and genetics of the disease in adults and children.

Gerald Bertram Webb was an English-born American physician who became the first president of the American Association of Immunologists, as well as president of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, National Tuberculosis Association, and Association of American Physicians.

Joseph Addison Sewall was an American physician, scientist and academic administrator who served as the first president of the University of Colorado from 1877 to 1887.

References

- ↑ "History and Mission". Denver Medical Society. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A Chronology of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Colorado Medical Societies — 1860-1899". Colorado's Healthcare Heritage. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Frederick J. Bancroft, M.D. (1834-1903)". Colorado's Healthcare Heritage: Honoring the People Who Created What We've Inherited. Colorado Healthcare History. p. 4. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Frederick J. Bancroft, M.D. (1834-1903)". Colorado's Healthcare Heritage: Honoring the People Who Created What We've Inherited. Colorado Healthcare History. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ↑ Tom Sherlock (April 2013). Colorado's Healthcare Heritage: A Chronology of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Volume One - 1800-1899. iUniverse. p. 547. ISBN 978-1-4759-8025-7.

- 1 2 3 4 "Frederick J. Bancroft, M.D. (1834-1903)". Colorado's Healthcare Heritage: Honoring the People Who Created What We've Inherited. Colorado Healthcare History. p. 2. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Frederick J. Bancroft, M.D. (1834-1903)". Colorado's Healthcare Heritage: Honoring the People Who Created What We've Inherited. Colorado Healthcare History. p. 3. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Frederick J. Bancroft, M.D. (1834-1903)". Colorado's Healthcare Heritage: Honoring the People Who Created What We've Inherited. Colorado Healthcare History. pp. 2, 3. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ↑ Tom Sherlock (April 2013). Colorado's Healthcare Heritage: A Chronology of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Volume One - 1800-1899. iUniverse. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-4759-8025-7.