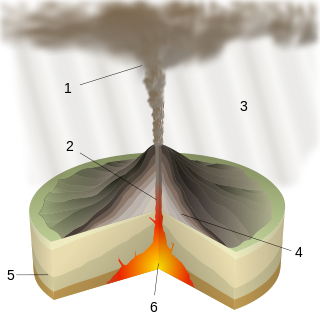

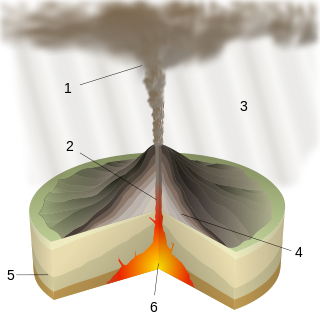

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

Mount Vesuvius is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about 9 km (5.6 mi) east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera, resulting from the collapse of an earlier, much higher structure.

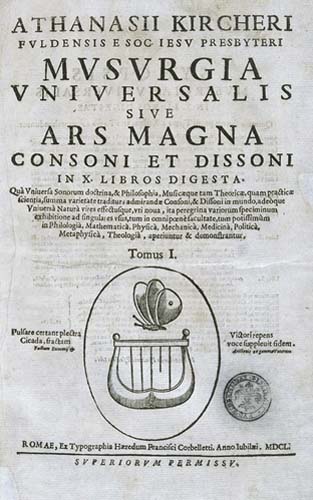

Athanasius Kircher was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jesuit Roger Joseph Boscovich and to Leonardo da Vinci for his vast range of interests, and has been honoured with the title "Master of a Hundred Arts". He taught for more than 40 years at the Roman College, where he set up a wunderkammer. A resurgence of interest in Kircher has occurred within the scholarly community in recent decades.

Volcanology is the study of volcanoes, lava, magma and related geological, geophysical and geochemical phenomena (volcanism). The term volcanology is derived from the Latin word vulcan. Vulcan was the ancient Roman god of fire.

Plinian eruptions or Vesuvian eruptions are volcanic eruptions marked by their similarity to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which destroyed the ancient Roman cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. The eruption was described in a letter written by Pliny the Younger, after the death of his uncle Pliny the Elder.

In volcanology, a Strombolian eruption is a type of volcanic eruption with relatively mild blasts, typically having a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 1 or 2. Strombolian eruptions consist of ejection of incandescent cinders, lapilli, and volcanic bombs, to altitudes of tens to a few hundreds of metres. The eruptions are small to medium in volume, with sporadic violence. This type of eruption is named for the Italian volcano Stromboli.

Several types of volcanic eruptions—during which material is expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure—have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are often named after famous volcanoes where that type of behavior has been observed. Some volcanoes may exhibit only one characteristic type of eruption during a period of activity, while others may display an entire sequence of types all in one eruptive series.

Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was printed in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria. It was a compendium of ancient and contemporary thinking about music, its production and its effects. It explored, in particular, the relationship between the mathematical properties of music with health and rhetoric. The work complements two of Kircher's other books: Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica had set out the secret underlying coherence of the universe and Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae had explored the ways of knowledge and enlightenment. What Musurgia Universalis contained, through its exploration of dissonance within harmony, was an explanation of the presence of evil in the world.

Of the many eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, a major stratovolcano in southern Italy, the best-known is its eruption in 79 AD, which was one of the deadliest in history.

Mundus subterraneus, quo universae denique naturae divitiae is a scientific textbook written by Athanasius Kircher, and published in 1665. The work depicts Earth's geography through textual description, as well as lavish illustrations.

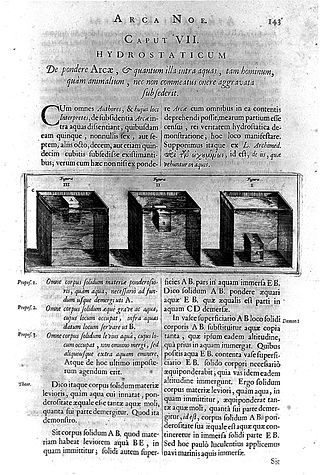

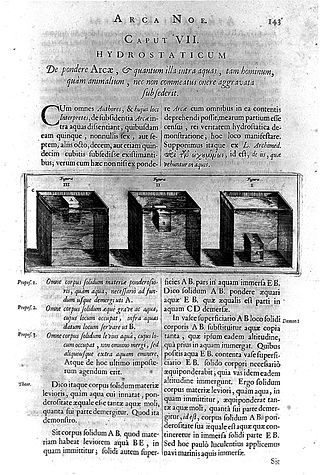

Arca Noë is a book published in 1675 by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It is a study of the biblical story of Noah's Ark, published by the cartographer and bookseller Johannes van Waesbergen in Amsterdam. Kircher's aim in Arca Noë was to reconcile recent discoveries in nature and geography with the text of the Bible. This demonstration of the underlying unity and truth between revelation and science was a fundamental task of Catholic scholarship at the time. Together with its sister volume Turris Babel, Arca Noë presented a complete intellectual project to demonstrate how contemporary science supported the account of the Book of Genesis.

Ars Magnesia was a book on magnetism by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in 1631. It was his first published work, written while he was professor of ethics and mathematics, Hebrew and Syriac at the University of Würzburg. It was published in Würzburg by Elias Michael Zink.

Polygraphia nova et universalis ex combinatoria arte directa is a 1663 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was one of Kircher's most highly regarded works and his only complete work on the subject of cryptography, although he made passing references to the topic elsewhere. The book was distributed as a private gift to selected European rulers, some of who also received an arca steganographica, a presentation chest containing wooden tallies used to encrypt and decrypt codes.

Scrutinium Physico-Medicum Contagiosae Luis, Quae Pestis Dicitur is a 1658 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, containing his observations and theories about the bubonic plague that struck Rome in the summer of 1656. Kircher was the first person to view infected blood through a microscope, and his observations are described in the book. The work was printed on the presses of Vitale Mascardi and dedicated to Pope Alexander VII.

Obeliscus Pamphilius is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was published in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Pope Innocent X in his jubilee year. The subject of the work was Kircher's attempt to translate the hieroglyphs on the sides of an obelisk erected in the Piazza Navona.

Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica is a 1641 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Emperor Ferdinand III and printed in Rome by Hermann Scheuss. It developed the ideas set out in his earlier Ars Magnesia and argued that the universe is governed by universal physical forces of attraction and repulsion. These were, as described in the motto in the book's first illustration, 'hidden nodes' of connection. The force that drew things together in the physical world was, he argued, the same force that drew people's souls towards God. The work is divided into three books: 1.De natura et facultatibus magnetis, 2.Magnes applicatus, 3.Mundus sive catena magnetica. It is noted for the first use of the term 'electromagnetism'.

Pantometrum Kircherianum is a 1660 work by the Jesuit scholars Gaspar Schott and Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Christian Louis I, Duke of Mecklenburg and printed in Würzburg by Johann Gottfried Schönwetter. It was a description, with building instructions, of a measuring device called the pantometer, that Kircher had developed some years before. The first edition include 32 copperplate illustrations.

Arithmologia, sive De Abditis Numerorum Mysteriis is a 1665 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was published by Varese, the main printing house for the Jesuit order in Rome in the mid-17th century. It was dedicated to Franz III. Nádasdy, a convert to Catholicism to whom Kircher had previously co-dedicated Oedipus Aegyptiacus. Arithmologia is the only one of Kircher's works devoted entirely to different aspects of number symbolism.

Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae is a 1646 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans and published in Rome by Lodovico Grignani. A second edition was published in Amsterdam in 1671 by Johann Jansson. Ars Magna was the first description published in Europe of the illumination and projection of images. The book contains the first printed illustration of Saturn and the 1671 edition also contained a description of the magic lantern.

The Kircherian Museum was a public collection of antiquities and artifacts, a cabinet of curiosities, founded in 1651 by the Jesuit father Athanasius Kircher in the Roman College. Considered the first museum in the world, its collections were gradually dispersed over the centuries under different curatorships. After the Unification of Italy, the museum was dissolved in 1916 and its collection was granted to various other Roman and regional museums.