The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences. Osiris's murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris's wife Isis restores her husband's body, allowing him to posthumously conceive their son, Horus. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set's rival for the throne. Their often violent conflict ends with Horus's triumph, which restores maat to Egypt after Set's unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris's resurrection.

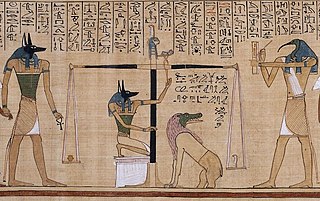

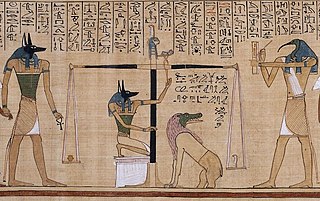

Ammit was an ancient Egyptian goddess with the forequarters of a lion, the hindquarters of a hippopotamus, and the head of a crocodile—the three largest "man-eating" animals known to ancient Egyptians. In ancient Egyptian religion, Ammit played an important role during the funerary ritual, the Judgment of the Dead.

The ancient Egyptians believed that a soul was made up of many parts. In addition to these components of the soul, there was the human body.

The Book of the Dead is the name given to an ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom to around 50 BC. "Book" is the closest term to describe the loose collection of texts consisting of a number of magic spells intended to assist a dead person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife and written by many priests over a period of about 1,000 years. In 1842, the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius introduced for these texts the German name Todtenbuch, translated to English as 'Book of the Dead'. The original Egyptian name for the text, transliterated rw nw prt m hrw, is translated as Spells of Coming Forth by Day.

The Book of Abraham is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, first published in 1842 by Joseph Smith. Smith said the book was a translation from several Egyptian scrolls discovered in the early 19th century during an archeological expedition by Antonio Lebolo, and purchased by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from a traveling mummy exhibition on July 3, 1835. According to Smith, the book was "a translation of some ancient records... purporting to be the writings of Abraham, while he was in Egypt, called the Book of Abraham, written by his own hand, upon papyrus". The Book of Abraham is about Abraham's early life, his travels to Canaan and Egypt, and his vision of the cosmos and its creation.

The Westcar Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian text containing five stories about miracles performed by priests and magicians. In the papyrus text, each of these tales are told at the royal court of king Khufu (Cheops) by his sons. The story in the papyrus usually is rendered in English as, "King Cheops and the Magicians" and "The Tale of King Cheops' Court". In German, into which the text of the Westcar Papyrus was first translated, it is rendered as Die Märchen des Papyrus Westcar.

The Coffin Texts are a collection of ancient Egyptian funerary spells written on coffins beginning in the First Intermediate Period. They are partially derived from the earlier Pyramid Texts, reserved for royal use only, but contain substantial new material related to everyday desires, indicating a new target audience of common people. Coffin texts are dated back to 2100 BCE. Ordinary Egyptians who could afford a coffin had access to these funerary spells and the pharaoh no longer had exclusive rights to an afterlife.

The opening of the mouth ceremony was an ancient Egyptian ritual described in funerary texts such as the Pyramid Texts. From the Old Kingdom to the Roman Period, there is ample evidence of this ceremony, which was believed to give the deceased their fundamental senses to carry out tasks in the afterlife. Various practices were conducted on the corpse, including the use of specific instruments to touch body parts like the mouth and eyes. These customs were often linked with childbirth, which denoted rebirth and new beginnings. For instance, cutting bloody meat from animals as offerings for the deceased signified the birthing process, which typically involves blood, and represented the commencement of a new life. Additionally, tools like the peseshkef, which resembled the tail of a fish and were originally employed for cutting infants' umbilical cords, further emphasized the idea of "rebirth".

The literature that makes up the ancient Egyptian funerary texts is a collection of religious documents that were used in ancient Egypt, usually to help the spirit of the concerned person to be preserved in the afterlife.

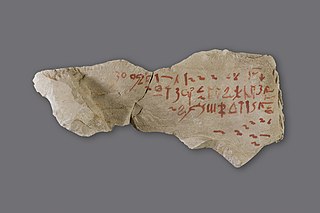

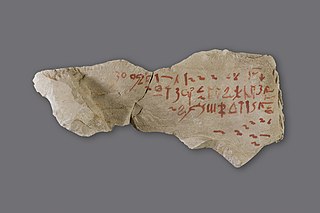

Ancient literature comprises religious and scientific documents, tales, poetry and plays, royal edicts and declarations, and other forms of writing that were recorded on a variety of media, including stone, clay tablets, papyri, palm leaves, and metal. Before the spread of writing, oral literature did not always survive well, but some texts and fragments have persisted. An unknown number of written works have not survived the ravages of time and are therefore lost.

Instruction of Amenemope is a literary work composed in Ancient Egypt, most likely during the Ramesside Period ; it contains thirty chapters of advice for successful living, ostensibly written by the scribe Amenemope son of Kanakht as a legacy for his son. A characteristic product of the New Kingdom "Age of Personal Piety", the work reflects on the inner qualities, attitudes, and behaviors required for a happy life in the face of increasingly difficult social and economic circumstances. It is widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of ancient near-eastern wisdom literature and has been of particular interest to modern scholars because of its similarity to the later biblical Book of Proverbs.

Sebayt is the ancient Egyptian term for a genre of pharaonic literature. sbꜣyt literally means "teachings" or "instructions" and refers to formally written ethical teachings focused on the "way of living truly". Sebayt is considered an Egyptian form of wisdom literature.

The Satire of the Trades, also called The Instruction of Kheti, is a didactic work of ancient Egyptian literature. It takes the form of an instruction and was composed by a scribe from Sile named Kheti for his son Pepi. The Satire exalts the career of a scribe while remarking on the drudgery experienced in other professions. Laborers are described in the document as having tired arms and to be living in subpar conditions. This poor standard of living is juxtaposed with the life of a scribe, whose job is "greater than any profession". Egyptologists disagree on whether or not the text is satirical. The same Kheti may have composed the Instructions of Amenemhat, but this is unclear.

Ancient Egyptian literature was written with the Egyptian language from ancient Egypt's pharaonic period until the end of Roman domination. It represents the oldest corpus of Egyptian literature. Along with Sumerian literature, it is considered the world's earliest literature.

Harper's Songs are ancient Egyptian texts that originated in tomb inscriptions of the Middle Kingdom, which in the main praise life after death and were often used in funerary contexts. These songs display varying degrees of hope in an afterlife that range from the skeptical through to the more traditional expressions of confidence. These texts are accompanied by drawings of blind harpists and are therefore thought to have been sung. Thematically they have been compared with The Immortality of Writers in their expression of rational skepticism.

The Instructions of Kagemni is an ancient Egyptian instructional text of wisdom literature which belongs to the sebayt ('teaching') genre. Although the earliest evidence of its compilation dates to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, its authorship has traditionally yet dubiously been attributed to Kagemni, a vizier who served during the reign of the Pharaoh Sneferu (r. 2613–2589 BC), founder of the Fourth Dynasty.

Insinger Papyrus is a papyrus find from ancient Egypt and contains one of the oldest extant writings about Egyptian wisdom teachings (Sebayt). The manuscript is dated to around the 1st century BC according to the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden where the main part is kept. Other sources suggest it dates to the 1st century AD, and to the 3rd century BC. Fragments have also been found in other collections.

In Ancient Egyptian religion, Medjed is a minor deity mentioned in certain copies of the Book of the Dead. While not much is known about the deity, his ghost-like depiction in the Greenfield papyrus has earned him popularity in modern Japanese culture, and he has appeared as a character in video games and anime.

The Art Institute of Chicago contains a Book of the Dead scroll, an Ancient Egyptian papyrus depicting funerary spells. This scroll of funerary spells serves as a protection from "Second Death". In ancient Egyptian spiritual practice, the term "Second Death" refers to the phenomenon of the body permanently separating from the soul. The Book of the Dead scroll is made of papyrus, a material made of reed plants cultivated on marshy plantations, which is then cut into strips and left to dry in horizontal and vertical rows. The scroll also contains pigments used to inscribe the funerary spells.

The Breathing Permit of Hôr or Hor Book of Breathing is a Ptolemaic-era funerary text written for a Theban priest named Hôr. The breathing permit or Book of Breathing assisted its owner in navigating through the afterlife, being judged worthy and living forever.