A tort, in common law jurisdiction, is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits a tortious act. It can include the intentional infliction of emotional distress, negligence, financial losses, injuries, invasion of privacy and many other things.

The abortion debate is the ongoing controversy surrounding the moral, legal, and religious status of induced abortion. The sides involved in the debate are the self-described "pro-choice" and "pro-life" movements. "Pro-choice" emphasizes the right of women to decide whether to terminate a pregnancy. "Pro-life" emphasizes the right of the embryo or fetus to gestate to term and be born. Both terms are considered loaded in mainstream media, where terms such as "abortion rights" or "anti-abortion" are generally preferred. Each movement has, with varying results, sought to influence public opinion and to attain legal support for its position.

Abortion in Canada is legal at all stages of pregnancy and funded in part by the Canada Health Act. While some non-legal barriers to access continue to exist, such as lacking equal access to providers, Canada is the only nation with absolutely no specific legal restrictions on abortion. Medical regulations and accessibility vary between provinces.

The Unborn Victims of Violence Act of 2004 is a United States law which recognizes an embryo or fetus in utero as a legal victim, if they are injured or killed during the commission of any of over 60 listed federal crimes of violence. The law defines "child in utero" as "a member of the species Homo sapiens, at any stage of development, who is carried in the womb."

English tort law concerns the compensation for harm to people's rights to health and safety, a clean environment, property, their economic interests, or their reputations. A "tort" is a wrong in civil, rather than criminal law, that usually requires a payment of money to make up for damage that is caused. Alongside contracts and unjust enrichment, tort law is usually seen as forming one of the three main pillars of the law of obligations.

Tremblay v Daigle [1989] 2 S.C.R. 530, was a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in which it was found that a fetus has no legal status in Canada as a person, either in Canadian common law or in Quebec civil law. This, in turn, meant that men, while claiming to be protecting fetal rights, cannot acquire injunctions to stop their partners from obtaining abortions in Canada.

Kamloops v Nielsen, [1984] 2 SCR 2 ("Kamloops") is a leading Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decision setting forth the criteria which must be met in order for a plaintiff to make a claim in tort for pure economic loss. In this regard, the Kamloops case is significant because the SCC adopted the "proximity" test set out in the House of Lords decision, Anns v Merton LBC. Kamloops is also significant as it articulates the "discoverability principle" in which the commencement of a limitation period is delayed until the plaintiff becomes aware of the material facts on which a cause of action are discovered or ought to have been discovered by the plaintiff in the exercise of reasonable diligence. This was later adopted and refined in Central Trust Co v Rafuse. Finally, Kamloops develops the law governing circumstances where a plaintiff can sue the government in tort.

Fetal rights are the moral rights or legal rights of the human fetus under natural and civil law. The term fetal rights came into wide usage after the landmark case Roe v. Wade that legalized abortion in the United States in 1973. The concept of fetal rights has evolved to include the issues of maternal drug and alcohol abuse. The only international treaty specifically tackling fetal rights is the American Convention on Human Rights which envisages the right to life of the fetus. While international human rights instruments lack a universal inclusion of the fetus as a person for the purposes of human rights, the fetus is granted various rights in the constitutions and civil codes of several countries. Many legal experts believe there is an increasing need to settle the legal status of the fetus.

R v Sullivan, [1991] 1 S.C.R. 489 was a decision by the Supreme Court of Canada on negligence and whether a partially born fetus is a person.

The "born alive" rule is a common law legal principle that holds that various criminal laws, such as homicide and assault, apply only to a child that is "born alive". U.S. courts have overturned this rule, citing recent advances in science and medicine; and in several states, feticide statutes have been explicitly framed or amended to include fetuses in utero. Abortion in Canada is still governed by the born alive rule, as courts continue to hold to its foundational principles. In 1996, the Law Lords confirmed that the rule applied in English law but that alternative charges existed in lieu, such as a charge of unlawful or negligent manslaughter instead of murder.

In re A.C. was a 1987 District of Columbia Court of Appeals case. It was the first appellate court case decided against forced Caesarean sections, although the decision was issued after the fatal procedure was performed. Physicians performed a Caesarean section upon patient Angela Carder without informed consent in an unsuccessful attempt to save the life of her fetus. The case stands as a landmark in United States case law establishing the rights of informed consent and bodily integrity for pregnant women.

F v R, is a tort law case. It is a seminal case on what information medical professionals have a duty to inform patients of at common law.

Pemberton v. Tallahassee Memorial Regional Center, 66 F. Supp. 2d 1247, is a case in the United States regarding reproductive rights. In particular, the case explored the limits of a woman's right to choose her medical treatment in light of fetal rights at the end of pregnancy.

Wrongful birth is a legal cause of action in some common law countries in which the parents of a congenitally diseased child claim that their doctor failed to properly warn of their risk of conceiving or giving birth to a child with serious genetic or congenital abnormalities. Thus, the plaintiffs claim, the defendant prevented them from making a truly informed decision as to whether or not to have the child. Wrongful birth is a type of medical malpractice tort. It is distinguished from wrongful life, in which the child sues the doctor.

Foeticide is the act of destroying a fetus or causing an abortion.

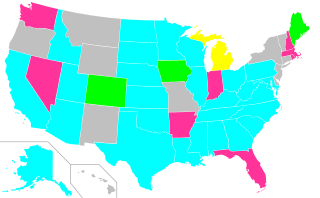

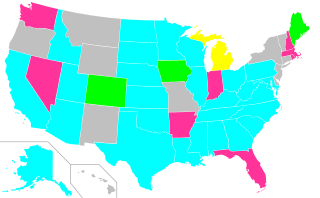

"Born alive" laws in the United States are fetal rights laws which extend various criminal laws, such as homicide and assault, to cover unlawful death or other harm done to a fetus in utero or to an infant that is no longer being carried in pregnancy and exists outside of its mother. The basis for such laws stems from advances in medical science and social perception which allow a fetus to be seen and medically treated as an individual in the womb and perceived socially as a person, for some or all of the pregnancy.

Obstetric medicine, similar to maternal medicine, is a sub-specialty of general internal medicine and obstetrics that specializes in process of prevention, diagnosing, and treating medical disorders in with pregnant women. It is closely related to the specialty of maternal-fetal medicine, although obstetric medicine does not directly care for the fetus. The practice of obstetric medicine, or previously known as "obstetric intervention," primarily consisted of the extraction of the baby during instances of duress, such as obstructed labor or if the baby was positioned in breech.

Maternal somatic support after brain death occurs when a brain dead patient is pregnant and her body is kept alive to deliver a fetus. It occurs very rarely internationally. Even among brain dead patients, in a U.S. study of 252 brain dead patients from 1990–96, only 5 (2.8%) cases involved pregnant women between 15 and 45 years of age.

Abortion in Afghanistan is affected by the religious constraints from the national religion, Islam, and by the extremely high birthrates. Afghanistan has one of the highest fertility rates, but its levels are decreasing since the fall of the Taliban, as aid workers can now enter the country to help with fertility and decrease mortality rates. Afghan law is influenced by Islamic law, which comes from the Qur’an. These laws state that abortion is only legal if it is performed to save the life of the mother or if the child is going to be born with a severe disability. This interpretation of Islamic law is based in Islamic medicine, as Muslims cherish the sanctity of human life and believe God does not cause harm or illnesses that are incurable. Due to these constraints, women choose either to pursue an abortion illegally or be shunned by society due to a pregnancy outside of the socially accepted norms. Contraception is approved by Islam when it prevents the formation of the zygote and prevents implantation in the uterus.

Maternal-fetal conflict, also known as obstetric conflict, occurs when a pregnant woman's (maternal) interests conflict with the interests of her baby (fetus). Legal and ethical considerations involving women's rights and the rights of the fetus as a patient and future child, have become more complicated with advances in medicine and technology. Maternal-fetal conflict can occur in situations where the mother denies health recommendations that can benefit the fetus or make life choices that can harm the fetus. There are maternal-fetal conflict situations where the law becomes involved, but most physicians avoid involving the law for various reasons.