Biography

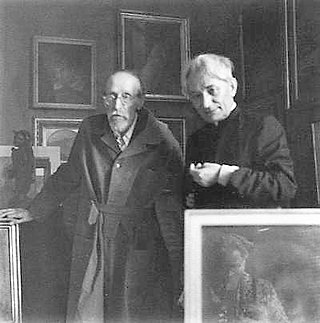

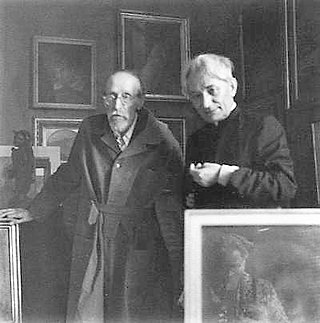

Domenico Giuliotti was born in San Casciano in Val di Pesa, on 18 February 1877, on a farm only a few miles from the city of Florence. When he was barely old enough to go to school his parents sent him to live with an uncle, in a little hamlet near his birthplace. This uncle, Virgilio, was a notary public who had become the vice pretore of the district. As a magistrate he took pride in his judicial duties, and he and his wife, having no children of their own, hoped that some day their young nephew would follow in the footsteps of his jurist uncle. Consequently, Giuliotti, much against his inclinations, eventually went to Siena to study law. Before taking a degree he moved to Rome, under the pretext, as he explained to his family, that a degree conferred by the University of Rome, whose professors were renowned, carried with it more prestige than a degree from that of Siena.

During his university years Giuliotti began to exhibit strong anarchist and radical leanings. As the years went by, however, his outlook changed. He was terrified at the sight of the havoc wrought by the godless principles of a godless society with its worship of wealth and of everything that wealth can buy. The situation seemed hopeless, and Giuliotti was depressed almost to the point of despair, for it seemed to him that these diabolical principles were "preparing a generation capable of making hell turn pale." [3] In his endeavor to find something to counteract these evils, Giuliotti wandered from one ideology to the other. [4]

Finally, thanks to his reading the works of nineteenth century French Catholic traditionalist thinkers – De Maistre, De Bonald, Hello, Veuillot, Bloy – he went back to the faith of his childhood, "to the Eternal Church that commands and teaches from Rome," as his friend Giovanni Papini would later put it. [4]

In 1913 Giuliotti founded the journal La Torre with his friend Federigo Tozzi and used it to express deeply reactionary Catholic views. The periodical was founded by Giuliotti and Tozzi with the express purpose of combatting socialism, anarchism, and everything opposed to the principles of the "Throne and the Altar." Giuliotti was also one of the major collaborators of Il Frontespizio , an important cultural magazine which gathered together noteworthy Italian writers like Piero Bargellini, Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici. [7]

Besides the well-known Dizionario dell'omo salvatico, written in collaboration with Papini, Giuliotti has published a score of books of poetry, tales and novels. Most of these are of a fragmentary nature, consisting of essays, sketches, book reviews, and journalistic articles such as an editor or a columnist might write. As one would expect, the spirit and the tone of these writings vary with the purpose and the content of the work. So much so, that as the French critic Marcel Brion says of Giuliotti, "in him one finds the sweetness of Jacopone da Todi, the severe and serious naturalism of Giotto's frescoes, the winged flight of Dante's terzine, and, often enough, a violence of reproach and satire that reminds one of Savonarola."

Mauro Cristofani was a linguist and researcher in Etruscan studies.

Giovanni Papini was an Italian journalist, essayist, novelist, short story writer, poet, literary critic, and philosopher. A controversial literary figure of the early and mid-twentieth century, he was the earliest and most enthusiastic representative and promoter of Italian pragmatism. Papini was admired for his writing style and engaged in heated polemics. Involved with avant-garde movements such as futurism and post-decadentism, he moved from one political and philosophical position to another, always dissatisfied and uneasy: he converted from anti-clericalism and atheism to Catholicism, and went from convinced interventionism – before 1915 – to an aversion to war. In the 1930s, after moving from individualism to conservatism, he finally became a fascist, while maintaining an aversion to Nazism.

Giuseppe Prezzolini was an Italian literary critic, journalist, editor and writer. He later became an American citizen.

Piero Calamandrei was an Italian author, jurist, soldier, university professor, and politician. He was one of Italy's leading authorities on the law of civil procedure.

Paolo Segneri was an Italian Jesuit preacher, missionary, and ascetical writer.

Alessandro Verri was an Italian author.

Romano Romanelli was an Italian artist, writer, and naval officer, known for his sculptures and his medals.

Benedetto Pamphili was an Italian cardinal, patron of the arts and librettist for many composers.

Pietro Trifone, is an Italian linguist.

Marcello Landi (1916–1993) was an Italian painter and poet.

Vincenzo Borghini was an Italian monk, artist, philologist, and art collector of Florence, Italy.

Orazio Bacci was an Italian Liberal Party politician. He was the 12th mayor of Florence, Kingdom of Italy. He died in Rome.

Nicoletta Maraschio is an academic teacher of "History of Italian Language" at University of Florence. She was the first woman in charge of Accademia della Crusca, from 2008 to 2014, succeeding Francesco Sabatini.

Giovanni Bertacchi was an Italian poet, teacher and literary critic.

Giovanni Battista Ciotti, or Ciotto, was an Italian publisher and typographer.

Omero Vecchi, known by his pen name Luciano Folgore, was an Italian poet.

Corrado Govoni. was an Italian poet. His work dealt with modern urban representations, the states of memory, nostalgia, and longing, using an expressive and evocative style of writing.

Antonio Baldini was an Italian journalist, literary critic and writer.

Beniamino De Ritis was an Italian-American journalist-commentator and author.

Cesare Angelini was an Italian presbyter, writer and literary critic.

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.