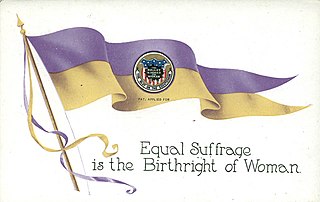

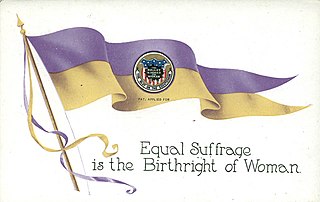

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby went into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

Sidney Clopton Lanier was an American musician, poet and author. He served in the Confederate States Army as a private, worked on a blockade-running ship for which he was imprisoned, taught, worked at a hotel where he gave musical performances, was a church organist, and worked as a lawyer. As a poet he sometimes used dialects. Many of his poems are written in heightened, but often archaic, American English. He became a flautist and sold poems to publications. He eventually became a professor of literature at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and is known for his adaptation of musical meter to poetry. Many schools, other structures and two lakes are named for him, and he became hailed in the South as the "poet of the Confederacy". A 1972 US postage stamp honored him as an "American poet".

Rebecca Ann Felton was an American writer, politician, white supremacist, and slave owner who was the first woman to serve in the United States Senate, serving for only one day. She was a prominent member of the Georgia upper class who advocated for prison reform, women's suffrage and education reform. Her husband, William Harrell Felton, served in both the United States House of Representatives and the Georgia House of Representatives, and she helped organize his political campaigns. Historian Numan Bartley wrote that by 1915 Felton "was championing a lengthy feminist program that ranged from prohibition to equal pay for equal work yet never accomplished any feat because she held her role because of her husband."

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NWP advocated for other issues including the Equal Rights Amendment. The most prominent leader of the National Woman's Party was Alice Paul, and its most notable event was the 1917–1919 Silent Sentinels vigil outside the gates of the White House.

The Silent Sentinels, also known as the Sentinels of Liberty, were a group of over 2,000 women in favor of women's suffrage organized by Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, who nonviolently protested in front of the White House during Woodrow Wilson's presidency starting on January 10, 1917. Nearly 500 were arrested, and 168 served jail time. They were the first group to picket the White House. Later, they also protested in Lafayette Square, not stopping until June 4, 1919 when the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed both by the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Women's suffrage, or the right of women to vote, was established in the United States over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, first in various states and localities, then nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Laura Clay, co-founder and first president of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association, was a leader of the American women's suffrage movement. She was one of the most important suffragists in the South, favoring the states' rights approach to suffrage. A powerful orator, she was active in the Democratic Party and had important leadership roles in local, state and national politics. In 1920 at the Democratic National Convention, she was one of two women, alongside Cora Wilson Stewart, to be the first women to have their names placed into nomination for the presidency at the convention of a major political party.

Mildred Lewis Rutherford was a prominent white supremacist speaker and author from Athens, Georgia. She served the Lucy Cobb Institute, as its head and in other capacities, for over forty years, and oversaw the addition of the Seney-Stovall Chapel to the school. Heavily involved in many organizations, she became the historian general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), and a speech given for the UDC was the first by a woman to be recorded in the Congressional Record. She was a prolific writer in historical subjects and an advocate of the Lost Cause narrative. Rutherford was distinctive in dressing as a southern belle for her speeches. She held strong pro-Confederacy, proslavery views and opposed women's suffrage.

The Woman Suffrage Procession on March 3, 1913, was the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C. It was also the first large, organized march on Washington for political purposes. The procession was organized by the suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Planning for the event began in Washington in December 1912. As stated in its official program, the parade's purpose was to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded."

Sue Shelton White, called Miss Sue, was a feminist leader originally from Henderson, Tennessee, who served as a national leader of the women's suffrage movement, member of the Silent Sentinels and editor of The Suffragist.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

The Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) was an organization founded in 1903 to support white women's suffrage in Texas. It was originally formed under the name of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA) and later renamed in 1916. TESA did allow men to join. TESA did not allow black women as members, because at the time to do so would have been "political suicide." The El Paso Colored Woman's Club applied for TESA membership in 1918, but the issue was deflected and ended up going nowhere. TESA focused most of their efforts on securing the passage of the federal amendment for women's right to vote. The organization also became the state chapter of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). After women earned the right to vote, TESA reformed as the Texas League of Women Voters.

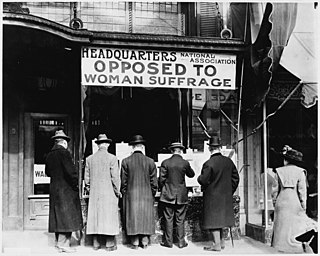

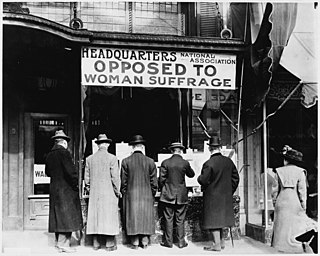

The National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage (NAOWS) was founded in the United States by women opposed to the suffrage movement in 1911. It was the most popular anti-suffrage organization in northeastern cities. NAOWS had influential local chapters in many states, including Texas and Virginia.

The women's suffrage movement began in California in the 19th century and was successful with the passage of Proposition 4 on October 10, 1911. Many of the women and men involved in this movement remained politically active in the national suffrage movement with organizations such as the National American Women's Suffrage Association and the National Woman's Party.

Women's suffrage efforts in Texas began in 1868 at the first Texas Constitutional Convention. In both Constitutional Conventions and subsequent legislative sessions, efforts to provide women the right to vote were introduced, only to be defeated. Early Texas suffragists such as Martha Goodwin Tunstall and Mariana Thompson Folsom worked with national suffrage groups in the 1870s and 1880s. It wasn't until 1893 and the creation of the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) by Rebecca Henry Hayes of Galveston that Texas had a statewide women's suffrage organization. Members of TERA lobbied politicians and political party conventions on women's suffrage. Due to an eventual lack of interest and funding, TERA was inactive by 1898. In 1903, women's suffrage organizing was revived by Annette Finnigan and her sisters. These women created the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in Houston in 1903. TESA sponsored women's suffrage speakers and testified on women's suffrage in front of the Texas Legislature. In 1908 and 1912, speaking tours by Anna Howard Shaw helped further renew interest in women's suffrage in Texas. TESA grew in size and suffragists organized more public events, including Suffrage Day at the Texas State Fair. By 1915, more and more women in Texas were supporting women's suffrage. The Texas Federation of Women's Clubs officially supported women's suffrage in 1915. Also that year, anti-suffrage opponents started to speak out against women's suffrage and in 1916, organized the Texas Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (TAOWS). TESA, under the political leadership of Minnie Fisher Cunningham and with the support of Governor William P. Hobby, suffragists began to make further gains in achieving their goals. In 1918, women achieved the right to vote in Texas primary elections. During the registration drive, 386,000 Texas women signed up during a 17-day period. An attempt to modify the Texas Constitution by voter referendum failed in May 1919, but in June 1919, the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment. Texas became the ninth state and the first Southern state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on June 28, 1919. This allowed white women to vote, but African American women still had trouble voting, with many turned away, depending on their communities. In 1923, Texas created white primaries, excluding all Black people from voting in the primary elections. The white primaries were overturned in 1944 and in 1964, Texas's poll tax was abolished. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed, promising that all people in Texas had the right to vote, regardless of race or gender.

The first women's suffrage group in Georgia, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA), was formed in 1892 by Helen Augusta Howard. Over time, the group, which focused on "taxation without representation" grew and earned the support of both men and women. Howard convinced the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold their first convention outside of Washington, D.C., in 1895. The convention, held in Atlanta, was the first large women's rights gathering in the Southern United States. GWSA continued to hold conventions and raise awareness over the next years. Suffragists in Georgia agitated for suffrage amendments, for political parties to support white women's suffrage and for municipal suffrage. In the 1910s, more organizations were formed in Georgia and the number of suffragists grew. In addition, the Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage also formed an organized anti-suffrage campaign. Suffragists participated in parades, supported bills in the legislature and helped in the war effort during World War I. In 1917 and 1919, women earned the right to vote in primary elections in Waycross, Georgia and in Atlanta respectively. In 1919, after the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land, women still had to wait to vote because of rules regarding voter registration. White Georgia women would vote statewide in 1922. Native American women and African-American women had to wait longer to vote. Black women were actively excluded from the women's suffrage movement in the state and had their own organizations. Despite their work to vote, Black women faced discrimination at the polls in many different forms. Georgia finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

Women's suffrage had early champions among men in Arkansas. Miles Ledford Langley of Arkadelphia, Arkansas proposed a women's suffrage clause during the 1868 Arkansas Constitutional Convention. Educator, James Mitchell wanted to see a world where his daughters had equal rights. The first woman's suffrage group in Arkansas was organized by Lizzie Dorman Fyler in 1881. A second women's suffrage organization was formed by Clara McDiarmid in 1888. McDiarmid was very influential on women's suffrage work in the last few decades of the nineteenth century. When she died in 1899, suffrage work slowed down, but did not all-together end. Both Bernie Babcock and Jean Vernor Jennings continued to work behind the scenes. In the 1910s, women's suffrage work began to increase again. socialist women, like Freda Hogan were very involved in women's suffrage causes. Other social activists, like Minnie Rutherford Fuller became involved in the Political Equality League (PEL) founded in 1911 by Jennings. Another statewide suffrage group, also known as the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was organized in 1914. AWSA decided to work towards helping women vote in the important primary elections in the state. The first woman to address the Arkansas General Assembly was suffragist Florence Brown Cotnam who spoke in favor of a women's suffrage amendment on February 5, 1915. While that amendment was not completely successful, Cotnam was able to persuade the Arkansas governor to hold a special legislative session in 1917. That year Arkansas women won the right to vote in primary elections. In May 1918, between 40,000 and 50,000 white women voted in the primaries. African American voters were restricted from voting in primaries in the state. Further efforts to amend the state constitution took place in 1918, but were also unsuccessful. When the Nineteenth Amendment passed the United States Congress, Arkansas held another special legislative session in July 1919. The amendment was ratified on July 28 and Arkansas became the twelfth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Mary Latimer McLendon was an activist in the prohibition and women's suffrage movements in the U.S. state of Georgia.