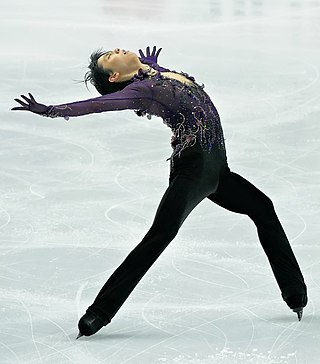

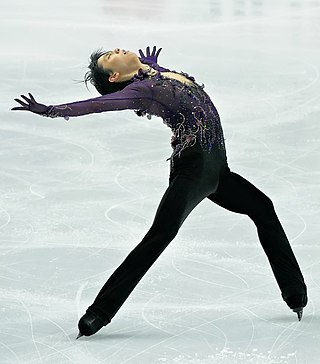

Figure skating is a sport in which individuals, pairs, or groups perform on figure skates on ice. It was the first winter sport to be included in the Olympic Games, when it was contested at the 1908 Olympics in London. The Olympic disciplines are men's singles, women's singles, pair skating, and ice dance; the four individual disciplines are also combined into a team event, which was first included in the Winter Olympics in 2014. The non-Olympic disciplines include synchronized skating, Theater on Ice, and four skating. From intermediate through senior-level competition, skaters generally perform two programs, which, depending on the discipline, may include spins, jumps, moves in the field, lifts, throw jumps, death spirals, and other elements or moves.

The shot put is a track and field event involving "putting" (throwing) a heavy spherical ball—the shot—as far as possible. For men, the sport has been a part of the modern Olympics since their revival (1896), and women's competition began in 1948.

Figure skating jumps are an element of three competitive figure skating disciplines: men's singles, women's singles, and pair skating – but not ice dancing. Jumping in figure skating is "relatively recent". They were originally individual compulsory figures, and sometimes special figures; many jumps were named after the skaters who invented them or from the figures from which they were developed. It was not until the early part of the 20th century, well after the establishment of organized skating competitions, when jumps with the potential of being completed with multiple revolutions were invented and when jumps were formally categorized. In the 1920s Austrian skaters began to perform the first double jumps in practice. Skaters experimented with jumps, and by the end of the period, the modern repertoire of jumps had been developed. Jumps did not have a major role in free skating programs during international competitions until the 1930s. During the post-war period and into the 1950s and early 1960s, triple jumps became more common for both male and female skaters, and a full repertoire of two-revolution jumps had been fully developed. In the 1980s men were expected to complete four or five difficult triple jumps, and women had to perform the easier triples. By the 1990s, after compulsory figures were removed from competitions, multi-revolution jumps became more important in figure skating.

Ice skates are metal blades attached underfoot and used to propel the bearer across a sheet of ice while ice skating.

Inline skates are a type of roller skate used for inline skating. Unlike typical roller skates, which have two front and two rear wheels, inline skates typically have two to five wheels arranged in a single line. Some, especially those for recreation, have a rubber "stop" or "brake" block attached to the rear of one or occasionally both of the skates so that the skater can slow down or stop by leaning back on the foot with the brake skate.

Inline speed skating is the roller sport of racing on inline skates. The sport may also be called inline racing, or speed skating by participants. Although it primarily evolved from racing on traditional roller skates, the sport is similar enough to ice speed skating that many competitors are known to switch between inline and ice speed skating according to the season.

Chad Hedrick is an American inline speed skater and ice speed skater. He was born in Spring, Texas.

KC Boutiette is an American speed skater from Tacoma, Washington, and a four-time Olympian. He was first of the wave of inline speed skaters who made the transition from inline to ice in order to have a shot at going to the Olympics.

The toe loop jump is the simplest jump in the sport of figure skating. It was invented in the 1920s by American professional figure skater Bruce Mapes. The toe loop is accomplished with a forward approach on the inside edge of the blade; the skater then switches to a backward-facing position before their takeoff, which is accomplished from the skater's right back outside edge and left toepick. The jump is exited from the back outside edge of the same foot. It is often added to more difficult jumps during combinations and is the most common second jump performed in combinations. It is also the most commonly attempted jump.

Artistic roller skating is a competitive sport similar to figure skating but where competitors wear roller skates instead of ice skates. Within artistic roller skating, there are several disciplines:

A spiral is an element in figure skating where the skater glides on one foot while raising the free leg above hip level. It is akin to the arabesque in ballet.

Finning techniques are the skills and methods used by swimmers and underwater divers to propel themselves through the water and to maneuver when wearing swimfins. There are several styles used for propulsion, some of which are more suited to particular swimfin configurations. There are also techniques for positional maneuvering, such as rotation on the spot, which may not involve significant locational change. Use of the most appropriate finning style for the circumstances can increase propulsive efficiency, reduce fatigue, improve precision of maneuvering and control of the diver's position in the water, and thereby increase the task effectiveness of the diver and reduce the impact on the environment. Propulsion through water requires much more work than through air due to higher density and viscosity. Diving equipment which is bulky usually increases drag, and reduction of drag can significantly reduce the effort of finning. This can be done to some extent by streamlining diving equipment, and by swimming along the axis of least drag, which requires correct diver trim. Efficient production of thrust also reduces the effort required, but there are also situations where efficiency must be traded off against practical necessity related to the environment or task in hand, such as the ability to maneuver effectively and resistance to damage of the equipment.

Heel-toe technique is a foot technique that drummers use to be able to play single strokes or double strokes on the bass drum, hi-hat, or other pedals.

An Ina Bauer is a "moves in the field" element in figure skating in which a skater skates on two parallel blades. One foot is on a forward edge and the other leg is on a backwards and different parallel edge. The forward leg is bent slightly and the trailing leg is straight. If the leading leg is on the inside edge, the move is known as an inside ina bauer. If the skater is on the outside edge, it is known as an outside ina bauer. Many skaters bend backwards while performing this move, although this is not required. The most flexible skaters can bend over almost completely backwards. When performed this way, the move is called a layback Ina Bauer, after the layback position.

A hydroblade is a figure skating edge move or connecting step in which a skater glides on a deep edge with the body stretched in a very low position, almost touching the ice. Several variations in position are possible, but one commonly performed by singles skaters is on a back inside edge with the knee of the skating leg deeply bent, the free leg crossed behind and extended outside the circle, and the upper body leaning into the circle with two, one, or no hands skimming the ice.

The following is a glossary of figure skating terms, sorted alphabetically.

Crossovers are a basic stroking technique in figure skating for gaining impetus while skating along a curve or circle. They may be performed while skating either forwards or backwards.

British Ice Skating is the national governing body of ice skating within the United Kingdom. Formed in 1879, it is responsible for overseeing all disciplines of ice skating: figure skating ; synchronised skating; and speed skating.

Competitive cross-country skiing encompasses a variety of race formats and course lengths. Rules of cross-country skiing are sanctioned by the International Ski Federation and by various national organizations. International competitions include the FIS Nordic World Ski Championships, the FIS Cross-Country World Cup, and at the Winter Olympic Games. Such races occur over homologated, groomed courses designed to support classic (in-track) and freestyle events, where the skiers may employ skate skiing. It also encompasses cross-country ski marathon events, sanctioned by the Worldloppet Ski Federation, and cross-country ski orienteering events, sanctioned by the International Orienteering Federation. Related forms of competition are biathlon, where competitors race on cross-country skis and stop to shoot at targets with rifles, and paralympic cross-country skiing that allows athletes with disabilities to compete at cross-country skiing with adaptive equipment.

The skating technique is a style of cross-country skiing in which the leg kick is made using the skate step. This style has been established as a revolutionary development of cross-country skiing since the mid-1980s and allows faster movement compared to the classic style. Since 1985, international competitions have been held separately in the classic and free technique, with the skating technique being used in free technique competitions.