A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or revered objects. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, but not defined, by formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, sacral symbolism, and performance.

Anthropology of religion is the study of religion in relation to other social institutions, and the comparison of religious beliefs and practices across cultures. The anthropology of religion, as a field, overlaps with but is distinct from the field of Religious Studies. The history of anthropology of religion is a history of striving to understand how other people view and navigate the world. This history involves deciding what religion is, what it does, and how it functions. Today, one of the main concerns of anthropologists of religion is defining religion, which is a theoretical undertaking in and of itself. Scholars such as Edward Tylor, Emile Durkheim, E.E. Evans Pritchard, Mary Douglas, Victor Turner, Clifford Geertz, and Talal Asad have all grappled with defining and characterizing religion anthropologically.

A persona is a strategic mask of identity in public, the public image of one's personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional. character. It is also considered "an intermediary between the individual and the institution."

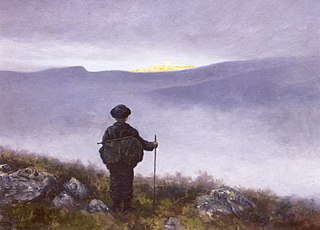

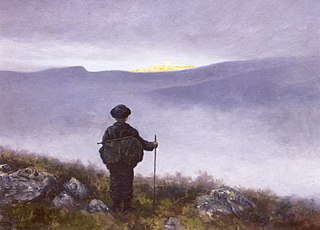

A quest is a journey toward a specific mission or a goal. It serves as a plot device in mythology and fiction: a difficult journey towards a goal, often symbolic or allegorical. Tales of quests figure prominently in the folklore of every nation and ethnic culture. In literature, the object of a quest requires great exertion on the part of the hero, who must overcome many obstacles, typically including much travel. The aspect of travel allows the storyteller to showcase exotic locations and cultures. The object of a quest may also have supernatural properties, often leading the protagonist into other worlds and dimensions. The moral of a quest tale often centers on the changed character of the hero.

A villain is a stock character, whether based on a historical narrative or one of literary fiction. Random House Unabridged Dictionary defines such a character as "a cruelly malicious person who is involved in or devoted to wickedness or crime; scoundrel; or a character in a play, novel, or the like, who constitutes an important evil agency in the plot". The antonym of a villain is a hero.

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals. Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally related groups or sets of roles, with different functions, meanings, or purposes. Examples of social structure include family, religion, law, economy, and class. It contrasts with "social system", which refers to the parent structure in which these various structures are embedded. Thus, social structures significantly influence larger systems, such as economic systems, legal systems, political systems, cultural systems, etc. Social structure can also be said to be the framework upon which a society is established. It determines the norms and patterns of relations between the various institutions of the society.

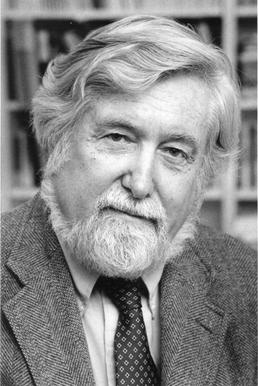

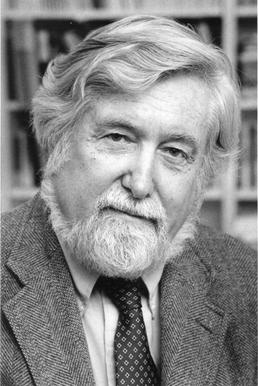

Clifford James Geertz was an American anthropologist who is remembered mostly for his strong support for and influence on the practice of symbolic anthropology and who was considered "for three decades... the single most influential cultural anthropologist in the United States." He served until his death as professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton.

Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp was a Soviet folklorist and scholar who analysed the basic structural elements of Russian folk tales to identify their simplest irreducible structural units.

In narrative theory, an actant in the actantial model of semiotic narrative analysis describes the roles different characters have in advancing a narrative. Bruno Latour writes,

An “actor” in [actor-network theory] is a semiotic definition -an actant-, that is, something that acts or to which activity is granted by others. It implies no special motivation of human individual actors, nor of humans in general. An actant can literally be anything provided it is granted to be the source of an action.

Symbolic anthropology or, more broadly, symbolic and interpretive anthropology, is the study of cultural symbols and how those symbols can be used to gain a better understanding of a particular society. According to Clifford Geertz, "[b]elieving, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning". In theory, symbolic anthropology assumes that culture lies within the basis of the individuals’ interpretation of their surrounding environment, and that it does not in fact exist beyond the individuals themselves. Furthermore, the meaning assigned to people's behavior is molded by their culturally established symbols. Symbolic anthropology aims to thoroughly understand the way meanings are assigned by individuals to certain things, leading then to a cultural expression. There are two majorly recognized approaches to the interpretation of symbolic anthropology, the interpretive approach, and the symbolic approach. Both approaches are products of different figures, Clifford Geertz (interpretive) and Victor Turner (symbolic). There is also another key figure in symbolic anthropology, David M. Schneider, who does not particularly fall into either of the schools of thought. Symbolic anthropology follows a literary basis instead of an empirical one meaning there is less of a concern with objects of science such as mathematics or logic, instead of focusing on tools like psychology and literature. That is not to say fieldwork is not done in symbolic anthropology, but the research interpretation is assessed in a more ideological basis.

Kejawèn or Javanism, also called Kebatinan, Agama Jawa, and Kepercayaan, is a Javanese cultural tradition, consisting of an amalgam of Animistic, Buddhist, Islamic and Hindu aspects. It is rooted in Javanese history and religiosity, syncretizing aspects of different religions and traditions.

The false hero is a stock character in fairy tales, and sometimes also in ballads. The character appears near the end of a story in order to claim to be the hero or heroine and is usually of the same sex as the hero or heroine. The false hero presents some claim to the position. By testing, it is revealed that the claims are false, and the hero's true. The false hero is usually punished, and the true hero put in his place.

Semar is a character in Javanese mythology who frequently appears in wayang shadow plays. He is one of the punokawan (clowns) but is divine and very wise. He is the dhanyang of Java, and is regarded by some as the most sacred figure of the wayang set. He is said to be the god Sang Hyang Ismaya in human form.

Sociological, psychological, and anthropological theories about religion generally attempt to explain the origin and function of religion. These theories define what they present as universal characteristics of religious belief and practice.

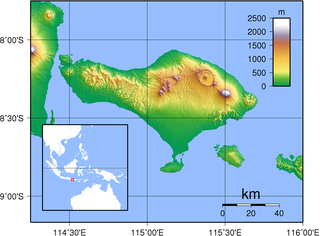

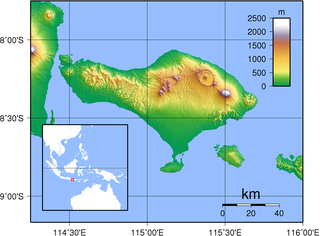

"Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight" is an essay by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz included in the book The Interpretation of Cultures (1973). Considered Geertz's most seminal work, it addresses the symbolism and social dynamics of cockfighting (sabungan) in Balinese culture. It is an important example of Geertz's use of "thick description" as an anthropological approach.

An actor or actress is a person who portrays a character in a production. The actor performs "in the flesh" in the traditional medium of the theatre or in modern media such as film, radio, and television. The analogous Greek term is ὑποκριτής (hupokritḗs), literally "one who answers". The actor's interpretation of a role—the art of acting—pertains to the role played, whether based on a real person or fictional character. This can also be considered an "actor's role," which was called this due to scrolls being used in the theaters. Interpretation occurs even when the actor is "playing themselves", as in some forms of experimental performance art.

Punggawa is a title for a traditional local administrator, used in various parts of Indonesia. On Bali and by extension Lombok, the punggawa held the function of a hereditary vassal lord of a district, subservient to the raja. The term originally applied to the northern kingdom Buleleng, the southern district chiefs being known as manca or manca agung. With the Dutch conquest of Bali in 1906-1908, the term was applied by colonial administration to the entire island. On Sulawesi, too, the term was used for chiefs serving a major lord, in the form pongawa. In Javanese culture the punggawa is a court official in shadow plays (wayang).

A Russian fairy tale or folktale is a fairy tale from Russia.

A play is a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between characters and is intended for theatrical performance rather than mere reading. The creator of a play is known as a playwright.

Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali is a 1980 book written by anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Geertz argues that the pre-colonial Balinese state was not a "hydraulic bureaucracy" nor an oriental despotism, but rather, an organized spectacle. The noble rulers of the island were less interested in administering the lives of the Balinese than in dramatizing their rank and hence political superiority through large public rituals and ceremonies. These cultural processes did not support the state, he argues, but were the state.

It is perhaps most clear in what was, after all, the master image of political life: kingship. The whole of the negara - court life, the traditions that organized it, the extractions that supported it, the privileges that accompanied it - was essentially directed toward defining what power was; and what power was what kings were. Particular kings came and went, 'poor passing facts' anonymized in titles, immobilized in ritual, and annihilated in bonfires. But what they represented, the model-and-copy conception of order, remained unaltered, at least over the period we know much about. The driving aim of higher politics was to construct a state by constructing a king. The more consummate the king, the more exemplary the centre. The more exemplary the centre, the more actual the realm.