A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

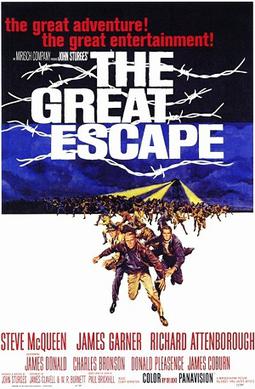

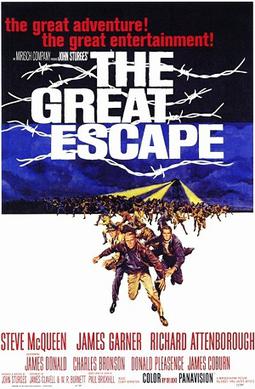

The Great Escape is a 1963 American epic war suspense adventure film starring Steve McQueen, James Garner and Richard Attenborough and featuring James Donald, Charles Bronson, Donald Pleasence, James Coburn, Hannes Messemer, David McCallum, Gordon Jackson, John Leyton and Angus Lennie. It was filmed in Panavision, and its musical score was composed by Elmer Bernstein.

The Third Geneva Convention, relative to the treatment of prisoners of war, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was first adopted in 1929, but significantly revised at the 1949 conference. It defines humanitarian protections for prisoners of war. There are 196 state parties to the Convention.

The Lieber Code was the military law that governed the wartime conduct of the Union Army by defining and describing command responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity; and the military responsibilities of the Union soldier fighting in the American Civil War against the Confederate States of America.

Stalag Luft III was a Luftwaffe-run prisoner-of-war (POW) camp during the Second World War, which held captured Western Allied air force personnel.

A military staff or general staff is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military unit in their command and control role through planning, analysis, and information gathering, as well as by relaying, coordinating, and supervising the execution of their plans and orders, especially in case of multiple simultaneous and rapidly changing complex operations. They are organised into functional groups such as administration, logistics, operations, intelligence, training, etc. They provide multi-directional flow of information between a commanding officer, subordinate military units and other stakeholders. A centralised general staff results in tighter top-down control but requires larger staff at headquarters (HQ) and reduces accuracy of orientation of field operations, whereas a decentralised general staff results in enhanced situational focus, personal initiative, speed of localised action, OODA loop, and improved accuracy of orientation.

Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) is a training program, best known by its military acronym, that prepares U.S. military personnel, U.S. Department of Defense civilians, and private military contractors to survive and "return with honor" in survival scenarios. The curriculum includes survival skills, evading capture, application of the military code of conduct, and techniques for escape from captivity. Formally established by the U.S. Air Force at the end of World War II and the start of the Cold War, it was extended to the Navy and United States Marine Corps and consolidated within the Air Force during the Korean War (1950–1953) with greater focus on "resistance training".

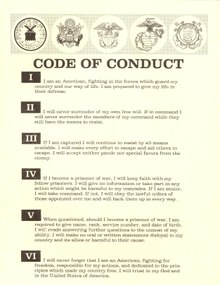

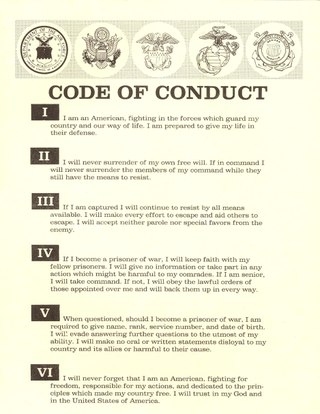

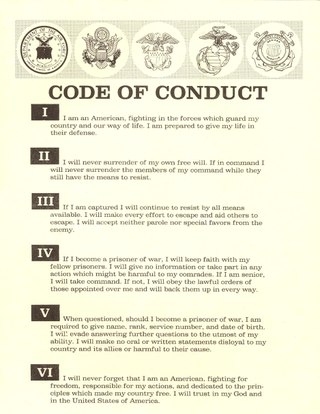

The Code of the U.S. Fighting Force is a code of conduct that is an ethics guide and a United States Department of Defense directive consisting of six articles to members of the United States Armed Forces, addressing how they should act in combat when they must evade capture, resist while a prisoner or escape from the enemy. It is considered an important part of U.S. military doctrine and tradition, but is not formal military law in the manner of the Uniform Code of Military Justice or public international law, such as the Geneva Conventions.

Order No. 270, entitled "On the responsibility of military personnel for surrendering and leaving weapons to the enemy" issued on 16 August 1941, by Joseph Stalin during the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, ordered Red Army personnel to "fight to the last", virtually banned commanders from surrendering, and set out severe penalties for senior officers and deserters regarded as derelicting their duties. Order 270 is widely regarded as the basis of subsequent, often controversial Soviet policies regarding prisoners of war.

Captain Humbert Roque "Rocky" Versace was a United States Army officer of Puerto Rican–Italian descent who was posthumously awarded the United States' highest military decoration—the Medal of Honor—for his heroic actions while a prisoner of war (POW) during the Vietnam War. He was the first member of the U.S. Army to be awarded the Medal of Honor for actions performed in Southeast Asia while in captivity.

The Dix–Hill Cartel was the first official system for exchanging prisoners during the American Civil War. It was signed by Union Major General John A. Dix and Confederate Major General D. H. Hill at Haxall's Landing on the James River in Virginia on July 22, 1862.

John Arthur Dramesi was a United States Air Force (USAF) colonel who was held as a prisoner of war from 2 April 1967 to 4 March 1973 in both Hoa Lo Prison, known as "The Hanoi Hilton", and Cu Loc Prison, "The Zoo", during the Vietnam War.

Josef Bryks, MBE, was a Czechoslovak cavalryman, fighter pilot, prisoner of war and political prisoner.

During World War II, it was estimated that between 35,000 and 50,000 members of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces surrendered to Allied servicemembers prior to the end of World War II in Asia in August 1945. Also, Soviet troops seized and imprisoned more than half a million Japanese troops and civilians in China and other places. The number of Japanese soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who surrendered was limited by the Japanese military indoctrinating its personnel to fight to the death, Allied combat personnel often being unwilling to take prisoners, and many Japanese soldiers believing that those who surrendered would be killed by their captors.

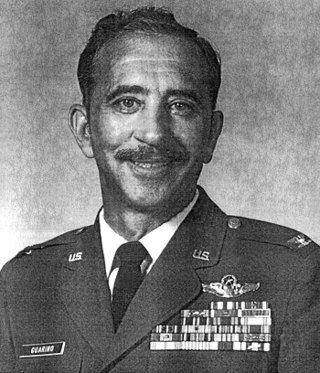

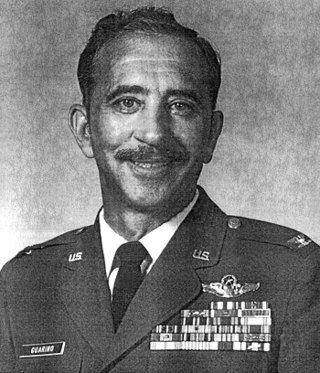

Lawrence Nicholas "Larry" Guarino was a United States Air Force officer, and veteran of three wars. Shot down on his 50th combat mission, he spent more than eight years as a prisoner of war (POW) during the Vietnam War and earned the Air Force Cross.

The Stalag Luft III murders were war crimes perpetrated by members of the Gestapo following the "Great Escape" of Allied prisoners of war from the German Air Force prison camp known as Stalag Luft III on March 25, 1944. Of the 76 successful escapees, 73 were recaptured, most within several days of the breakout, 50 of whom were executed on the personal orders of Adolf Hitler. These executions were conducted within a short period following recapture.

Brigadier General Virgilio Norberto Cordero Jr. was a Puerto Rican soldier who served in the United States Army. Cordero authored two books about his experiences as a prisoner of war, and his participation in the Bataan Death March of World War II.

Members of the United States armed forces were held as prisoners of war (POWs) in significant numbers during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1973. Unlike U.S. service members captured in World War II and the Korean War, who were mostly enlisted troops, the overwhelming majority of Vietnam-era POWs were officers, most of them Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps airmen; a relatively small number of Army enlisted personnel were also captured, as well as one enlisted Navy seaman, Petty Officer Doug Hegdahl, who fell overboard from a naval vessel. Most U.S. prisoners were captured and held in North Vietnam by the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN); a much smaller number were captured in the south and held by the Việt Cộng (VC). A handful of U.S. civilians were also held captive during the war.

The Chalmette Regiment was a regiment of the Louisiana Militia consisting of foreign volunteers called into Confederate service in the American Civil War for 90 days March 1, 1862. Mustered out in May 1862, the regiment was again called into service in May 1863 to defend Fort Beauregard.

Group Captain Douglas Ernest Lancelot "Del" Wilson was a senior officer of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during World War II.