Related Research Articles

Laurence van Cott Niven is an American science fiction writer. His 1970 novel Ringworld won the Hugo, Locus, Ditmar, and Nebula awards. With Jerry Pournelle he wrote The Mote in God's Eye (1974) and Lucifer's Hammer (1977). The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America gave him the 2015 Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award.

The New Wave was a science fiction style of the 1960s and 1970s, characterized by a great degree of experimentation with the form and content of stories, greater imitation of the styles of non-science fiction literature, and an emphasis on the psychological and social sciences as opposed to the physical sciences. New Wave authors often considered themselves as part of the modernist tradition of fiction, and the New Wave was conceived as a deliberate change from the traditions of the science fiction characteristic of pulp magazines, which many of the writers involved considered irrelevant or unambitious.

"Faith of Our Fathers" is a science fiction short story by American writer Philip K. Dick, first published in the anthology Dangerous Visions (1967).

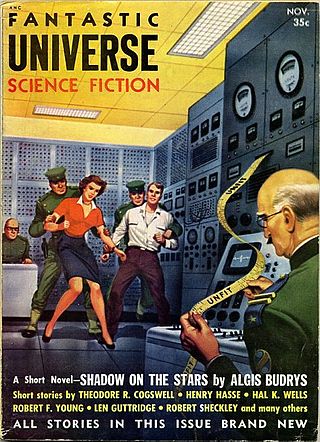

Algirdas Jonas "Algis" Budrys was a Lithuanian-American science fiction author, editor and critic. He was also known under the pen names Frank Mason, Alger Rome in collaboration with Jerome Bixby, John A. Sentry, William Scarff and Paul Janvier. In 1960 he wrote Rogue Moon, a novel. In the 1990s he was the publisher and editor of the science-fiction magazine Tomorrow Speculative Fiction.

Lester del Rey was an American science fiction author and editor. He was the author of many books in the juvenile Winston Science Fiction series, and the fantasy editor at Del Rey Books, the fantasy and science fiction imprint of Ballantine Books, subsequently Random House, working for his fourth wife Judy-Lynn del Rey’s imprint, Del Rey.

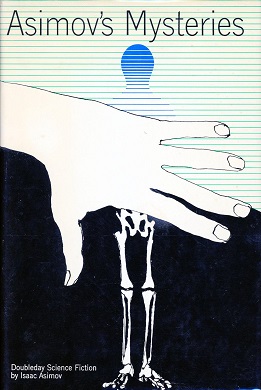

"Marooned off Vesta" is a science fiction short story by American writer Isaac Asimov. It was the third story he wrote, and the first to be published. Written in July 1938 when Asimov was 18, it was rejected by Astounding Science Fiction in August, then accepted in October by Amazing Stories, appearing in the March 1939 issue. Asimov first included it in his 1968 story collection Asimov's Mysteries, and subsequently in the 1973 collection The Best of Isaac Asimov.

"Anniversary" is a science fiction short story by American writer Isaac Asimov. It was first published in the March 1959 issue of Amazing Stories and subsequently appeared in the collections Asimov's Mysteries (1968) and The Best of Isaac Asimov (1973).

The Golden Age of Science Fiction, often identified in the United States as the years 1938–1946, was a period in which a number of foundational works of science fiction literature appeared. In the history of science fiction, the Golden Age follows the "pulp era" of the 1920s and '30s, and precedes New Wave science fiction of the '60s and '70s. The 1950s are, in this scheme, a transitional period. Robert Silverberg, who came of age then, saw the '50s as the true Golden Age.

Asimov's Mysteries, published in 1968, is a collection of 14 short stories by American writer Isaac Asimov, almost all of them science fiction mysteries. The stories were all originally published in magazines between 1954 and 1967, except for "Marooned off Vesta", Asimov's first published story, which first appeared in 1939.

Thomas L. Sherred was an American science fiction writer.

In science fiction, a time viewer, temporal viewer, or chronoscope is a device that allows another point in time to be observed. The concept has appeared since the late 19th century, constituting a significant yet relatively obscure subgenre of time travel fiction and appearing in various media including literature, cinema, and television. Stories usually explain the technology by referencing cutting-edge science, though sometimes invoking the supernatural instead. Most commonly only the past can be observed, though occasionally time viewers capable of showing the future appear; these devices are sometimes limited in terms of what information about the future can be obtained. Other variations on the concept include being able to listen to the past but not view it.

"If All Men Were Brothers, Would You Let One Marry Your Sister?" is a science fiction short story by American writer Theodore Sturgeon. It first appeared in Harlan Ellison's anthology Dangerous Visions in 1967.

Infinity Science Fiction was an American science fiction magazine, edited by Larry T. Shaw, and published by Royal Publications. The first issue, which appeared in November 1955, included Arthur C. Clarke's "The Star", a story about a planet destroyed by a nova that turns out to have been the Star of Bethlehem; it won the Hugo Award for that year. Shaw obtained stories from some of the leading writers of the day, including Brian Aldiss, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Sheckley, but the material was of variable quality. In 1958 Irwin Stein, the owner of Royal Publications, decided to shut down Infinity; the last issue was dated November 1958.

A fix-up is a novel created from several short fiction stories that may or may not have been initially related or previously published. The stories may be edited for consistency, and sometimes new connecting material, such as a frame story or other interstitial narration, is written for the new work. The term was coined by the science fiction writer A. E. van Vogt, who published several fix-ups of his own, including The Voyage of the Space Beagle, but the practice exists outside of science fiction. The use of the term in science fiction criticism was popularised by the first (1979) edition of The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, edited by Peter Nicholls, which credited van Vogt with the term’s creation. The name “fix-up” comes from the changes that the author needs to make in the original texts, to make them fit together as though they were a novel. Foreshadowing of events from the later stories may be jammed into an early chapter of the fix-up, and character development may be interleaved throughout the book. Contradictions and inconsistencies between episodes are usually worked out.

There have been many attempts at defining science fiction. This is a list of definitions that have been offered by authors, editors, critics and fans over the years since science fiction became a genre. Definitions of related terms such as "science fantasy", "speculative fiction", and "fabulation" are included where they are intended as definitions of aspects of science fiction or because they illuminate related definitions—see e.g. Robert Scholes's definitions of "fabulation" and "structural fabulation" below. Some definitions of sub-types of science fiction are included, too; for example see David Ketterer's definition of "philosophically-oriented science fiction". In addition, some definitions are included that define, for example, a science fiction story, rather than science fiction itself, since these also illuminate an underlying definition of science fiction.

Fantastic Universe was a U.S. science fiction magazine which began publishing in the 1950s. It ran for 69 issues, from June 1953 to March 1960, under two different publishers. It was part of the explosion of science fiction magazine publishing in the 1950s in the United States, and was moderately successful, outlasting almost all of its competitors. The main editors were Leo Margulies (1954–1956) and Hans Stefan Santesson (1956–1960).

Niekas was a science fiction fanzine published from 1962–1998 by Ed Meskys – also spelled Meškys – of New Hampshire. It won the 1967 Hugo Award for Best Fanzine, and was nominated two other times, losing in 1966 to ERB-dom and in 1989 to File 770.

Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels, An English-Language Selection, 1949–1984 is a nonfiction book by David Pringle, published by Xanadu in 1985 with a foreword by Michael Moorcock. Primarily, the book comprises 100 short essays on the selected works, covered in order of publication, without any ranking. It is considered an important critical summary of the science fiction field.

Between 1952 and 1954, John Raymond published four digest-size science fiction and fantasy magazines. Raymond was an American publisher of men's magazines who knew little about science fiction, but the field's rapid growth and a distributor's recommendation prompted him to pursue the genre. Raymond consulted and then hired Lester del Rey to edit the first magazine, Space Science Fiction, which appeared in May 1952. Following a second distributor's suggestion that year, Raymond launched Science Fiction Adventures, which del Rey again edited, but under an alias. In 1953, Raymond gave del Rey two more magazines to edit: Rocket Stories, which targeted a younger audience, and Fantasy Magazine, which published fantasy rather than science fiction.

"Rock Diver" is a 1951 short story by American science fiction writer Harry Harrison. It was his first published story, and it is credited with popularizing the concept of matter penetration. The plot reworks a classic western plot about claim jumpers with a sci-fi twist.

References

- 1 2 von Ruff, Al (1995–2011). "Bibliography: E for Effort". The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- 1 2 Budrys, Algis (1985). Benchmarks: Galaxy Bookshelf. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-8093-1187-9. A review that first appeared in the June 1970 Galaxy Science Fiction of Sherred's novel, Alien Island.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit. p. 1101. ISBN 1-85723-124-4.

- 1 2 Pournelle, Jerry (1985). The Science Fiction Yearbook. Baen Science Fiction Books. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-671-55983-4.

- ↑ Miller, P. Schuyler (December 1964). "Backlash". Analog. The Reference Library: 87.

- ↑ del Rey, Lester (1980). The World of Science Fiction, 1926–1976: The History of a Subculture. Garland Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 9780824014469 . Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ↑ Dozois, Gardner (1986). The Year's Best Science Fiction: Third Annual Collection. Bluejay. p. 12. ISBN 0-312-94486-1 . Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ↑ Stableford, Brian (2004). Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction Literature. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4938-0 . Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ↑ Rogers, Alva (1964). A Requiem for Astounding. Advent Publishers. p. 145. ISBN 9780911682083 . Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ↑ Ashley, Michael (2000). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine. Liverpool University Press. p. 191. ISBN 0-85323-855-3 . Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ↑ Pratt, Fletcher (1953). "A Critique of Science Fiction". In Bretnor, Reginald (ed.). Modern Science Fiction: Its Meaning and its Future . Coward-McCann. pp. 73–90.

- ↑ Stableford, Brian (1995). Opening Minds: Essays on Fantastic Literature. Wildside Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780893704032 . Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- ↑ Gunn, James (1996). Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction. Scarecrow Press. p. 84. ISBN 9780810854208 . Retrieved 2011-09-06.