Related Research Articles

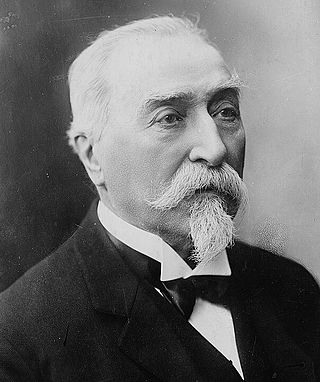

Émile Justin Louis Combes was a French statesman and freemason who led the Lefts Bloc cabinet from June 1902 to January 1905.

Marie-Adélaïde, was Grand Duchess of Luxembourg from 1912 until her abdication in 1919. She was the first Grand Duchess regnant of Luxembourg, its first female monarch since Duchess Maria Theresa and the first Luxembourgish monarch to be born within the territory since Count John the Blind (1296–1346).

The Music of Luxembourg is an important component of the country's cultural life. The new Philharmonie concert hall provides a venue for orchestral concerts while opera is frequently presented in the theatres. Rock, pop and jazz are also popular with a number of successful performers. The wide general interest in music and musical activities in Luxembourg can be seen from the membership of the Union Grand-Duc Adolphe, the national music federation for choral societies, brass bands, music schools, theatrical societies, folklore associations and instrumental groups. Some 340 music groups and associations with over 17,000 individual members are currently represented by the organization.

The Cristero War, also known as the Cristero Rebellion or La Cristiada, was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico from 3 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementation of secularist and anticlerical articles of the 1917 Constitution. The rebellion was instigated as a response to an executive decree by Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles to strictly enforce Article 130 of the Constitution, a decision known as Calles Law. Calles sought to limit the power of the Catholic Church in Mexico, its affiliated organizations and to suppress popular religiosity.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Luxembourg since 1 January 2015. A bill for the legalisation of same-sex marriages was enacted by the Chamber of Deputies on 18 June 2014 and signed into law by Grand Duke Henri on 4 July. Partnerships have also been available in Luxembourg since November 2004.

The linguistic situation in Luxembourg is characterized by the practice and the recognition of three official languages: French, German, and the national language Luxembourgish, established in law in 1984. These three languages are also referred to as the three administrative languages, as the constitution does not specify them as being "official". As of 2018, 98% of the population was able to speak French at more or less a high level, 78% spoke German, and 77% Luxembourgish.

Paul Eyschen was a Luxembourgish politician, statesman, lawyer, and diplomat. He was the eighth prime minister of Luxembourg, serving for twenty-seven years, from 22 September 1888 until his death, on 11 October 1915.

The Party of the Right, abbreviated to PD, was a political party in Luxembourg between 1914 and 1944. It was the direct predecessor of the Christian Social People's Party (CSV), which has ruled Luxembourg for all but fifteen years since.

The Catholic Archdiocese of Luxembourg is an archdiocese of the Latin Church of the Catholic Church in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, comprising the entire Grand Duchy. The diocese was founded in 1870, and it became an archdiocese in 1988. The seat of the archdiocese is the Cathedral of Notre Dame in the city of Luxembourg, and since 2011 the archbishop is Jean-Claude Hollerich.

Irreligion in Mexico refers to atheism, deism, religious skepticism, secularism, and secular humanism in Mexican society, which was a confessional state after independence from Imperial Spain. The first political constitution of the Mexican United States, enacted in 1824, stipulated that Roman Catholicism was the national religion in perpetuity, and prohibited any other religion. Since 1857, however, by law, Mexico has had no official religion; as such, anti-clerical laws meant to promote a secular society, contained in the 1857 Constitution of Mexico and in the 1917 Constitution of Mexico, limited the participation in civil life of Roman Catholic organizations and allowed government intervention in religious participation in politics.

The Falloux Laws promoted Catholic schools in France in the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s. They were voted in during the French Second Republic and promulgated on 15 March 1850 and in 1851, following the presidential election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as president in December 1848 and the May 1849 legislative elections that gave a majority to the conservative Parti de l'Ordre. Named for the Minister of Education Alfred de Falloux, they mainly aimed at promoting Catholic teaching. The Falloux Law of 15 March 1850 also extended the requirements of the Guizot Law of 1833, which had mandated a boys' school in each commune of more than 500 inhabitants, to require a girls' school in those communes. The 1851 law created a mixed system, in which some primary education establishments were public and controlled by the state and others were under the supervision of Catholic congregations.

The education system in France can be traced back to the Roman Empire. Schools may have operated continuously from the later empire to the early Middle Ages in some towns in southern France. The school system was modernized during the French Revolution, but roughly in the 18th and early 19th century debates ranged on the role of religion.

Luxembourgish art can be traced back to Roman times, especially as depicted in statues found across the country and in the huge mosaic from Vichten. Over the centuries, Luxembourg's churches and castles have housed a number of cultural artefacts but these are nearly all ascribed to foreign artists. The first examples of art with a national flavour are paintings and maps of the City of Luxembourg and its fortifications from the end of the 16th until the beginning of the 19th century, although these too were mostly created by foreign artists. Real interest in art among the country's own citizens began in the 19th century with paintings of Luxembourg and the surroundings after the country became a grand duchy in 1815. This was followed by interest in Impressionism and Expressionism in the early 20th century, the richest period in Luxembourg painting, while Abstraction became the focus of art after the Second World War. Today there are a number of successful contemporary artists, some of whom have gained wide international recognition.

The Second School War was a political crisis in Belgium over the issue of religion in education. The conflict lasted between 1950 and 1959 and was ended by a cross-party agreement, known as the School Pact, which clarified the role of religion in the state. It followed a crisis over the same issue in the 19th century, known as the First School War.

The Maulkuerfgesetz was a proposed 1937 law in Luxembourg. Officially, it was entitled the "Law for the Defence of the Political and Social Order" but was nicknamed Maulkuerfgesetz by its opponents. The law would have allowed the Luxembourgish government to ban the Communist Party and dissolve any political organisation which they believed might endanger the constitutional institutions. The members of these parties or organisations would be stripped of their political offices and could not be employed by the state or by local governments.

The Left Bloc was a political alliance in the Chamber of Deputies of Luxembourg at the beginning of the 20th century. The "marriage of convenience" between the Social Democratic Party and the Liberal League was formed in 1908.

The Eyschen Ministry was in office in Luxembourg for 27 years, from 22 September 1888 to 12 October 1915. It was headed by Paul Eyschen, and ended with his death.

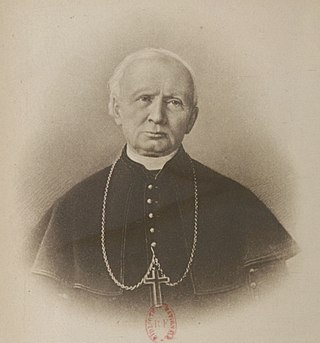

Pierre Nommesch was the Bishop of Luxembourg from 1920 to 1935.

Education in Luxembourg is multilingual and consists of fundamental education, secondary education and higher education.

The first "textbook war" was an education-related conflict that occurred in France between 1882 and 1883, after the secularization of primary education materials by the Ferry law on March 28, 1882.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Moes, Régis. "La réforme scolaire de 1912" Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine . In: forum Nr. 325, January 2013. p. 35-38.

- ↑ Pauly, Michel (1 July 2014). Binsfeld, Andrea; Pauly, Michel; Pettiau, Hérold (eds.). "Kirche und Staat: auch unter Historikern ein Streitthema?". Hémecht. Histoire religieuse - Bilan & Perspectives: Actes des 5es Assises de l’historiographie luxembourgeoise (in German). 66 (3/4): 437–452.