A hook turn or two-stage turn, also known as a Copenhagen Left, is a road cycling manoeuvre or a motor vehicle traffic-control mechanism in which vehicles that would normally turn from the innermost lane of an intersection instead turn from the outermost lane, across all other lanes of traffic.

Bike lanes (US) or cycle lanes (UK) are types of bikeways (cycleways) with lanes on the roadway for cyclists only. In the United Kingdom, an on-road cycle-lane can be firmly restricted to cycles or advisory. In the United States, a designated bicycle lane or class II bikeway (Caltrans) is always marked by a solid white stripe on the pavement and is for 'preferential use' by bicyclists. There is also a class III bicycle route, which has roadside signs suggesting a route for cyclists, and urging sharing the road. A class IV separated bike way (Caltrans) is a bike lane that is physically separate from motor traffic and restricted to bicyclists only.

John Forester was an English-American industrial engineer, specializing in bicycle transportation engineering. A cycling activist, he was known as "the father of vehicular cycling", for creating the Effective Cycling program of bicycle training along with its associated book of the same title, and for coining the phrase "the vehicular cycling principle" – "Cyclists fare best when they act and are treated as drivers of vehicles". His published works also included Bicycle Transportation: A Handbook for Cycling Transportation Engineers.

Vehicular cycling is the practice of riding bicycles on roads in a manner that is in accordance with the principles for driving in traffic. The phrase vehicular cycling was coined by John Forester in the 1970s. In his book Effective Cycling, Forester contends that "Cyclists fare best when they act and are treated as drivers of vehicles".

A wide outside lane (WOL) or wide curb lane (WCL) is an outermost lane of a roadway that is wide enough to be safely shared side by side by a bicycle and a wider motor vehicle at the same time. The terms are used by cyclists and bicycle transportation planners in the United States. Generally, the minimum-width standard for a WOL in the US is 14 feet. A wide outside through lane (WOTL) is a WOL that is intended for use by through traffic.

Bicycle transportation planning and engineering are the disciplines related to transportation engineering and transportation planning concerning bicycles as a mode of transport and the concomitant study, design and implementation of cycling infrastructure. It includes the study and design of dedicated transport facilities for cyclists as well as mixed-mode environments and how both of these examples can be made to work safely. In jurisdictions such as the United States it is often practiced in conjunction with planning for pedestrians as a part of active transportation planning.

Bicycle safety is the use of road traffic safety practices to reduce risk associated with cycling. Risk can be defined as the number of incidents occurring for a given amount of cycling. Some of this subject matter is hotly debated: for example, which types of cycling environment or cycling infrastructure is safest for cyclists. The merits of obeying the traffic laws and using bicycle lighting at night are less controversial. Wearing a bicycle helmet may reduce the chance of head injury in the event of a crash.

A bicycle boulevard, sometimes referred to as a neighborhood greenway, neighborway, neighborhood bikeway or neighborhood byway is a type of bikeway composed of a low-speed street which has been "optimized" for bicycle traffic. Bicycle boulevards discourage cut-through motor-vehicle traffic but may allow local motor-vehicle traffic at low speeds. They are designed to give priority to bicyclists as through-going traffic. They are intended as a low-cost, politically popular way to create a connected network of streets with good bicyclist comfort and/or safety.

A cycle track or cycleway (British) or bikeway, sometimes historically referred to as a sidepath, is a separate route for cycles and not motor vehicles. In some cases cycle tracks are also used by other users such as pedestrians and horse riders. A cycle track can be next to a normal road, and can either be a shared route with pedestrians or be made distinct from both the pavement and general roadway by vertical barriers or elevation differences.

A shared lane marking, shared-lane marking, or sharrow is a street marking installed by various jurisdictions worldwide in an attempt to make cycling safer.

Cycling in New York City is associated with mixed cycling conditions that include dense urban proximities, relatively flat terrain, congested roadways with stop-and-go traffic, and streets with heavy pedestrian activity. The city's large cycling population includes utility cyclists, such as delivery and messenger services; cycling clubs for recreational cyclists; and increasingly commuters. Cycling is increasingly popular in New York City: in 2018 there were approximately 510,000 daily bike trips, compared with 170,000 daily bike trips in 2005.

Toronto, Ontario, like many North American cities, has slowly been expanding its purpose-built cycling infrastructure. The number of cyclists in Toronto has been increasing progressively, particularly in the city's downtown core. As cycling conditions improve, a cycling culture has grown and alternatives such as automobiles are seen as less attractive. The politics of providing resources for cyclists, particularly dedicated bike lanes, has been contentious, particularly since the 2010s.

Cycling in Copenhagen is – as with most cycling in Denmark – an important mode of transportation and a dominating feature of the cityscape, often noticed by visitors. The city offers a variety of favourable cycling conditions — dense urban proximities, short distances and flat terrain — along with an extensive and well-designed system of cycle tracks. This has earned it a reputation as one of the most bicycle-friendly cities in the world. Every day 1.2 million kilometres are cycled in Copenhagen, with 62% of all citizens commuting to work, school, or university by bicycle; in fact, almost as many people commute by bicycle in greater Copenhagen as do those cycle to work in the entire United States. Cycling is generally perceived as a healthier, more environmentally friendly, cheaper, and often quicker way to get around town than by using an automobile.

Cycling in Denmark is both a common and popular recreational and utilitarian activity. Bicycling infrastructure is a dominant feature of both city and countryside infrastructure with segregated dedicated bicycle paths and lanes in many places and the network of 11 Danish National Cycle Routes extends more than 12,000 kilometres (7,500 mi) nationwide. Often bicycling and bicycle culture in Denmark is compared to the Netherlands as a bicycle-nation.

Cycling infrastructure is all infrastructure cyclists are allowed to use. Bikeways include bike paths, bike lanes, cycle tracks, rail trails and, where permitted, sidewalks. Roads used by motorists are also cycling infrastructure, except where cyclists are barred such as many freeways/motorways. It includes amenities such as bike racks for parking, shelters, service centers and specialized traffic signs and signals. The more cycling infrastructure, the more people get about by bicycle.

The history of cycling infrastructure starts from shortly after the bike boom of the 1880s when the first short stretches of dedicated bicycle infrastructure were built, through to the rise of the automobile from the mid-20th century onwards and the concomitant decline of cycling as a means of transport, to cycling's comeback from the 1970s onwards.

A protected intersection or protected junction, also known as a Dutch-style junction, is a type of at-grade road junction in which cyclists and pedestrians are separated from cars. The primary aim of junction protection is to help pedestrians and cyclists be and feel safer at road junctions.

There is debate over the safety implications of cycling infrastructure. Recent studies generally affirm that segregated cycle tracks have a better safety record between intersections than cycling on major roads in traffic. Furthermore, cycling infrastructure tends to lead to more people cycling. A higher modal share of people cycling is correlated with lower incidences of cyclist fatalities, leading to a "safety in numbers" effect though some contributors caution against this hypothesis. On the contrary, older studies tended to come to negative conclusions about mid-block cycle track safety.

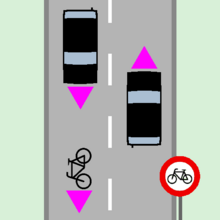

Controversies have surrounded dedicated cycling routes in cities. Some critics of bikeways argue that the focus should instead be placed on educating cyclists in road safety, and others that safety is better served by using the road space for parking. There is debate over whether cycle tracks are an effective factor to encourage cycling or whether other factors are at play.

Cycling infrastructure in the Canadian city of Halifax, Nova Scotia includes most regular streets and roads, bike lanes, protected cycle tracks, local street bikeways, and multi-use pathways.