Related Research Articles

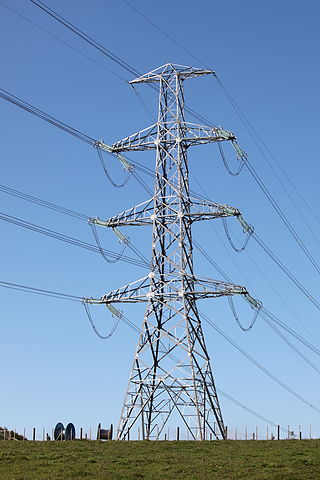

Electricity retailing is the final sale of electricity from generation to the end-use consumer. This is the fourth major step in the electricity delivery process, which also includes generation, transmission and distribution.

The electric power industry covers the generation, transmission, distribution and sale of electric power to the general public and industry. The commercial distribution of electric power started in 1882 when electricity was produced for electric lighting. In the 1880s and 1890s, growing economic and safety concerns lead to the regulation of the industry. What was once an expensive novelty limited to the most densely populated areas, reliable and economical electric power has become an essential aspect for normal operation of all elements of developed economies.

The Exposition Universelle of 1900, better known in English as the 1900 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 14 April to 12 November 1900, to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to accelerate development into the next. It was the sixth of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937. It was held at the esplanade of Les Invalides, the Champ de Mars, the Trocadéro and at the banks of the Seine between them, with an additional section in the Bois de Vincennes, and it was visited by more than fifty million people. Many international congresses and other events were held within the framework of the exposition, including the 1900 Summer Olympics.

The war of the currents was a series of events surrounding the introduction of competing electric power transmission systems in the late 1880s and early 1890s. It grew out of two lighting systems developed in the late 1870s and early 1880s; arc lamp street lighting running on high-voltage alternating current (AC), and large-scale low-voltage direct current (DC) indoor incandescent lighting being marketed by Thomas Edison's company. In 1886, the Edison system was faced with new competition: an alternating current system initially introduced by George Westinghouse's company that used transformers to step down from a high voltage so AC could be used for indoor lighting. Using high voltage allowed an AC system to transmit power over longer distances from more efficient large central generating stations. As the use of AC spread rapidly with other companies deploying their own systems, the Edison Electric Light Company claimed in early 1888 that high voltages used in an alternating current system were hazardous, and that the design was inferior to, and infringed on the patents behind, their direct current system.

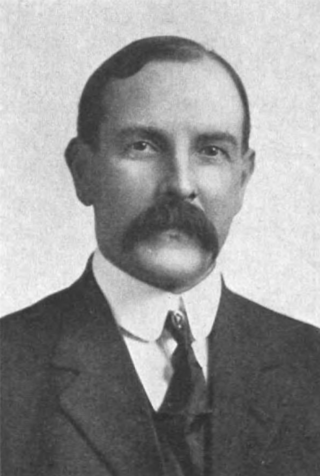

Arthur Edwin Kennelly was an American electrical engineer.

Power engineering, also called power systems engineering, is a subfield of electrical engineering that deals with the generation, transmission, distribution, and utilization of electric power, and the electrical apparatus connected to such systems. Although much of the field is concerned with the problems of three-phase AC power – the standard for large-scale power transmission and distribution across the modern world – a significant fraction of the field is concerned with the conversion between AC and DC power and the development of specialized power systems such as those used in aircraft or for electric railway networks. Power engineering draws the majority of its theoretical base from electrical engineering and mechanical engineering.

Vitascope was an early film projector first demonstrated in 1895 by Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat. They had made modifications to Jenkins' patented Phantoscope, which cast images via film and electric light onto a wall or screen. The Vitascope is a large electrically-powered projector that uses light to cast images. The images being cast are originally taken by a kinetoscope mechanism onto gelatin film. Using an intermittent mechanism, the film negatives produced up to fifty frames per second. The shutter opens and closes to reveal new images. This device can produce up to 3,000 negatives per minute. With the original Phantoscope and before he partnered with Armat, Jenkins displayed the earliest documented projection of a filmed motion picture in June 1894 in Richmond, Indiana.

Pearl Street Station was Thomas Edison's first commercial power plant in the United States. It was located at 255–257 Pearl Street in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City, just south of Fulton Street on a site measuring 50 by 100 feet. The station was built by the Edison Illuminating Company, under the direction of Francis Upton, hired by Thomas Edison.

The Fisk Generating Station, also known as Fisk Street Generating Station or Fisk Station is an inactive medium-size, coal-fired electric generating station located at 1111 West Cermak Road in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois. It was sited near the south branch of the Chicago River to provide access to water for steam and barge traffic for coal, and closed down in 2012.

Ebenezer Kinnersley was an English scientist, inventor and lecturer, specializing in the investigation of electricity.

The Glaspalast was a glass and iron exhibition building located in the Old botanical garden in Munich modeled after the Crystal Palace in London. The Glaspalast opened for the first General German Industrial Exhibition on 15 July 1854.

The Nordenfelt gun was a multiple-barrel organ gun that had a row of up to twelve barrels. It was fired by pulling a lever back and forth and ammunition was gravity fed through chutes for each barrel. It was produced in a number of different calibres up to 25 mm (0.98 in). Larger calibres were also used, but for these calibres the design simply permitted rapid manual loading rather than true automatic fire. This article covers the anti-personnel rifle-calibre gun.

A Shabbat lamp is a special lamp that has movable parts to expose or block out its light so it can be turned "on" or "off" while its power physically remains on. This enables the lamp's light to be controlled by those Shabbat observant Jews who accept this use, to make a room dark or light during Shabbat without actually switching the electrical power on or off, an act prohibited by Orthodox Judaism on both Shabbat and the Jewish Holidays.

James Graham (1745–1794) was a Scottish proponent of electrical cures, showman, and pioneer in sex therapy. A self-styled doctor, he was best known for his electro-magnetic musical Grand State Celestial Bed. Dismissed as a quack by medical experts, Graham apparently believed in the efficacy of his unusual treatments.

Franklin bells are an early demonstration of electric charge designed to work with a Leyden jar or a lightning rod. Franklin bells are only a qualitative indicator of electric charge and were used for simple demonstrations rather than research. The bells are an adaptation to the first device that converted electrical energy into mechanical energy in the form of continuous mechanical motion: in this case, the moving of a bell clapper back and forth between two oppositely charged bells.

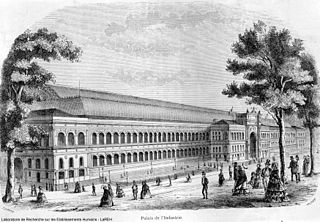

The first International Exposition of Electricity ran from 15 August 1881 through to 15 November 1881 at the Palais de l'Industrie on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, France. It served to display the advances in electrical technology since the small electrical display at the 1878 Universal Exposition. Exhibitors came from the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, as well as from France. As part of the exhibition, the first International Congress of Electricians presented numerous scientific and technical papers, including definitions of the standard practical units volt, ohm and ampere.

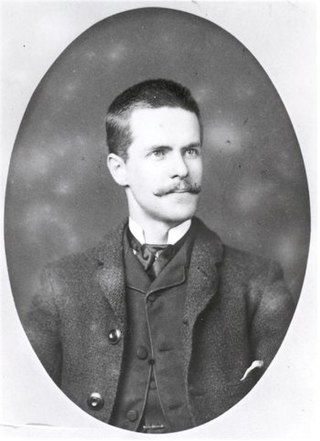

William Joseph Hammer was an American pioneer electrical engineer, aviator, and president of the Edison Pioneers.

Franklin's electrostatic machine is a high-voltage static electricity-generating device used by Benjamin Franklin in the mid-18th century for research into electrical phenomena. Its key components are a glass globe which turned on an axis via a crank, a cloth pad in contact with the spinning globe, a set of metal needles to conduct away the charge developed on the globe by its friction with the pad, and a Leyden jar – a high-voltage capacitor – to accumulate the charge. Franklin's experiments with the machine eventually led to new theories about electricity and inventing the lightning rod.

The Electro-Dynamic Light Company of New York was a lighting and electrical distribution company organized in 1878. The company held the patents for the first practical incandescent electric lamp and electrical distribution system of incandescent electric lighting. They also held a patent for an electric meter to measure the amount of electricity used. The inventions were those of Albon Man and William E. Sawyer. They gave the patent rights to the company, which they had formed with a group of businessmen. It was the first company in the world formally established to provided electric lighting and was the first company organized specifically to manufacture and sell incandescent electric light bulbs.

Edna Mosley was one of the first female professional architects in Britain, and was known for her designs for modern, labour-saving interiors, often aimed specifically at women.

References

- 1 2 Delbourgo, James, 1972- (2006). A most amazing scene of wonders : electricity and enlightenment in early America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02299-8. OCLC 64208386.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kinnersley, Ebenezer (1752). Notice is hereby given to the curious : that at the Court-House, in the Council-Chamber, is now to be exhibited, and continued from day to day, for a week or two ; a course of experiments, on the newly discovered electrical fire ... James Franklin. OCLC 25461550.

- ↑ Schaffer, Simon (March 1983). "Natural Philosophy and Public Spectacle in the Eighteenth Century". History of Science. 21 (1): 1–43. doi:10.1177/007327538302100101. ISSN 0073-2753. PMID 11611179. S2CID 38140290.

- ↑ Lemay, J. A. Leo (Joseph A. Leo), 1935-2008. (1964). Ebenezer Kinnersley, Franklin's friend. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-1757-7. OCLC 600290864.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Daston, Lorraine (2001). Wonders and the order of nature 1150-1750. Zone Books. ISBN 0-942299-91-4. OCLC 248541422.

- 1 2 3 4 Gooday, Graeme (2011), "Electricity and the Sociable Circulation of Fear and Fearlessness", Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Science, University of Chicago Press, pp. 203–228, doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226487298.003.0009, ISBN 978-0-226-48726-7

- ↑ "The international exhibition–view of the south-eastern transept". doi:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/arobinson/figure6.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)