Related Research Articles

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to other atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation of an atom in a chemical compound. Conceptually, the oxidation state may be positive, negative or zero. Beside nearly-pure ionic bonding, many covalent bonds exhibit a strong ionicity, making oxidation state a useful predictor of charge.

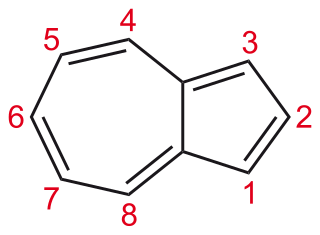

Azulene is an aromatic organic compound and an isomer of naphthalene. Naphthalene is colourless, whereas azulene is dark blue. The compound is named after its colour, as "azul" is Spanish for blue. Two terpenoids, vetivazulene (4,8-dimethyl-2-isopropylazulene) and guaiazulene (1,4-dimethyl-7-isopropylazulene), that feature the azulene skeleton are found in nature as constituents of pigments in mushrooms, guaiac wood oil, and some marine invertebrates.

In organic chemistry, hydroformylation, also known as oxo synthesis or oxo process, is an industrial process for the production of aldehydes from alkenes. This chemical reaction entails the net addition of a formyl group and a hydrogen atom to a carbon-carbon double bond. This process has undergone continuous growth since its invention: production capacity reached 6.6×106 tons in 1995. It is important because aldehydes are easily converted into many secondary products. For example, the resultant aldehydes are hydrogenated to alcohols that are converted to detergents. Hydroformylation is also used in speciality chemicals, relevant to the organic synthesis of fragrances and pharmaceuticals. The development of hydroformylation is one of the premier achievements of 20th-century industrial chemistry.

In chemistry, tautomers are structural isomers of chemical compounds that readily interconvert. The chemical reaction interconverting the two is called tautomerization. This conversion commonly results from the relocation of a hydrogen atom within the compound. The phenomenon of tautomerization is called tautomerism, also called desmotropism. Tautomerism is for example relevant to the behavior of amino acids and nucleic acids, two of the fundamental building blocks of life.

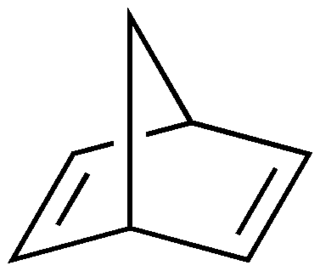

Norbornadiene is an organic compound and a bicyclic hydrocarbon. Norbornadiene is of interest as a metal-binding ligand, whose complexes are useful for homogeneous catalysis. It has been intensively studied owing to its high reactivity and distinctive structural property of being a diene that cannot isomerize. Norbornadiene is also a useful dienophile in Diels-Alder reactions.

A quintuple bond in chemistry is an unusual type of chemical bond, first reported in 2005 for a dichromium compound. Single bonds, double bonds, and triple bonds are commonplace in chemistry. Quadruple bonds are rarer and are currently known only among the transition metals, especially for Cr, Mo, W, and Re, e.g. [Mo2Cl8]4− and [Re2Cl8]2−. In a quintuple bond, ten electrons participate in bonding between the two metal centers, allocated as σ2π4δ4.

1,5-Cyclooctadiene is a cyclic hydrocarbon with the chemical formula C8H12, specifically [−(CH2)2−CH=CH−]2.

Dicobalt octacarbonyl is an organocobalt compound with composition Co2(CO)8. This metal carbonyl is used as a reagent and catalyst in organometallic chemistry and organic synthesis, and is central to much known organocobalt chemistry. It is the parent member of a family of hydroformylation catalysts. Each molecule consists of two cobalt atoms bound to eight carbon monoxide ligands, although multiple structural isomers are known. Some of the carbonyl ligands are labile.

In chemistry, a (redox) non-innocent ligand is a ligand in a metal complex where the oxidation state is not clear. Typically, complexes containing non-innocent ligands are redox active at mild potentials. The concept assumes that redox reactions in metal complexes are either metal or ligand localized, which is a simplification, albeit a useful one.

In coordination chemistry, the bite angle is the angle on a central atom between two bonds to a bidentate ligand. This ligand–metal–ligand geometric parameter is used to classify chelating ligands, including those in organometallic complexes. It is most often discussed in terms of catalysis, as changes in bite angle can affect not just the activity and selectivity of a catalytic reaction but even allow alternative reaction pathways to become accessible.

In organic chemistry, two molecules are valence isomers when they are constitutional isomers that can interconvert through pericyclic reactions.

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formula – that is, the same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism refers to the existence or possibility of isomers.

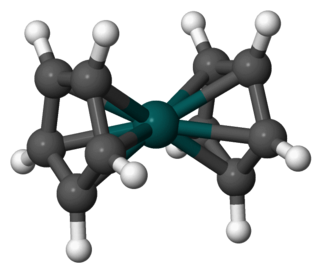

Rhodocene is a chemical compound with the formula [Rh(C5H5)2]. Each molecule contains an atom of rhodium bound between two planar aromatic systems of five carbon atoms known as cyclopentadienyl rings in a sandwich arrangement. It is an organometallic compound as it has (haptic) covalent rhodium–carbon bonds. The [Rh(C5H5)2] radical is found above 150 °C (302 °F) or when trapped by cooling to liquid nitrogen temperatures (−196 °C [−321 °F]). At room temperature, pairs of these radicals join via their cyclopentadienyl rings to form a dimer, a yellow solid.

Metal acetylacetonates are coordination complexes derived from the acetylacetonate anion (CH

3COCHCOCH−

3) and metal ions, usually transition metals. The bidentate ligand acetylacetonate is often abbreviated acac. Typically both oxygen atoms bind to the metal to form a six-membered chelate ring. The simplest complexes have the formula M(acac)3 and M(acac)2. Mixed-ligand complexes, e.g. VO(acac)2, are also numerous. Variations of acetylacetonate have also been developed with myriad substituents in place of methyl (RCOCHCOR′−). Many such complexes are soluble in organic solvents, in contrast to the related metal halides. Because of these properties, acac complexes are sometimes used as catalyst precursors and reagents. Applications include their use as NMR "shift reagents" and as catalysts for organic synthesis, and precursors to industrial hydroformylation catalysts. C

5H

7O−

2 in some cases also binds to metals through the central carbon atom; this bonding mode is more common for the third-row transition metals such as platinum(II) and iridium(III).

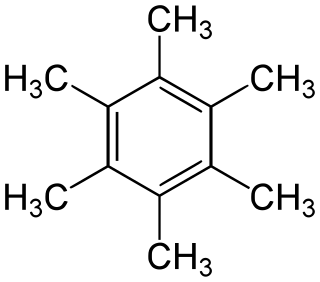

Hexamethylbenzene, also known as mellitene, is a hydrocarbon with the molecular formula C12H18 and the condensed structural formula C6(CH3)6. It is an aromatic compound and a derivative of benzene, where benzene's six hydrogen atoms have each been replaced by a methyl group. In 1929, Kathleen Lonsdale reported the crystal structure of hexamethylbenzene, demonstrating that the central ring is hexagonal and flat and thereby ending an ongoing debate about the physical parameters of the benzene system. This was a historically significant result, both for the field of X-ray crystallography and for understanding aromaticity.

The Buchner ring expansion is a two-step organic C-C bond forming reaction used to access 7-membered rings. The first step involves formation of a carbene from ethyl diazoacetate, which cyclopropanates an aromatic ring. The ring expansion occurs in the second step, with an electrocyclic reaction opening the cyclopropane ring to form the 7-membered ring.

The phosphaethynolate anion, also referred to as PCO, is the phosphorus-containing analogue of the cyanate anion with the chemical formula [PCO]− or [OCP]−. The anion has a linear geometry and is commonly isolated as a salt. When used as a ligand, the phosphaethynolate anion is ambidentate in nature meaning it forms complexes by coordinating via either the phosphorus or oxygen atoms. This versatile character of the anion has allowed it to be incorporated into many transition metal and actinide complexes but now the focus of the research around phosphaethynolate has turned to utilising the anion as a synthetic building block to organophosphanes.

Hexaphosphabenzene is a valence isoelectronic analogue of benzene and is expected to have a similar planar structure due to resonance stabilization and its sp2 nature. Although several other allotropes of phosphorus are stable, no evidence for the existence of P6 has been reported. Preliminary ab initio calculations on the trimerisation of P2 leading to the formation of the cyclic P6 were performed, and it was predicted that hexaphosphabenzene would decompose to free P2 with an energy barrier of 13−15.4 kcal mol−1, and would therefore not be observed in the uncomplexed state under normal experimental conditions. The presence of an added solvent, such as ethanol, might lead to the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds which may block the destabilizing interaction between phosphorus lone pairs and consequently stabilize P6. The moderate barrier suggests that hexaphosphabenzene could be synthesized from a [2+2+2] cycloaddition of three P2 molecules. Currently, this is a synthetic endeavour which remains to be conquered.

In organometallic chemistry, transition metal complexes of nitrite describes families of coordination complexes containing one or more nitrite ligands. Although the synthetic derivatives are only of scholarly interest, metal-nitrite complexes occur in several enzymes that participate in the nitrogen cycle.

Cobalt compounds are chemical compounds formed by cobalt with other elements.

References

- ↑ Bally, T. (2010). "Isomerism: The same but different" (PDF). Nature Chemistry. 2 (3): 165–166. Bibcode:2010NatCh...2..165B. doi:10.1038/nchem.564. PMID 21124473.

- ↑ Evangelio, E.; Ruiz-Molina, D. (2005). "Valence Tautomerism: New Challenges for Electroactive Ligands". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2005 (15): 2957. doi:10.1002/ejic.200500323.

- ↑ Jones, L. W. (1917). "Electromerism, A Case of Chemical Isomerism Resulting from a Difference in Distribution of Valence Electrons". Science. 46 (1195): 493–502. Bibcode:1917Sci....46..493J. doi:10.1126/science.46.1195.493. PMID 17818241.

- ↑ Puschmann, F.; Harmer, J.; Stein, D.; Rüegger, H.; De Bruin, B.; Grützmacher, H. (2010). "Electromeric rhodium radical complexes". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 49 (2): 385–389. doi:10.1002/anie.200903201. PMID 19957252.

- ↑ Puschmann, F.F.; Grützmacher, H.; de Bruin, B. (2010). "Rhodium(0) Metalloradicals in Binuclear C−H Activation". Journal of the American Chemical Society . 132 (1): 73–75. Bibcode:2010JAChS.132...73P. doi:10.1021/ja909022p. PMID 20000835.

- ↑ Müller, B.; Bally, T.; Gerson, F.; De Meijere, A.; Von Seebach, M. (2003). ""Electromers" of the tetramethyleneethane radical cation and their nonexistence in the octamethyl derivative: interplay of experiment and theory". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 125 (45): 13776–13783. Bibcode:2003JAChS.12513776M. doi:10.1021/ja037252v. PMID 14599217.