Related Research Articles

Feminist science fiction is a subgenre of science fiction focused on such feminist themes as: gender inequality, sexuality, race, economics, reproduction, and environment. Feminist SF is political because of its tendency to critique the dominant culture. Some of the most notable feminist science fiction works have illustrated these themes using utopias to explore a society in which gender differences or gender power imbalances do not exist, or dystopias to explore worlds in which gender inequalities are intensified, thus asserting a need for feminist work to continue.

Science fiction and fantasy serve as important vehicles for feminist thought, particularly as bridges between theory and practice. No other genres so actively invite representations of the ultimate goals of feminism: worlds free of sexism, worlds in which women's contributions are recognized and valued, worlds that explore the diversity of women's desire and sexuality, and worlds that move beyond gender.

Hortense Eugénie Cécile Bonaparte was Queen of Holland as the wife of King Louis Bonaparte. She was the stepdaughter of Emperor Napoléon I as the daughter of his first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais. Hortense later married Napoléon I's brother, Louis, making her Napoleon's sister-in-law. She became queen consort of Holland when Louis was made King of Holland in 1806. She and Louis had three sons: Napoléon-Charles Bonaparte; Napoleon III, Emperor of the French; and Louis II of Holland. She also had an illegitimate son, Charles, Duke of Morny, with her lover, the Comte de Flahaut.

This section of the timeline of United States history concerns events from 1790 to 1819.

Sarah Josepha Buell Hale was an American writer, activist, and editor of the most widely circulated magazine in the period before the Civil War, Godey's Lady's Book. She was the author of the nursery rhyme "Mary Had a Little Lamb". Hale famously campaigned for the creation of the American holiday known as Thanksgiving, and for the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument.

Ms. is an American feminist magazine co-founded in 1971 by journalist and social/political activist Gloria Steinem. It was the first national American feminist magazine. The original editors were Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Mary Thom, Patricia Carbine, Joanne Edgar, Nina Finkelstein, Mary Peacock, Margaret Sloan-Hunter, and Gloria Steinem. Beginning as a one-off insert in New York magazine in 1971, the first stand-alone issue of Ms. appeared in January 1972, with funding from New York editor Clay Felker. It was intended to appeal to a wide audience and featured articles about a variety of issues related to women and feminism. From July 1972 until 1987, it was published on a monthly basis. It now publishes quarterly.

Maria Anna Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi Levoy, better known as Elisa Bonaparte, was an imperial French princess and sister of Napoleon Bonaparte. She was Princess of Lucca and Piombino (1805-1814), Grand Duchess of Tuscany (1809-1814) and Countess of Compignano by appointment of her brother.

Sophie Cottin was a French writer whose novels were popular in the 19th century, and were translated into several different languages.

Natalie L. Wexler is an American education writer focusing on literacy and equity issues.

Diane Anderson-Minshall is an American journalist and author best known for writing about lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender subjects. She is the first female CEO of Pride Media. She is also the editorial director of The Advocate and Chill magazines, the editor-in-chief of HIV Plus magazine, while still contributing editor to OutTraveler. Diane co-authored the 2014 memoir Queerly Beloved about her relationship with her husband Jacob Anderson-Minshall throughout his gender transition.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin is an American author, journalist, lecturer, and social activist. She is a founding editor of Ms. magazine, the author of twelve books, and was an editorial consultant for the TV special Free to Be... You and Me for which she earned an Emmy.

Women in journalism are individuals who participate in journalism. As journalism became a profession, women were restricted by custom from access to journalism occupations, and faced significant discrimination within the profession. Nevertheless, women operated as editors, reporters, sports analysts and journalists even before the 1890s in some countries as far back as the 18th-century.

Eliza Parsons was an English Gothic novelist, best known for The Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) and The Mysterious Warning (1796). These are two of the seven Gothic titles recommended as reading by a character in Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey.

Alexandrine Bonaparte, Princess of Canino and Musignano was a French aristocrat and by marriage member of the French Imperial family.

Eliza Bisbee Duffey (1838–1898) was an American painter, author, poet, newspaper editor and printer, columnist, spiritualist, and feminist who published several books in defense of women's rights.

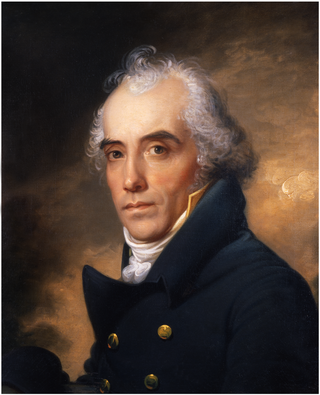

J. Maximilian M. Godefroy was a French-American architect. Godefroy was born in France and educated as a geographical/civil engineer. During the French Revolution he fought briefly on the Royalist side. Later, as an anti-Bonaparte activist, he was imprisoned in the fortress of Bellegarde and Château d'If then released about 1805 and allowed to come to the United States, settling in Baltimore, Maryland, where he became an instructor in drawing, art and military science at St. Mary's College, the Sulpician Seminary. By 1808, Godefroy had married Eliza Crawford Anderson, editor of her own periodical, the Observer and the niece of a wealthy Baltimore merchant.

Pearl Rivers was an American journalist and poet, and the first female editor of a major American newspaper. After being the literary editor of the New Orleans Daily Picayune, Rivers became the owner and publisher in 1876, after her elderly husband died. In 1880, she took over as managing editor, where she continued until her death in 1896.

Caroline M. Sawyer was a 19th-century American poet, writer, and editor. Her writings ranged through a wide variety of themes. Born in 1812, in Massachusetts, she began composing verse at an early age, but published little till after her marriage. Thereafter, she wrote much for various reviews and other miscellanies, besides several volumes of tales, sketches, and essays. She also made numerous translations from German literature, in prose and verse, in which she evinced an appreciation of the original. Sawyer's poems were numerous, sufficient for several volumes, though they were not published as a collection.

Martha Violet Ball was a 19th-century American educator, philanthropist, activist, writer, and editor. Ball and her sister, Lucy, undertook the work of opening a school for young African American girls in the West End of Boston. In the same year, 1833, she assisted in the organization of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, of which she and Lucy held leadership roles. Her work among unfortunate women and girls led to the formation of the New England Female Moral Reform Society, with which she was from its beginning connected as Secretary and Manager. For twenty-five years, she was joint-editor of its organ, the Home Guardian, and was also affiliated in its department, "The Children's Fireside". She was a constituent member of the Ladies' Baptist Bethel Society, first as its Secretary and for thirty years its President. Ball was the first President of the Woman's Union Missionary Society of America for Heathen Lands, and a charter member of the New England Woman's Press Association. She was the author of several small, popular books.

The Humming Bird, or Herald of Taste was an American women's magazine published in 1798. It is the first known magazine in the United States edited by a woman, for women.

References

- Branson, Susan (2008).Dangerous to Know: Women, Crime, and Notoriety in the Early Republic. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Cottin, Sophie (Margaret Cohen trans., after Eliza Godefroy)(1799/2002). Claire d'Albe: An English Translation. The Modern Language Association of America.

- Okker, Patricia (1995). Our Sister Editors: Sarah J. Hale and the Tradition of Nineteenth-Century American Women Editors. University of Georgia Press.

- The Observer, Baltimore, January–December 1807.

- Wells, Jonathan Daniel (2008). "A Voice in the Nation: Women Journalists in the Early Nineteenth-Century South," American Nineteenth-Century History, 9, p. 166.

- Wexler, Natalie (2010). "'What Manner of Woman Our Female Editor May Be': Eliza Crawford Anderson and the Baltimore Observer, 1806-1807" (PDF). Vol. 105, no. 2. Maryland Historical Magazine. p. 100.

- Wood, Gordon (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815.Oxford University Press.