Alexios III Angelos, Latinized as Alexius III Angelus, was Byzantine Emperor from March 1195 to 17/18 July 1203. He reigned under the name Alexios Komnenos associating himself with the Komnenos dynasty. A member of the extended imperial family, Alexios came to the throne after deposing, blinding and imprisoning his younger brother Isaac II Angelos. The most significant event of his reign was the attack of the Fourth Crusade on Constantinople in 1203, on behalf of Alexios IV Angelos. Alexios III took over the defence of the city, which he mismanaged, and then fled the city at night with one of his three daughters. From Adrianople, and then Mosynopolis, he attempted unsuccessfully to rally his supporters, only to end up a captive of Marquis Boniface of Montferrat. He was ransomed and sent to Asia Minor where he plotted against his son-in-law Theodore I Laskaris, but was eventually captured and spent his last days confined to the Monastery of Hyakinthos in Nicaea, where he died.

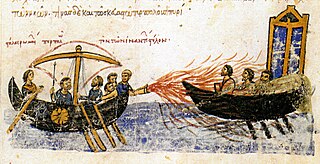

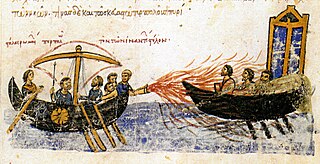

Greek fire was an incendiary chemical weapon manufactured in and used by the Eastern Roman Empire from the seventh through the fourteenth centuries. The recipe for Greek fire was a closely-guarded state state secret, but historians speculate it may have been using a combination of pine resin, naphtha, quicklime, calcium phosphide, sulfur, or niter. Roman sailors would toss grenades loaded with Greek fire onto enemy ships or spray it from tubes. Its ability to burn on water made it an effective and destructive naval incendiary weapon, and rival powers tried unsuccessfully to copy the material.

Sir William Gerald Golding was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel Lord of the Flies (1954), he published another twelve volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 1980, he was awarded the Booker Prize for Rites of Passage, the first novel in what became his sea trilogy, To the Ends of the Earth. He was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Cymbeline, also known as The Tragedie of Cymbeline or Cymbeline, King of Britain, is a play by William Shakespeare set in Ancient Britain and based on legends that formed part of the Matter of Britain concerning the early historical Celtic British King Cunobeline. Although it is listed as a tragedy in the First Folio, modern critics often classify Cymbeline as a romance or even a comedy. Like Othello and The Winter's Tale, it deals with the themes of innocence and jealousy. While the precise date of composition remains unknown, the play was certainly produced as early as 1611.

Military technology is the application of technology for use in warfare. It comprises the kinds of technology that are distinctly military in nature and not civilian in application, usually because they lack useful or legal civilian applications, or are dangerous to use without appropriate military training.

John Ericsson was a Swedish-American inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Alastair George Bell Sim, CBE was a Scottish character actor who began his theatrical career at the age of thirty and quickly became established as a popular West End performer, remaining so until his death in 1976. Starting in 1935, he also appeared in more than fifty British films, including an iconic adaptation of Charles Dickens’ novella A Christmas Carol, released in 1951 as Scrooge in Great Britain and as A Christmas Carol in the United States. Though an accomplished dramatic actor, he is often remembered for his comically sinister performances.

A safety valve is a valve that acts as a fail-safe. An example of safety valve is a pressure relief valve (PRV), which automatically releases a substance from a boiler, pressure vessel, or other system, when the pressure or temperature exceeds preset limits. Pilot-operated relief valves are a specialized type of pressure safety valve. A leak tight, lower cost, single emergency use option would be a rupture disk.

Theodora, sometimes called Theodora the Armenian or Theodora the Blessed, was Byzantine empress as the wife of Byzantine emperor Theophilos from 830 to 842 and regent for the couple's young son Michael III, after the death of Theophilos, from 842 to 856. She is sometimes counted as an empress regnant, who actually ruled in her own right, rather than just a regent. Theodora is most famous for bringing an end to the second Byzantine Iconoclasm (814–843), an act for which she is recognized as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Though her reign saw the loss of most of Sicily and failure to retake Crete, Theodora's foreign policy was otherwise highly successful; by 856, the Byzantine Empire had gained the upper hand over both the Bulgarian Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate, and the Slavic tribes in the Peloponnese had been forced to pay tribute, all without decreasing the imperial gold reserve.

The Exposition Universelle of 1878, better known in English as the 1878 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 1 May to 10 November 1878, to celebrate the recovery of France after the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War. It was the third of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937.

A thimble is a small pitted cup worn on the finger that protects it from being pricked or poked by a needle while sewing. The Old English word þȳmel, the ancestor of thimble, is derived from Old English þūma, the ancestor of the English word thumb.

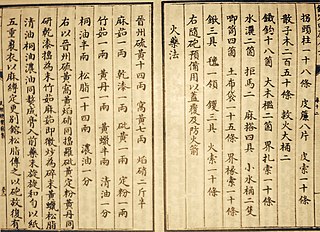

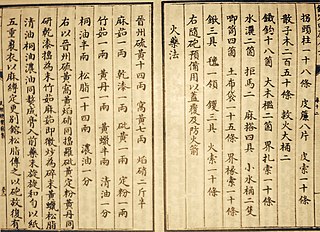

The Four Great Inventions are inventions from ancient China that are celebrated in Chinese culture for their historical significance and as symbols of ancient China's advanced science and technology. They are the compass, gunpowder, papermaking and printing.

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 was made between representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Kingdom of Joseon in 1876. Negotiations were concluded on February 26, 1876.

Jacob Perkins was an American inventor, mechanical engineer and physicist based in the United Kingdom. Born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, Perkins was apprenticed to a goldsmith. He soon made himself known with a variety of useful mechanical inventions and eventually had twenty-one American and nineteen English patents. He is known as the father of the refrigerator. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1813 and a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1819.

The Scorpion God is a collection of three novellas by William Golding published in 1971. They are all set in the distant past: "The Scorpion God" in ancient Egypt, "Clonk Clonk" in pre-historic Africa, and "Envoy Extraordinary" in ancient Rome. A draft of "The Scorpion God" had been written but abandoned in 1964, "Clonk Clonk" was newly written for the book, and "Envoy Extraordinary" had been published before, in 1956. "Envoy Extraordinary" became a play called The Brass Butterfly which was performed first in Oxford and later in London and New York.

The Wujing Zongyao, sometimes rendered in English as the Complete Essentials for the Military Classics, is a Chinese military compendium written from around 1040 to 1044.

A Byzantine-Mongol Alliance occurred during the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century between the Byzantine Empire and the Mongol Empire. Byzantium attempted to maintain friendly relations with both the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate realms, who were often at war with each other. The alliance involved numerous exchanges of presents, military collaboration and marital links, but dissolved in the middle of the 14th century.

The Hon. Sir John Duncan Bligh KCB, DL was a British diplomat.

Sir Thomas Tassell Grant KCB FRS was a notable inventor in the 19th century.

Michael Stryphnos was a high-ranking Byzantine official under the Angeloi emperors.