Related Research Articles

An evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) is a strategy that is impermeable when adopted by a population in adaptation to a specific environment, that is to say it cannot be displaced by an alternative strategy which may be novel or initially rare. Introduced by John Maynard Smith and George R. Price in 1972/3, it is an important concept in behavioural ecology, evolutionary psychology, mathematical game theory and economics, with applications in other fields such as anthropology, philosophy and political science.

Frequentist probability or frequentism is an interpretation of probability; it defines an event's probability as the limit of its relative frequency in infinitely many trials . Probabilities can be found by a repeatable objective process. The continued use of frequentist methods in scientific inference, however, has been called into question.

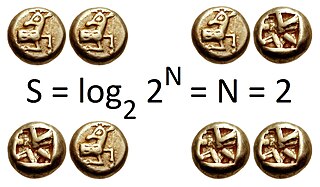

In information theory, the entropy of a random variable quantifies the average level of uncertainty or information associated with the variable's potential states or possible outcomes. This measures the expected amount of information needed to describe the state of the variable, considering the distribution of probabilities across all potential states. Given a discrete random variable , which takes values in the set and is distributed according to , the entropy is where denotes the sum over the variable's possible values. The choice of base for , the logarithm, varies for different applications. Base 2 gives the unit of bits, while base e gives "natural units" nat, and base 10 gives units of "dits", "bans", or "hartleys". An equivalent definition of entropy is the expected value of the self-information of a variable.

Probability is the branch of mathematics and statistics concerning events and numerical descriptions of how likely they are to occur. The probability of an event is a number between 0 and 1; the larger the probability, the more likely an event is to occur. A simple example is the tossing of a fair (unbiased) coin. Since the coin is fair, the two outcomes are both equally probable; the probability of "heads" equals the probability of "tails"; and since no other outcomes are possible, the probability of either "heads" or "tails" is 1/2.

The word probability has been used in a variety of ways since it was first applied to the mathematical study of games of chance. Does probability measure the real, physical, tendency of something to occur, or is it a measure of how strongly one believes it will occur, or does it draw on both these elements? In answering such questions, mathematicians interpret the probability values of probability theory.

Probability theory or probability calculus is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expressing it through a set of axioms. Typically these axioms formalise probability in terms of a probability space, which assigns a measure taking values between 0 and 1, termed the probability measure, to a set of outcomes called the sample space. Any specified subset of the sample space is called an event.

Statistics is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a scientific, industrial, or social problem, it is conventional to begin with a statistical population or a statistical model to be studied. Populations can be diverse groups of people or objects such as "all people living in a country" or "every atom composing a crystal". Statistics deals with every aspect of data, including the planning of data collection in terms of the design of surveys and experiments.

A statistical hypothesis test is a method of statistical inference used to decide whether the data sufficiently supports a particular hypothesis. A statistical hypothesis test typically involves a calculation of a test statistic. Then a decision is made, either by comparing the test statistic to a critical value or equivalently by evaluating a p-value computed from the test statistic. Roughly 100 specialized statistical tests have been defined.

In philosophy, Occam's razor is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony. Attributed to William of Ockham, a 14th-century English philosopher and theologian, it is frequently cited as Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem, which translates as "Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity", although Occam never used these exact words. Popularly, the principle is sometimes paraphrased as "The simplest explanation is usually the best one."

Rudolf Carnap was a German-language philosopher who was active in Europe before 1935 and in the United States thereafter. He was a major member of the Vienna Circle and an advocate of logical positivism.

Uncertainty or incertitude refers to epistemic situations involving imperfect or unknown information. It applies to predictions of future events, to physical measurements that are already made, or to the unknown. Uncertainty arises in partially observable or stochastic environments, as well as due to ignorance, indolence, or both. It arises in any number of fields, including insurance, philosophy, physics, statistics, economics, finance, medicine, psychology, sociology, engineering, metrology, meteorology, ecology and information science.

Synchronicity is a concept introduced by analytical psychiatrist Carl Jung to describe events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection. Jung held this was a healthy function of the mind, that can become harmful within psychosis.

Scientific evidence is evidence that serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis, although scientists also use evidence in other ways, such as when applying theories to practical problems. Such evidence is expected to be empirical evidence and interpretable in accordance with the scientific method. Standards for scientific evidence vary according to the field of inquiry, but the strength of scientific evidence is generally based on the results of statistical analysis and the strength of scientific controls.

The principle of indifference is a rule for assigning epistemic probabilities. The principle of indifference states that in the absence of any relevant evidence, agents should distribute their credence equally among all the possible outcomes under consideration.

Occasionalism is a philosophical doctrine about causation which says that created substances cannot be efficient causes of events. Instead, all events are taken to be caused directly by God. The doctrine states that the illusion of efficient causation between mundane events arises out of God's causing of one event after another. However, there is no necessary connection between the two: it is not that the first event causes God to cause the second event: rather, God first causes one and then causes the other.

The classical definition or interpretation of probability is identified with the works of Jacob Bernoulli and Pierre-Simon Laplace. As stated in Laplace's Théorie analytique des probabilités,

The mathematical expressions for thermodynamic entropy in the statistical thermodynamics formulation established by Ludwig Boltzmann and J. Willard Gibbs in the 1870s are similar to the information entropy by Claude Shannon and Ralph Hartley, developed in the 1940s.

Equiprobability is a property for a collection of events that each have the same probability of occurring. In statistics and probability theory it is applied in the discrete uniform distribution and the equidistribution theorem for rational numbers. If there are events under consideration, the probability of each occurring is

The Foundations of Statistics are the mathematical and philosophical bases for statistical methods. These bases are the theoretical frameworks that ground and justify methods of statistical inference, estimation, hypothesis testing, uncertainty quantification, and the interpretation of statistical conclusions. Further, a foundation can be used to explain statistical paradoxes, provide descriptions of statistical laws, and guide the application of statistics to real-world problems.

Bayesian epistemology is a formal approach to various topics in epistemology that has its roots in Thomas Bayes' work in the field of probability theory. One advantage of its formal method in contrast to traditional epistemology is that its concepts and theorems can be defined with a high degree of precision. It is based on the idea that beliefs can be interpreted as subjective probabilities. As such, they are subject to the laws of probability theory, which act as the norms of rationality. These norms can be divided into static constraints, governing the rationality of beliefs at any moment, and dynamic constraints, governing how rational agents should change their beliefs upon receiving new evidence. The most characteristic Bayesian expression of these principles is found in the form of Dutch books, which illustrate irrationality in agents through a series of bets that lead to a loss for the agent no matter which of the probabilistic events occurs. Bayesians have applied these fundamental principles to various epistemological topics but Bayesianism does not cover all topics of traditional epistemology. The problem of confirmation in the philosophy of science, for example, can be approached through the Bayesian principle of conditionalization by holding that a piece of evidence confirms a theory if it raises the likelihood that this theory is true. Various proposals have been made to define the concept of coherence in terms of probability, usually in the sense that two propositions cohere if the probability of their conjunction is higher than if they were neutrally related to each other. The Bayesian approach has also been fruitful in the field of social epistemology, for example, concerning the problem of testimony or the problem of group belief. Bayesianism still faces various theoretical objections that have not been fully solved.

References

- ↑ "Socrates and Berkeley Scholars Web Hosting Services Have Been Retired | Web Platform Services". web.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- ↑ Wright, J. N. (January 1951). "Book Reviews". The Philosophical Quarterly. 1 (2): 179–180. doi:10.2307/2216737. JSTOR 2216737.

- ↑ Jensen, A.; la Cour-Harbo, A. (2001). "The Discrete Wavelet Transform via Lifting". Ripples in Mathematics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 11–24. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-56702-5_3. ISBN 978-3-540-41662-3.