Related Research Articles

The Gracchi brothers were two brothers who lived during the beginning of the late Roman Republic: Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus. They served in the plebeian tribunates of 133 BC and 122–121 BC, respectively. They have been received as well-born and eloquent advocates for social reform who were both killed by a reactionary political system; their terms in the tribunate precipitated a series of domestic crises which are viewed as unsettling the Roman Republic and contributing to its collapse.

The Roman Republic was the era of classical Roman civilization beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom and ending in 27 BC with the establishment of the Roman Empire. During this period, Rome's control expanded from the city's immediate surroundings to hegemony over the entire Mediterranean world.

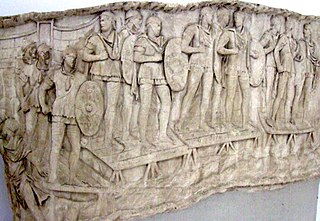

The Roman legion, the largest military unit of the Roman army, was composed of Roman citizens serving as legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. After the Marian reforms in 107 BC the legions were formed of 5200 men and were restructured around 10 cohorts, the first cohort being double strength. This structure persisted throughout the Principate and Middle Empire, before further changes in the fourth century resulted in new formations of around 1000 men.

The equites constituted the second of the property-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an eques.

Aerarium, from aes + -ārium, was the name given in Ancient Rome to the public treasury, and in a secondary sense to the public finances.

The Marian reforms were putative changes to the composition and operation of the Roman army during the late Roman republic usually attributed to Gaius Marius. The most important of those putative changes concerned the altering of the socio-economic background of the soldiery. Other changes were supposed to have included the introduction of the cohort; the institution of a single form of heavy infantry with uniform equipment; the universal adoption of the eagle standard; and the abolition of the citizen cavalry. It was commonly believed that Marius changed the soldiers' socio-economic background by allowing citizens without property to join the Roman army, a process called "proletarianisation". This was then supposed to have created a semi-professional class of soldiers motivated by land grants which in turn became clients of their generals, who then used them to overthrow the republic.

Lucius Aurelius Cotta was a Roman politician from an old noble family who held the offices of praetor, consul and censor. Both his father and grandfather of the same name had been consuls, and his two brothers, Gaius Aurelius Cotta and Marcus Aurelius Cotta, preceded him as consul in 75 and 74 BC respectively. His sister, Aurelia, was married to Gaius Julius Caesar, brother-in-law to Gaius Marius and possibly Lucius Cornelius Sulla, and they were the parents of the famous general and eventual dictator, Gaius Julius Caesar.

A consul was the highest elected public official of the Roman Republic. Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the cursus honorum—an ascending sequence of public offices to which politicians aspired—after that of the censor, which was reserved for former consuls. Each year, the Centuriate Assembly elected two consuls to serve jointly for a one-year term. The consuls alternated each month holding fasces when both were in Rome. A consul's imperium extended over Rome and all its provinces.

Marcus Valerius Laevinus was a Roman consul and commander who rose to prominence during the Second Punic War and corresponding First Macedonian War. A member of the gens Valeria, an old patrician family believed to have migrated to Rome under the Sabine king T. Tatius, Laevinus played an integral role in the containment of the Macedonian threat.

The auxilia were introduced as non-citizen troops attached to the citizen legions by Augustus after his reorganisation of the Imperial Roman army from 27 BC. By the 2nd century, the Auxilia contained the same number of infantry as the legions and, in addition, provided almost all of the Roman army's cavalry and more specialised troops. The auxilia thus represented three-fifths of Rome's regular land forces at that time. Like their legionary counterparts, auxiliary recruits were mostly volunteers, not conscripts.

Marcus Livius Drusus was a Roman politician and reformer. He is most famous for his legislative programme during his term as tribune of the plebs in 91 BC. During his year in office, Drusus proposed wide-ranging legislative reforms, including offering citizenship to Rome's Italian allies.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of uncodified norms and customs which, together with various written laws, guided the procedural governance of the Roman Republic. The constitution emerged from that of the Roman kingdom, evolved substantively and significantly – almost to the point of unrecognisability – over the almost five hundred years of the republic. The collapse of republican government and norms beginning in 133 BC would lead to the rise of Augustus and his principate.

Roman cavalry refers to the horse-mounted forces of the Roman army throughout the regal, republican, and imperial eras.

The Roman army of the mid-Republic, also called the manipular Roman army or the Polybian army, refers to the armed forces deployed by the mid-Roman Republic, from the end of the Samnite Wars to the end of the Social War. The first phase of this army, in its manipular structure, is described in detail in the Histories of the ancient Greek historian Polybius, writing before 146 BC.

The Roman army of the late Republic refers to the armed forces deployed by the late Roman Republic, from the beginning of the first century BC until the establishment of the Imperial Roman army by Augustus in 30 BC.

In Roman law during the Republic, calumnia was the willful bringing of a false accusation, that is, malicious prosecution. The English word "calumny" derives from the Latin.

The Servian constitution was one of the earliest forms of military and political organization used during The Roman Republic. Most of the reforms extended voting rights to certain groups, in particular to Rome's citizen-commoners who were minor landholders or otherwise landless citizens hitherto disqualified from voting by ancestry, status or ethnicity, as distinguished from the hereditary patricians. The reforms thus redefined the fiscal and military obligations of all Roman citizens. The constitution introduced two elements into the Roman system of government: a census of every male citizen, in order to establish his wealth, tax liabilities, military obligation, and the weight of his vote; and the comitia centuriata, an assembly with electoral, legislative and judicial powers. Both institutions were foundational for Roman republicanism.

The Lex Aurelia iudicaiaria was a Roman law, introduced by the praetor Lucius Aurelius Cotta in 70 BC. The law defined the composition of the jury of the court investigating extortion, corruption and misconduct in office, the perpetual quaestio de repetundis. Previously exclusive to senators, the juries henceforth included equites and tribuni aerarii.

A quaestio perpetua was a permanent jury court in the Roman republic. The first was established by the lex Calpurnia de repetundis in 149 BC to try cases on corruption and extortion. More were established in following years to hear cases on various crimes, such as maiestas (treason), ambitus, peculatus, and vis. Unlike the older trials before a popular assembly, which had to be convoked for that purpose by a sitting magistrate, the courts were always open and any citizen could bring charges.

References

- ↑ Davenport 2019, pp. 5 (ordo), 36–37.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 35 (qualification), 37 (subsidy).

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 34, citing Polyb., 6.19.1–4.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, pp. 8, 11, 14.

- ↑ Eg Rosenstein 2016 , p. 83.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Davenport 2019 , p. 37 n. 66, citing Rosenstein, Nathan (2008). "Aristocrats and agriculture in the middle and late republic". Journal of Roman Studies. 98: 1–26.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, pp. 37–38, citing Polyb., 2.24.

- ↑ Brunt 1988, pp. 144–46.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, pp. 37–38; Rosenstein 2007, p. 135.

- ↑ Rosenstein 2016, p. 83.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 54.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 57, noting service by a society of publicani in Spain in the 90s BC.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 68.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 107, noting disagreement as to whether the tribuni aerarii were equivalent to or otherwise a subset of the equites equo squo; Brunt 1988, pp. 146, 211.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 252.

- ↑ Davenport 2019, p. 224.

- ↑ Davenport 2019 , p. 207, citing Mommsen, Theodor (1887–1888). Römisches Staatsrecht. Vol. 3. pp. 489–91.

- ↑ Millar & Burton 2012.