Related Research Articles

Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior. Since the early 2020s, the term has seen a revival in bioethical discussions on the usage of new technologies such as CRISPR and genetic screening, with ongoing debate around whether these technologies should be considered eugenics or not.

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of various kinds, including those characterized by close kinship relations. By the 17th century, the term began to refer to physical (phenotypical) traits, and then later to national affiliations. Modern science regards race as a social construct, an identity which is assigned based on rules made by society. While partly based on physical similarities within groups, race does not have an inherent physical or biological meaning. The concept of race is foundational to racism, the belief that humans can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another.

Transhumanism is a philosophical and intellectual movement that advocates the enhancement of the human condition by developing and making widely available sophisticated technologies that can greatly enhance longevity, cognition, and well-being.

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biology, he was one of the founders of neo-Darwinism. He served in the Great War, and obtained the rank of captain. Despite his lack of an academic degree in the field, he taught biology at the University of Cambridge, the Royal Institution, and University College London. Renouncing his British citizenship, he became an Indian citizen in 1961 and worked at the Indian Statistical Institute for the rest of his life.

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who almost single-handedly created the foundations for modern statistical science" and "the single most important figure in 20th century statistics". In genetics, Fisher was the one to most comprehensively combine the ideas of Gregor Mendel and Charles Darwin, as his work used mathematics to combine Mendelian genetics and natural selection; this contributed to the revival of Darwinism in the early 20th-century revision of the theory of evolution known as the modern synthesis. For his contributions to biology, Richard Dawkins declared Fisher to be the greatest of Darwin's successors. He is also considered one of the founding fathers of Neo-Darwinism. According to statistician Jeffrey T. Leek, Fisher is the most influential scientist of all time based off the number of citations of his contributions.

Hermann Joseph Muller was an American geneticist who was awarded the 1946 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, "for the discovery that mutations can be induced by X-rays". Muller warned of long-term dangers of radioactive fallout from nuclear war and nuclear testing, which resulted in greater public scrutiny of these practices.

Joshua Lederberg, ForMemRS was an American molecular biologist known for his work in microbial genetics, artificial intelligence, and the United States space program. He was 33 years old when he won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and exchange genes. He shared the prize with Edward Tatum and George Beadle, who won for their work with genetics.

Pathophysiology is a branch of study, at the intersection of pathology and physiology, concerning disordered physiological processes that cause, result from, or are otherwise associated with a disease or injury. Pathology is the medical discipline that describes conditions typically observed during a disease state, whereas physiology is the biological discipline that describes processes or mechanisms operating within an organism. Pathology describes the abnormal or undesired condition, whereas pathophysiology seeks to explain the functional changes that are occurring within an individual due to a disease or pathologic state.

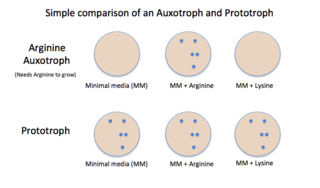

Auxotrophy is the inability of an organism to synthesize a particular organic compound required for its growth. An auxotroph is an organism that displays this characteristic; auxotrophic is the corresponding adjective. Auxotrophy is the opposite of prototrophy, which is characterized by the ability to synthesize all the compounds needed for growth.

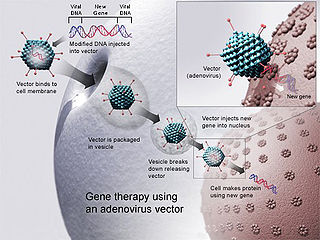

Human genetic enhancement or human genetic engineering refers to human enhancement by means of a genetic modification. This could be done in order to cure diseases, prevent the possibility of getting a particular disease, to improve athlete performance in sporting events, or to change physical appearance, metabolism, and even improve physical capabilities and mental faculties such as memory and intelligence. These genetic enhancements may or may not be done in such a way that the change is heritable.

The American Eugenics Society (AES) was a pro-eugenics organization dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of human populations". It endorsed the study and practice of Eugenics in the United States. Its original name as the American Eugenics Society lasted from 1922 to 1973, but the group changed their name after open use of the term "eugenics" became disfavored; it was known as the Society for the Study of Social Biology from 1973-2008, and the Society for Biodemography and Social Biology from 2008–2019. The Society was disbanded in 2019.

Medical genetics is the branch of medicine that involves the diagnosis and management of hereditary disorders. Medical genetics differs from human genetics in that human genetics is a field of scientific research that may or may not apply to medicine, while medical genetics refers to the application of genetics to medical care. For example, research on the causes and inheritance of genetic disorders would be considered within both human genetics and medical genetics, while the diagnosis, management, and counselling people with genetic disorders would be considered part of medical genetics.

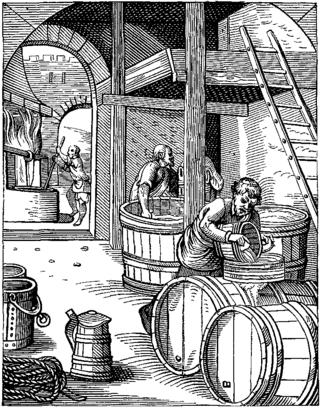

Biotechnology is the application of scientific and engineering principles to the processing of materials by biological agents to provide goods and services. From its inception, biotechnology has maintained a close relationship with society. Although now most often associated with the development of drugs, historically biotechnology has been principally associated with food, addressing such issues as malnutrition and famine. The history of biotechnology begins with zymotechnology, which commenced with a focus on brewing techniques for beer. By World War I, however, zymotechnology would expand to tackle larger industrial issues, and the potential of industrial fermentation gave rise to biotechnology. However, both the single-cell protein and gasohol projects failed to progress due to varying issues including public resistance, a changing economic scene, and shifts in political power.

Yuri Aleksandrovich Filipchenko, sometimes Philipchenko was a Russian entomologist who coined the terms microevolution and macroevolution, as well as the mentor of geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky. Though he himself was an orthogeneticist, he was one of the first scientists to incorporate the laws of Mendel into evolutionary theory and thus had a great influence on The Modern Synthesis. He established a genetics laboratory in Leningrad undertaking experimental work with Drosophila melanogaster. Theodosius Dobzhansky worked with him from 1924. Filipchenko is also known for his work in Soviet eugenics, though his work in the subject would later result in his public denunciation due to the rise of Stalinism and increased criticisms that eugenics represented bourgeois science.

Esther Miriam Zimmer Lederberg was an American microbiologist and a pioneer of bacterial genetics. She discovered the bacterial virus lambda phage and the bacterial fertility factor F, devised the first implementation of replica plating, and furthered the understanding of the transfer of genes between bacteria by specialized transduction.

The Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment was an experimental demonstration by Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty that, in 1944, reported that DNA is the substance that causes bacterial transformation, in an era when it had been widely believed that it was proteins that served the function of carrying genetic information. It was the culmination of research in the 1930s and early 20th century at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research to purify and characterize the "transforming principle" responsible for the transformation phenomenon first described in Griffith's experiment of 1928: killed Streptococcus pneumoniae of the virulent strain type III-S, when injected along with living but non-virulent type II-R pneumococci, resulted in a deadly infection of type III-S pneumococci. In their paper "Studies on the Chemical Nature of the Substance Inducing Transformation of Pneumococcal Types: Induction of Transformation by a Desoxyribonucleic Acid Fraction Isolated from Pneumococcus Type III", published in the February 1944 issue of the Journal of Experimental Medicine, Avery and his colleagues suggest that DNA, rather than protein as widely believed at the time, may be the hereditary material of bacteria, and could be analogous to genes and/or viruses in higher organisms.

The State Institute for Racial Biology was a Swedish governmental research institute founded in 1922 with the stated purpose of studying eugenics and human genetics. It was the most prominent institution for the study of "racial science" in Sweden. It was located in Uppsala. In 1958, it was renamed to the State Institute for Human Genetics and is today incorporated as a department of Uppsala University.

"Sickle Cell Anemia, a Molecular Disease" is a 1949 scientific paper by Linus Pauling, Harvey A. Itano, Seymour J. Singer and Ibert C. Wells that established sickle-cell anemia as a genetic disease in which affected individuals have a different form of the metalloprotein hemoglobin in their blood. The paper, published in the November 25, 1949 issue of Science, reports a difference in electrophoretic mobility between hemoglobin from healthy individuals and those with sickle-cell anemia, with those with sickle cell trait having a mixture of the two types. The paper suggests that the difference in electrophoretic mobility is probably due to a different number of ionizable amino acid residues in the protein portion of hemoglobin, and that this change in molecular structure is responsible for the sickling process. It also reports the genetic basis for the disease, consistent with the simultaneous genealogical study by James V. Neel: those with sickle-cell anemia are homozygous for the disease gene, while heterozygous individuals exhibit the usually asymptomatic condition of sickle cell trait.

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century. The cause became increasingly promoted by intellectuals of the Progressive Era.

Aspects of genetics including mutation, hybridisation, cloning, genetic engineering, and eugenics have appeared in fiction since the 19th century.

References

- ↑ Bud, Robert. The Uses of Life: A History of Biotechnology, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 167

- ↑ Khanna, Pragya. Essentials of Genetics, I. K. International Pvt Ltd, 2010, p. 367

- ↑ Lederberg, Joshua. "Molecular Biology, Eugenics and Euphenics", Nature 63(198), p. 428

- ↑ Minkoff, Eli and Baker, Pamela. Biology Today: An Issues Approach, Taylor & Francis, 2000, p. 115

- ↑ Pai, Anna. Foundations of Genetics: A Science for Society, McGraw-Hill, 1974, p. 408

- ↑ Burdyuzha, Vladimir. The Future of the Universe and the Future of our Civilization, World Scientific, 2000, pp. 261−263

- ↑ Guttman, Burton. Genetics: The Code of Life, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2011, p. 101

- ↑ Maxson, Linda and Daugherty, Charles. Genetics: A Human Perspective, W.C.Brown, 1992, p. 391