Related Research Articles

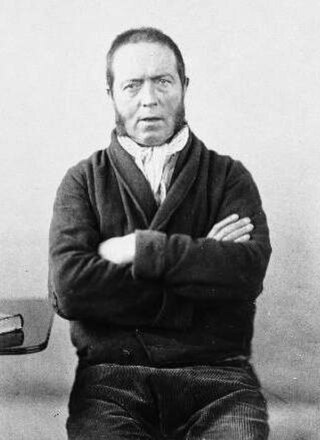

The M'Naghten rule is any variant of the 1840s jury instruction in a criminal case when there is a defence of insanity:

that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

In a legal dispute, one party has the burden of proof to show that they are correct, while the other party has no such burden and is presumed to be correct. The burden of proof requires a party to produce evidence to establish the truth of facts needed to satisfy all the required legal elements of the dispute.

In a civil proceeding or criminal prosecution under the common law or under statute, a defendant may raise a defense in an effort to avert civil liability or criminal conviction. A defense is put forward by a party to defeat a suit or action brought against the party, and may be based on legal grounds or on factual claims.

Beyond (a) reasonable doubt is a legal standard of proof required to validate a criminal conviction in most adversarial legal systems. It is a higher standard of proof than the standard of balance of probabilities commonly used in civil cases because the stakes are much higher in a criminal case: a person found guilty can be deprived of liberty, or in extreme cases, life, as well as suffering the collateral consequences and social stigma attached to a conviction. The prosecution is tasked with providing evidence that establishes guilt beyond a reasonable doubt in order to get a conviction; albeit prosecution may fail to complete such task, the trier-of-fact's acceptance that guilt has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt will in theory lead to conviction of the defendant. A failure for the trier-of-fact to accept that the standard of proof of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt has been met thus entitles the accused to an acquittal. This standard of proof is widely accepted in many criminal justice systems, and its origin can be traced to Blackstone's ratio, "It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer."

Woolmington v DPP [1935] AC 462 is a landmark House of Lords case, where the presumption of innocence was re-consolidated.

In trust law, a constructive trust is an equitable remedy imposed by a court to benefit a party that has been wrongfully deprived of its rights due to either a person obtaining or holding a legal property right which they should not possess due to unjust enrichment or interference, or due to a breach of fiduciary duty, which is intercausative with unjust enrichment and/or property interference. It is a type of implied trust.

In criminal law, automatism is a rarely used criminal defence. It is one of the mental condition defences that relate to the mental state of the defendant. Automatism can be seen variously as lack of voluntariness, lack of culpability (unconsciousness) or excuse. Automatism means that the defendant was not aware of his or her actions when making the particular movements that constituted the illegal act.

In criminal law, strict liability is liability for which mens rea does not have to be proven in relation to one or more elements comprising the actus reus although intention, recklessness or knowledge may be required in relation to other elements of the offense. The liability is said to be strict because defendants could be convicted even though they were genuinely ignorant of one or more factors that made their acts or omissions criminal. The defendants may therefore not be culpable in any real way, i.e. there is not even criminal negligence, the least blameworthy level of mens rea.

Self-defence is a defence permitting reasonable force to be used to defend one's self or another. This defence arises both from common law and the Criminal Law Act 1967. Self-defence is a justification defence rather than an excuse.

Duress in English law is a complete common law defence, operating in favour of those who commit crimes because they are forced or compelled to do so by the circumstances, or the threats of another. The doctrine arises not only in criminal law but also in civil law, where it is relevant to contract law and trusts law.

In English law, provocation was a mitigatory defence to murder which had taken many guises over generations many of which had been strongly disapproved and modified. In closing decades, in widely upheld form, it amounted to proving a reasonable total loss of control as a response to another's objectively provocative conduct sufficient to convert what would otherwise have been murder into manslaughter. It only applied to murder. It was abolished on 4 October 2010 by section 56(1) of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, but thereby replaced by the superseding—and more precisely worded—loss of control.

In English law, diminished responsibility is one of the partial defenses that reduce the offense from murder to manslaughter if successful. This allows the judge sentencing discretion, e.g. to impose a hospital order under section 37 of the Mental Health Act 1983 to ensure treatment rather than punishment in appropriate cases. Thus, when the actus reus of death is accompanied by an objective or constructive version of mens rea, the subjective evidence that the defendant did intend to kill or cause grievous bodily harm because of a mental incapacity will partially excuse his conduct. Under s.2(2) of the Homicide Act 1957 the burden of proof is on the defendant to the balance of probabilities. The M'Naghten Rules lack a volitional limb of "irresistible impulse"; diminished responsibility is the volitional mental condition defense in English criminal law.

In the English law of homicide, manslaughter is a less serious offence than murder, the differential being between levels of fault based on the mens rea or by reason of a partial defence. In England and Wales, a common practice is to prefer a charge of murder, with the judge or defence able to introduce manslaughter as an option. The jury then decides whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty of either murder or manslaughter. On conviction for manslaughter, sentencing is at the judge's discretion, whereas a sentence of life imprisonment is mandatory on conviction for murder. Manslaughter may be either voluntary or involuntary, depending on whether the accused has the required mens rea for murder.

In the law of England and Wales, fitness to plead is the capacity of a defendant in criminal proceedings to comprehend the course of those proceedings. The concept of fitness to plead also applies in Scots and Irish law. Its United States equivalent is competence to stand trial.

Bratty v Attorney-General for Northern Ireland [1963] AC 386, [1961] 3 All ER 523, [1961] UKHL 3 is a House of Lords decision relating to non-insane automatism. The court decided that medical evidence is needed to prove that the defendant was not aware of what they were doing, and if this is available, the burden of proof lies with the prosecution to prove that intention was present.

English criminal law concerns offences, their prevention and the consequences, in England and Wales. Criminal conduct is considered to be a wrong against the whole of a community, rather than just the private individuals affected. The state, in addition to certain international organisations, has responsibility for crime prevention, for bringing the culprits to justice, and for dealing with convicted offenders. The police, the criminal courts and prisons are all publicly funded services, though the main focus of criminal law concerns the role of the courts, how they apply criminal statutes and common law, and why some forms of behaviour are considered criminal. The fundamentals of a crime are a guilty act and a guilty mental state. The traditional view is that moral culpability requires that a defendant should have recognised or intended that they were acting wrongly, although in modern regulation a large number of offences relating to road traffic, environmental damage, financial services and corporations, create strict liability that can be proven simply by the guilty act.

The right to silence in England and Wales is the protection given to a person during criminal proceedings from adverse consequences of remaining silent. It is sometimes referred to as the privilege against self-incrimination. It is used on any occasion when it is considered the person being spoken to is under suspicion of having committed one or more criminal offences and consequently thus potentially being subject to criminal proceedings.

R v Davis [2008] UKHL 36 is a decision of the United Kingdom House of Lords which considered the permissibility of allowing witnesses to give evidence anonymously. In 2002 two men were shot and killed at a party, allegedly by the defendant, Ian Davis. He was extradited from the United States and tried at the Central Criminal Court for two counts of murder in 2004. He was convicted by the jury and appealed. The decision of the House of Lords in June 2008 led to Parliament passing the Criminal Evidence Act 2008 a month later. This legislation was later replaced by sections 86 to 97 of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009.

DPP v Camplin (1978) was an English criminal law appeal to the House of Lords in 1978. Its unanimous judgment helped to define the main limits of defence of provocation chiefly until Parliament replaced the defence with one of "loss of control" in the Coroners and Justice Act 2009. Its ratio decidendi continues to have precedent value as the new "loss of control" defence is a renaming to avoid creep of the term into scenarios for which it was never intended, above all a blurring with diminished responsibility.

Watkins v Home Office and others[2006] UKHL 17, was a United Kingdom legal case heard by the House of Lords where the Home Office made an appeal as to whether the tort of misfeasance in public office was actionable in the absence of proof of pecuniary losses or injury of a mental or physical nature. The appeal was upheld, ruling that the tort of misfeasance in public office is never actionable without proof of material damage as defined by Lord Bingham of Cornhill.

References

- ↑ Barron's Law Dictionary, p. 56 (2nd ed. 1984).

- ↑ Tapper, Collin (2010). Cross & Tapper on Evidence (11 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-19-929200-4.

- ↑ Sheldrake v DPP [2004] UKHL 43 , [2005] 1 AC 264, [2005] 1 All ER 237, [2004] 3 WLR 976(14 October 2004), House of Lords

- ↑ Barron's Law Dictionary, pp. 55-56 (2nd ed. 1984).

- ↑ Herring, J. (2004). Criminal Law: Text, Cases, and Materials. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 58–64. ISBN 0-19-876578-9.

- ↑ Jackson, Michael (2003). Criminal Law in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 962-209-558-5.

- ↑ "Bribery, Corruption and Organised Crime". Hong Kong Lawyer. May 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ R v. Acott [1997] UKHL 5 , [1997] 1 WLR 306, [1997] Crim LR 514, 161 JP 368, [1997] 1 All ER 706, [1997] 2 Cr App Rep 94(20 February 1997), House of Lords

- ↑ "Web JCLI Index".

- ↑ Bratty v Attorney General of Northern Ireland [1961] UKHL 3 , [1963] AC 386, [1961] 3 All ER 523(3 October 1961), House of Lords

- ↑ R v. Director of Public Prosecutions, Ex Parte Kebeline and Others [1999] UKHL 43 , [2000] Crim LR 486, [2000] 1 Cr App Rep 275, [1999] 3 WLR 972, [2000] 2 AC 326, [1999] 4 All ER 801(28 October 1999), House of Lords