In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, with cost per unit of output decreasing with increasing scale. At the basis of economies of scale there may be technical, statistical, organizational or related factors to the degree of market control.

Gross domestic products (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced in a specific time period, often annually. GDP (nominal) per capita does not, however, reflect differences in the cost of living and the inflation rates of the countries; therefore using a basis of GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) is arguably more useful when comparing differences in living standards between nations.

Macroeconomics is a branch of economics dealing with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole. This includes regional, national, and global economies.

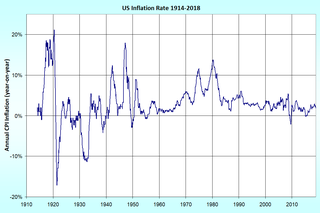

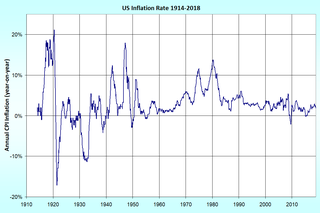

In economics, inflation is a sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation reflects a reduction in the purchasing power per unit of money – a loss of real value in the medium of exchange and unit of account within the economy. The opposite of inflation is deflation, a sustained decrease in the general price level of goods and services. The common measure of inflation is the inflation rate, the annualized percentage change in a general price index, usually the consumer price index, over time.

Economic growth is the increase in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy over time. It is conventionally measured as the percent rate of increase in real gross domestic product, or real GDP.

Growth accounting is a procedure used in economics to measure the contribution of different factors to economic growth and to indirectly compute the rate of technological progress, measured as a residual, in an economy. Growth accounting decomposes the growth rate of an economy's total output into that which is due to increases in the contributing amount of the factors used—usually the increase in the amount of capital and labor—and that which cannot be accounted for by observable changes in factor utilization. The unexplained part of growth in GDP is then taken to represent increases in productivity or a measure of broadly defined technological progress.

Capital intensity is the amount of fixed or real capital present in relation to other factors of production, especially labor. At the level of either a production process or the aggregate economy, it may be estimated by the capital to labor ratio, such as from the points along a capital/labor isoquant.

A production–possibility frontier (PPF) or production possibility curve (PPC) is a curve which shows various combinations of the amounts of two goods which can be produced within the given resources and technology/a graphical representation showing all the possible options of output for two products that can be produced using all factors of production, where the given resources are fully and efficiently utilized per unit time. A PPF illustrates several economic concepts, such as allocative efficiency, economies of scale, opportunity cost, productive efficiency, and scarcity of resources.

In economics, a production function gives the technological relation between quantities of physical inputs and quantities of output of goods. The production function is one of the key concepts of mainstream neoclassical theories, used to define marginal product and to distinguish allocative efficiency, a key focus of economics. One important purpose of the production function is to address allocative efficiency in the use of factor inputs in production and the resulting distribution of income to those factors, while abstracting away from the technological problems of achieving technical efficiency, as an engineer or professional manager might understand it.

Productivity describes various measures of the efficiency of production. Often, a productivity measure is expressed as the ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production process, i.e. output per unit of input, typically over a specific period of time. Most common example is the (aggregate) labour productivity measure, e.g., such as GDP per worker. There are many different definitions of productivity and the choice among them depends on the purpose of the productivity measurement and/or data availability. The key source of difference between various productivity measures is also usually related to how the outputs and the inputs are aggregated into scalars to obtain such a ratio-type measure of productivity.

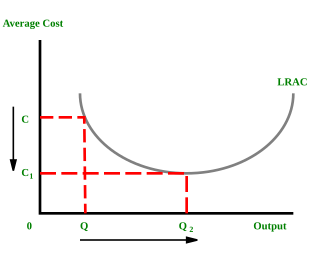

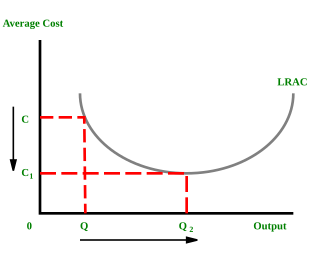

In economics, average cost or unit cost is equal to total cost (TC) divided by the number of units of a good produced :

A technical change is a term used in economics to describe a change in the amount of output produced from the same amount of inputs. A technical change is not necessarily technological as it might be organizational, or due to a change in a constraint such as regulation, input prices, or quantities of inputs.

In economics, a cost curve is a graph of the costs of production as a function of total quantity produced. In a free market economy, productively efficient firms optimize their production process by minimizing cost consistent with each possible level of production, and the result is a cost curve. profit maximizing firms use cost curves to decide output quantities. There are various types of cost curves, all related to each other, including total and average cost curves; marginal cost curves, which are equal to the differential of the total cost curves; and variable cost curves. Some are applicable to the short run, others to the long run.

The Solow residual is a number describing empirical productivity growth in an economy from year to year and decade to decade. Robert Solow, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences-winning economist, defined rising productivity as rising output with constant capital and labor input. It is a "residual" because it is the part of growth that is not accounted for by measures of capital accumulation or increased labor input. Increased physical throughput – i.e. environmental resources – is specifically excluded from the calculation; thus some portion of the residual can be ascribed to increased physical throughput. The example used is for the intracapital substitution of aluminium fixtures for steel during which the inputs do not alter. This differs in almost every other economic circumstance in which there are many other variables. The Solow Residual is procyclical and measures of it are now called the rate of growth of multifactor productivity or total factor productivity, though Solow (1957) did not use these terms.

In economics, total-factor productivity (TFP), also called multi-factor productivity, is usually measured as the ratio of aggregate output to aggregate inputs. Under some simplifications about the production technology, growth in TFP becomes the portion of growth in output not explained by growth in traditionally measured inputs of labour and capital used in production. TFP is calculated by dividing output by the weighted average of labour and capital input, with the standard weighting of 0.7 for labour and 0.3 for capital. Total factor productivity is a measure of economic efficiency and accounts for part of the differences in cross-country per-capita income. The rate of TFP growth is calculated by subtracting growth rates of labor and capital inputs from the growth rate of output.

In economics the long run is a theoretical concept in which all markets are in equilibrium, and all prices and quantities have fully adjusted and are in equilibrium. The long run contrasts with the short run, in which there are some constraints and markets are not fully in equilibrium.

Production is a process of combining various material inputs and immaterial inputs in order to make something for consumption (output). It is the act of creating an output, a good or service which has value and contributes to the utility of individuals. The area of economics that focuses on production is referred to as production theory, which in many respects is similar to the consumption theory in economics.

Unified growth theory was developed in light of the failure of endogenous growth theory to capture key empirical regularities in the growth processes and their contribution to the momentous rise in inequality across nations in the past two centuries. Unlike earlier growth theories that have focused entirely on the modern growth regime, unified growth theory captures the growth process over the entire course of human existence, highlighting the critical role of the differential timing of the transition from Malthusian stagnation to sustained economic growth in the emergence of inequality across countries and regions.

The Cambridge capital controversy, sometimes called "the capital controversy" or "the two Cambridges debate", was a dispute between proponents of two differing theoretical and mathematical positions in economics that started in the 1950s and lasted well into the 1960s. The debate concerned the nature and role of capital goods and a critique of the neoclassical vision of aggregate production and distribution. The name arises from the location of the principals involved in the controversy: the debate was largely between economists such as Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa at the University of Cambridge in England and economists such as Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.