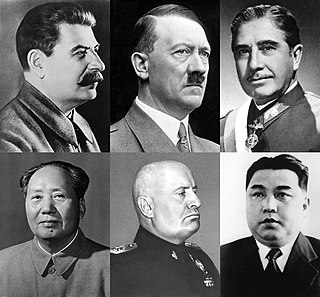

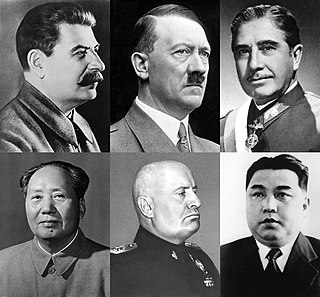

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a polity. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times of emergency. Like the term tyrant, and to a lesser degree autocrat, dictator came to be used almost exclusively as a non-titular term for oppressive rule. In modern usage the term dictator is generally used to describe a leader who holds or abuses an extraordinary amount of personal power.

Kurt Vonnegut was an American author known for his satirical and darkly humorous novels. His published work includes fourteen novels, three short-story collections, five plays, and five nonfiction works over fifty-plus years; further works have been published since his death.

Cat's Cradle is a satirical postmodern novel, with science fiction elements, by American writer Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut's fourth novel, it was first published on March 18, 1963, exploring and satirizing issues of science, technology, the purpose of religion, and the arms race, often through the use of morbid humor.

Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is a 1969 semi-autobiographic science fiction-infused anti-war novel by Kurt Vonnegut. It follows the life experiences of Billy Pilgrim, from his early years, to his time as an American soldier and chaplain's assistant during World War II, to the post-war years. Throughout the novel, Billy frequently travels back and forth through time. The protagonist deals with a temporal crisis as a result of his post-war psychological trauma. The text centers on Billy's capture by the German Army and his survival of the Allied firebombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, an experience that Vonnegut endured as an American serviceman. The work has been called an example of "unmatched moral clarity" and "one of the most enduring anti-war novels of all time".

Bluebeard, the Autobiography of Rabo Karabekian (1916–1988) is a 1987 novel by American author Kurt Vonnegut. It is told as a first-person narrative and describes the late years of fictional Abstract Expressionist painter Rabo Karabekian, who first appeared as a minor character in Vonnegut's Breakfast of Champions (1973). Circumstances of the novel bear rough resemblance to the fairy tale of Bluebeard popularized by Charles Perrault. Karabekian mentions this relationship once in the novel.

Breakfast of Champions, or Goodbye Blue Monday is a 1973 novel by the American author Kurt Vonnegut. His seventh novel, it is set predominantly in the fictional town of Midland City, Ohio, and focuses on two characters: Dwayne Hoover, a Midland resident, Pontiac dealer and affluent figure in the city, and Kilgore Trout, a widely published but mostly unknown science fiction author. Breakfast of Champions deals with themes of free will, suicide, and race relations, among others. The novel is full of drawings by the author, substituting descriptive language with depictions requiring no translation.

The Sirens of Titan is a comic science fiction novel by Kurt Vonnegut Jr., first published in 1959. His second novel, it involves issues of free will, omniscience, and the overall purpose of human history, with much of the story revolving around a Martian invasion of Earth.

Player Piano is the debut novel by American writer Kurt Vonnegut Jr., published in 1952. The novel depicts a dystopia of automation partly inspired by the author's time working at General Electric, describing the negative impact technology can have on quality of life. The story takes place in a near-future society that is almost totally mechanized, eliminating the need for human laborers. The widespread mechanization creates conflict between the wealthy upper class, the engineers and managers, who keep society running, and the lower class, whose skills and purpose in society have been replaced by machines. The book uses irony and sentimentality, which were to become hallmarks developed further in Vonnegut's later works.

Slapstick, or Lonesome No More! is a novel by American author Kurt Vonnegut. Written in 1976, it depicts Vonnegut's views of loneliness, both on an individual and social scale.

The Female Man is a feminist science fiction novel by American writer Joanna Russ. It was originally written in 1970 and first published in 1975 by Bantam Books. Russ was an ardent feminist and challenged sexist views during the 1970s with her novels, short stories, and nonfiction works. These works include We Who Are About To..., "When It Changed", and What Are We Fighting For?: Sex, Race, Class, and the Future of Feminism.

Leslie Poles Hartley was an English novelist and short story writer. Although his first fiction was published in 1924, his best-known works are the Eustace and Hilda trilogy (1944–1947) and The Go-Between (1953). The latter was made into a film in 1971, as was his 1957 novel The Hireling in 1973.

Jael or Yael is a heroine of the Bible who aids the Israelites in their war with King Jabin of the city of Hazor in Canaan by killing Sisera, the commander of Jabin's army. This episode is depicted in chapters 4 and 5 of the Book of Judges. According to that account, after Sisera's defeat by the Israelite king Barak in the Battle of Mount Tabor, he seeks refuge in the tent of Jael, who kills him by driving a tent peg through his skull near the great tree in Zaanaim near Kedesh.

Subterranean fiction is a subgenre of speculative fiction, science fiction, or fantasy which focuses on fictional underground settings, sometimes at the center of the Earth or otherwise deep below the surface. The genre is based on, and has in turn influenced, the Hollow Earth theory. The earliest works in the genre were Enlightenment-era philosophical or allegorical works, in which the underground setting was often largely incidental. In the late 19th century, however, more pseudoscientific or proto-science-fictional motifs gained prevalence. Common themes have included a depiction of the underground world as more primitive than the surface, either culturally, technologically or biologically, or in some combination thereof. The former cases usually see the setting used as a venue for sword-and-sorcery fiction, while the latter often features cryptids or creatures extinct on the surface, such as dinosaurs or archaic humans. A less frequent theme has the underground world much more technologically advanced than the surface one, typically either as the refugium of a lost civilization, or as a secret base for space aliens.

The Secret People (1935) is a science fiction novel by English writer John Wyndham. It is set in 1964, and features a British couple who find themselves held captive by an ancient race of pygmies dwelling beneath the Sahara desert. The novel was written under Wyndham's early pen name, John Beynon.

Les Indes noires is a novel by the French writer Jules Verne, serialized in Le Temps in March and April 1877 and published immediately afterward by Pierre-Jules Hetzel. The first UK edition was published in October 1877 by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington as The Child of the Cavern, or Strange Doings Underground. Other English titles for the novel include Black Diamonds and The Underground City.

El Señor Presidente is a 1946 novel written in Spanish by Nobel Prize-winning Guatemalan writer and diplomat Miguel Ángel Asturias (1899–1974). A landmark text in Latin American literature, El Señor Presidente explores the nature of political dictatorship and its effects on society. Asturias makes early use of a literary technique now known as magic realism. One of the most notable works of the dictator novel genre, El Señor Presidente developed from an earlier Asturias short story, written to protest social injustice in the aftermath of a devastating earthquake in the author's home town.

A dystopia, also called a cacotopia or anti-utopia, is a community or society that is extremely bad or frightening. It is often treated as an antonym of utopia, a term that was coined by Sir Thomas More and figures as the title of his best known work, published in 1516, which created a blueprint for an ideal society with minimal crime, violence, and poverty. The relationship between utopia and dystopia is in actuality, not one of simple opposition, as many dystopias claim to be utopias and vice versa.

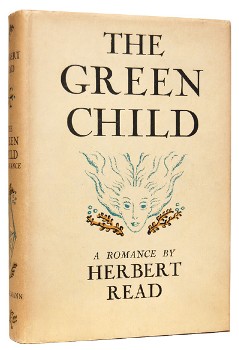

The Green Child is the only completed novel by the English anarchist poet and critic Herbert Read. Written in 1934 and first published by Heinemann in 1935, the story is based on the 12th-century legend of two green children who mysteriously appeared in the English village of Woolpit, speaking an apparently unknown language. Read described the legend in his English Prose Style, published in 1931, as "the norm to which all types of fantasy should conform".

The Name of Action is Graham Greene's second novel, published in 1930. The book was badly received by critics, and suffered poor sales. Greene later repudiated the book and it has remained out of print ever since.

Hidden World is a satiric science fiction novel by American writer Stanton A. Coblentz. It was originally published as a magazine serial in Wonder Stories as In Caverns Below. It was first published in book form in 1957 by Avalon Books.