Related Research Articles

Sexual attraction is attraction on the basis of sexual desire or the quality of arousing such interest. Sexual attractiveness or sex appeal is an individual's ability to attract other people sexually, and is a factor in sexual selection or mate choice. The attraction can be to the physical or other qualities or traits of a person, or to such qualities in the context where they appear. The attraction may be to a person's aesthetics, movements, voice, or smell, among other things. The attraction may be enhanced by a person's adornments, clothing, perfume or hair style. It can be influenced by individual genetic, psychological, or cultural factors, or to other, more amorphous qualities. Sexual attraction is also a response to another person that depends on a combination of the person possessing the traits and on the criteria of the person who is attracted.

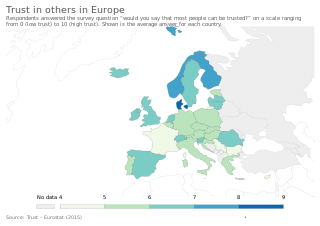

Trust is the willingness of one party to become vulnerable to another party on the presumption that the trustee will act in ways that benefit the trustor. In addition, the trustor does not have control over the actions of the trustee. Scholars distinguish between generalized trust, which is the extension of trust to a relatively large circle of unfamiliar others, and particularized trust, which is contingent on a specific situation or a specific relationship.

The physical attractiveness stereotype is the tendency to assume that people who are physically attractive, based on social beauty standards, also possess other desirable personality traits. Research has shown that those who are physically attractive are viewed as more intelligent, competent, and socially desirable. The target benefits from what has been coined as pretty privilege, namely social, economic, and political advantages or benefits. Physical attractiveness can have a significant effect on how people are judged in terms of employment or social opportunities, friendship, sexual behavior, and marriage.

Interpersonal attraction, as a part of social psychology, is the study of the attraction between people which leads to the development of platonic or romantic relationships. It is distinct from perceptions such as physical attractiveness, and involves views of what is and what is not considered beautiful or attractive.

Physical attractiveness is the degree to which a person's physical features are considered aesthetically pleasing or beautiful. The term often implies sexual attractiveness or desirability, but can also be distinct from either. There are many factors which influence one person's attraction to another, with physical aspects being one of them. Physical attraction itself includes universal perceptions common to all human cultures such as facial symmetry, sociocultural dependent attributes and personal preferences unique to a particular individual.

The dictator game is a popular experimental instrument in social psychology and economics, a derivative of the ultimatum game. The term "game" is a misnomer because it captures a decision by a single player: to send money to another or not. Thus, the dictator has the most power and holds the preferred position in this “game.” Although the “dictator” has the most power and presents a take it or leave it offer, the game has mixed results based on different behavioral attributes. The results – where most "dictators" choose to send money – evidence the role of fairness and norms in economic behavior, and undermine the assumption of narrow self-interest when given the opportunity to maximise one's own profits.

Facial symmetry is one specific measure of bodily symmetry. Along with traits such as averageness and youthfulness it influences judgments of aesthetic traits of physical attractiveness and beauty. For instance, in mate selection, people have been shown to have a preference for symmetry.

Fluctuating asymmetry (FA), is a form of biological asymmetry, along with anti-symmetry and direction asymmetry. Fluctuating asymmetry refers to small, random deviations away from perfect bilateral symmetry. This deviation from perfection is thought to reflect the genetic and environmental pressures experienced throughout development, with greater pressures resulting in higher levels of asymmetry. Examples of FA in the human body include unequal sizes (asymmetry) of bilateral features in the face and body, such as left and right eyes, ears, wrists, breasts, testicles, and thighs.

David Ian Perrett FBA FRSE is a professor of psychology at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, where he leads the Perception Lab. The main focus in his team's research is on face perception, including facial cues to health, effects of physiological conditions on facial appearance, and facial preferences in social settings such as trust games and mate choice. He has published over 400 peer-reviewed articles, many of which appearing in leading scientific journals such as the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B—Biological Sciences, Psychological Science, and Nature.

Benedict Jones is a research psychologist and lecturer at the University of Glasgow who studies the biological and social factors underlying face perception and preferences. He received his PhD from the University of St Andrews in 2005, where he studied with David Perrett.

Mate choice is one of the primary mechanisms under which evolution can occur. It is characterized by a "selective response by animals to particular stimuli" which can be observed as behavior. In other words, before an animal engages with a potential mate, they first evaluate various aspects of that mate which are indicative of quality—such as the resources or phenotypes they have—and evaluate whether or not those particular trait(s) are somehow beneficial to them. The evaluation will then incur a response of some sort.

The hyperpersonal model is a model of interpersonal communication that suggests computer-mediated communication (CMC) can become hyperpersonal because it "exceeds [face-to-face] interaction", thus affording message senders a host of communicative advantages over traditional face-to-face (FtF) interaction. The hyperpersonal model demonstrates how individuals communicate uniquely, while representing themselves to others, how others interpret them, and how the interactions create a reciprocal spiral of FtF communication. Compared to ordinary FtF situations, a hyperpersonal message sender has a greater ability to strategically develop and edit self-presentation, enabling a selective and optimized presentation of one's self to others.

Sexual selection in humans concerns the concept of sexual selection, introduced by Charles Darwin as an element of his theory of natural selection, as it affects humans. Sexual selection is a biological way one sex chooses a mate for the best reproductive success. Most compete with others of the same sex for the best mate to contribute their genome for future generations. This has shaped human evolution for many years, but reasons why humans choose their mates are not fully understood. Sexual selection is quite different in non-human animals than humans as they feel more of the evolutionary pressures to reproduce and can easily reject a mate. The role of sexual selection in human evolution has not been firmly established although neoteny has been cited as being caused by human sexual selection. It has been suggested that sexual selection played a part in the evolution of the anatomically modern human brain, i.e. the structures responsible for social intelligence underwent positive selection as a sexual ornamentation to be used in courtship rather than for survival itself, and that it has developed in ways outlined by Ronald Fisher in the Fisherian runaway model. Fisher also stated that the development of sexual selection was "more favourable" in humans.

Mnemic neglect is a term used in social psychology to describe a pattern of selective forgetting in which certain autobiographical memories tend to be recalled more easily if they are consistent with positive self-concept. The mnemic neglect model stipulates that memory is self-protective if the information is negative, self-referent, and concerns central traits.

Odour is sensory stimulation of the olfactory membrane of the nose by a group of molecules. Certain body odours are connected to human sexual attraction. Humans can make use of body odour subconsciously to identify whether a potential mate will pass on favourable traits to their offspring. Body odour may provide significant cues about the genetic quality, health and reproductive success of a potential mate.

Nonverbal influence is the act of affecting or inspiring change in others' behaviors and attitudes by way of tone of voice or body language and other cues like facial expression. This act of getting others to embrace or resist new attitudes can be achieved with or without the use of spoken language. It is a subtopic of nonverbal communication. Many individuals instinctively associate persuasion with verbal messages. Nonverbal influence emphasizes the persuasive power and influence of nonverbal communication. Nonverbal influence includes appeals to attraction, similarity and intimacy.

Relationship maintenance refers to a variety of behaviors exhibited by relational partners in an effort to maintain that relationship. Scholars define relational maintenance in four different ways: to keep a relationship in existence, to keep a relationship in a specified state or condition, to keep a relationship in a satisfactory condition, and to keep a relationship in repair.

Mate value is derived from Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and sexual selection, as well as the social exchange theory of relationships. Mate value is defined as the sum of traits that are perceived as desirable, representing genetic quality and/or fitness (biology), an indication of a potential mate's reproductive success. Based on mate desirability and mate preference, mate value underpins mate selection and the formation of romantic relationships.

Female intrasexual competition is competition between women over a potential mate. Such competition might include self-promotion, derogation of other women, and direct and indirect aggression toward other women. Factors that influence female intrasexual competition include the genetic quality of available mates, hormone levels, and interpersonal dynamics.

In humans, males and females differ in their strategies to acquire mates and focus on certain qualities. There are two main categories of strategies that both sexes utilize: short-term and long-term. Human mate choice, an aspect of sexual selection in humans, depends on a variety of factors, such as ecology, demography, access to resources, rank/social standing, genes, and parasite stress.

References

- 1 2 3 DeBruine, Lisa M. (2002). "Facial Resemblance Enhances Trust". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 269 (1498): 1307–1312. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2034. PMC 1691034 . PMID 12079651.

- 1 2 3 DeBruine, L. M. (2005). "Trustworthy but Not Lust-worthy: Context-specific Effects of Facial Resemblance". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1566): 919–922. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3003. PMC 1564091 . PMID 16024346.