In music theory, the tritone is defined as a musical interval spanning three adjacent whole tones. For instance, the interval from F up to the B above it is a tritone as it can be decomposed into the three adjacent whole tones F–G, G–A, and A–B.

Articles related to music include:

A fourth is a musical interval encompassing four staff positions in the music notation of Western culture, and a perfect fourth is the fourth spanning five semitones. For example, the ascending interval from C to the next F is a perfect fourth, because the note F is the fifth semitone above C, and there are four staff positions between C and F. Diminished and augmented fourths span the same number of staff positions, but consist of a different number of semitones.

In music theory, a perfect fifth is the musical interval corresponding to a pair of pitches with a frequency ratio of 3:2, or very nearly so.

In the music theory of harmony, the root is a specific note that names and typifies a given chord. Chords are often spoken about in terms of their root, their quality, and their extensions. When a chord is named without reference to quality, it is assumed to be major—for example, a "C chord" refers to a C major triad, containing the notes C, E, and G. In a given harmonic context, the root of a chord need not be in the bass position, as chords may be inverted while retaining the same name, and therefore the same root.

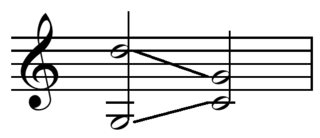

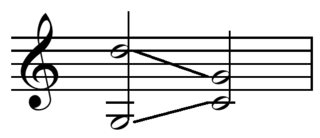

In music theory, a dominant seventh chord, or major minor seventh chord, is a seventh chord, composed of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. Thus it is a major triad together with a minor seventh, denoted by the letter name of the chord root and a superscript "7". In most cases, dominant seventh chord are built on the fifth degree of the major scale. An example is the dominant seventh chord built on G, written as G7, having pitches G–B–D–F:

Jehan le Taintenier or Jean Teinturier was a Renaissance music theorist and composer from the Low Countries. Up to his time, he is perhaps the most significant European writer on music since Guido of Arezzo.

The root position of a chord is the voicing of a triad, seventh chord, or ninth chord in which the root of the chord is the bass note and the other chord factors are above it. In the root position, uninverted, of a C-major triad, the bass is C — the root of the triad — with the third and the fifth stacked above it, forming the intervals of a third and a fifth above the root of C, respectively.

In music, a guitar chord is a set of notes played on a guitar. A chord's notes are often played simultaneously, but they can be played sequentially in an arpeggio. The implementation of guitar chords depends on the guitar tuning. Most guitars used in popular music have six strings with the "standard" tuning of the Spanish classical guitar, namely E–A–D–G–B–E' ; in standard tuning, the intervals present among adjacent strings are perfect fourths except for the major third (G,B). Standard tuning requires four chord-shapes for the major triads.

In music, consecutive fifths or parallel fifths are progressions in which the interval of a perfect fifth is followed by a different perfect fifth between the same two musical parts : for example, from C to D in one part along with G to A in a higher part. Octave displacement is irrelevant to this aspect of musical grammar; for example, a parallel twelfth is equivalent to a parallel fifth.

The omnibus progression in music is a chord progression characterized by chromatic lines moving in opposite directions. The progression has its origins in the various Baroque harmonizations of the descending chromatic fourth in the bass ostinato pattern of passacaglia, known as the "lament bass". However, in its fullest form the omnibus progression involves a descent in the bass which traverses a whole octave and includes every note of the chromatic scale. It may also include one or more chromatic ascending tetrachords in the soprano, tenor and alto.

Fauxbourdon – French for false drone – is a technique of musical harmonisation used in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, particularly by composers of the Burgundian School. Guillaume Dufay was a prominent practitioner of the form, and may have been its inventor. The homophony and mostly parallel harmony allows the text of the mostly liturgical lyrics to be understood clearly.

A descant, discant, or discantus is any of several different things in music, depending on the period in question; etymologically, the word means a voice (cantus) above or removed from others. The Harvard Dictionary of Music states:

Anglicized form of L. discantus and a variant of discant. Throughout the Middle Ages the term was used indiscriminately with other terms, such as descant. In the 17th century it took on special connotations in instrumental practice.

In music, alternate bass is a performance technique on many instruments where the bass alternates between two notes, most often the root and the fifth of a triad or chord. The perfect fifth is often, but not always, played below the root, transposed down an octave creating a fourth interval. The alternation between the root note and the fifth scale degree below it creates the characteristic sound of the alternate bass.

The second inversion of a chord is the voicing of a triad, seventh chord, or ninth chord in which the fifth of the chord is the bass note. In this inversion, the bass note and the root of the chord are a fourth apart which traditionally qualifies as a dissonance. There is therefore a tendency for movement and resolution. In notation form, it is referred to with a c following the chord position. In figured bass, a second-inversion triad is a 6

4 chord, while a second-inversion seventh chord is a 4

3 chord.

Inversions are not restricted to the same number of tones as the original chord, nor to any fixed order of tones except with regard to the interval between the root, or its octave, and the bass note, hence, great variety results.

The first inversion of a chord is the voicing of a triad, seventh chord, or ninth chord in which the third of the chord is the bass note and the root a sixth above it. In the first inversion of a C-major triad, the bass is E — the third of the triad — with the fifth and the root stacked above it, forming the intervals of a minor third and a minor sixth above the inverted bass of E, respectively.

Chuck Wayne was an American jazz guitarist. He came to prominence in the 1940s, and was among the earliest jazz guitarists to play in the bebop style. Wayne was a member of Woody Herman's First Herd, the first guitarist in the George Shearing quintet, and Tony Bennett's music director and accompanist. He developed a systematic method for playing jazz guitar.

The Stradella Bass System is a buttonboard layout equipped on the bass side of many accordions, which uses columns of buttons arranged in a circle of fifths; this places the principal major chords of a key in three adjacent columns.

The term "four-part harmony" refers to music written for four voices, or for some other musical medium—four musical instruments or a single keyboard instrument, for example—for which the various musical parts can give a different note for each chord of the music.

In music, a factor or chord factor is a member or component of a chord. These are named root, third, fifth, sixth, seventh, ninth, eleventh, thirteenth, and so on, for their generic interval above the root. In harmony, the consonance and dissonance of a chord factor and a nonchord tone are distinguished, respectively.