Related Research Articles

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others extend the definition to include substances like aerosols and gels. The term colloidal suspension refers unambiguously to the overall mixture. A colloid has a dispersed phase and a continuous phase. The dispersed phase particles have a diameter of approximately 1 nanometre to 1 micrometre.

An emulsion is a mixture of two or more liquids that are normally immiscible owing to liquid-liquid phase separation. Emulsions are part of a more general class of two-phase systems of matter called colloids. Although the terms colloid and emulsion are sometimes used interchangeably, emulsion should be used when both phases, dispersed and continuous, are liquids. In an emulsion, one liquid is dispersed in the other. Examples of emulsions include vinaigrettes, homogenized milk, liquid biomolecular condensates, and some cutting fluids for metal working.

Rheology is the study of the flow of matter, primarily in a liquid or gas state, but also as "soft solids" or solids under conditions in which they respond with plastic flow rather than deforming elastically in response to an applied force. Rheology is a branch of physics, and it is the science that deals with the deformation and flow of materials, both solids and liquids.

An aerosol is a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be natural or anthropogenic. Examples of natural aerosols are fog or mist, dust, forest exudates, and geyser steam. Examples of anthropogenic aerosols are particulate air pollutants and smoke. The liquid or solid particles have diameters typically less than 1 μm; larger particles with a significant settling speed make the mixture a suspension, but the distinction is not clear-cut. In general conversation, aerosol usually refers to an aerosol spray that delivers a consumer product from a can or similar container. Other technological applications of aerosols include dispersal of pesticides, medical treatment of respiratory illnesses, and combustion technology. When a person inhales the contents of a vape pen or e-cigarette, they suck an anthropogenic aerosol into their lungs.

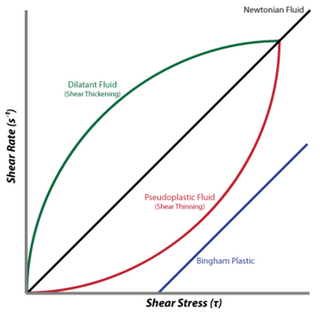

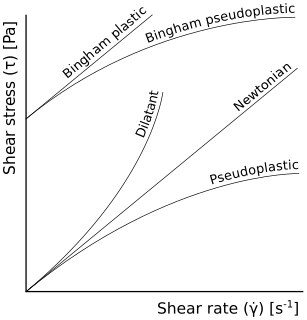

A non-Newtonian fluid is a fluid that does not follow Newton's law of viscosity, i.e., constant viscosity independent of stress. In non-Newtonian fluids, viscosity can change when under force to either more liquid or more solid. Ketchup, for example, becomes runnier when shaken and is thus a non-Newtonian fluid. Many salt solutions and molten polymers are non-Newtonian fluids, as are many commonly found substances such as custard, toothpaste, starch suspensions, corn starch, paint, blood, melted butter, and shampoo.

In chemistry, a suspension is a heterogeneous mixture of a fluid that contains solid particles sufficiently large for sedimentation. The particles may be visible to the naked eye, usually must be larger than one micrometer, and will eventually settle, although the mixture is only classified as a suspension when and while the particles have not settled out.

Hemorheology, also spelled haemorheology, or blood rheology, is the study of flow properties of blood and its elements of plasma and cells. Proper tissue perfusion can occur only when blood's rheological properties are within certain levels. Alterations of these properties play significant roles in disease processes. Blood viscosity is determined by plasma viscosity, hematocrit and mechanical properties of red blood cells. Red blood cells have unique mechanical behavior, which can be discussed under the terms erythrocyte deformability and erythrocyte aggregation. Because of that, blood behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid. As such, the viscosity of blood varies with shear rate. Blood becomes less viscous at high shear rates like those experienced with increased flow such as during exercise or in peak-systole. Therefore, blood is a shear-thinning fluid. Contrarily, blood viscosity increases when shear rate goes down with increased vessel diameters or with low flow, such as downstream from an obstruction or in diastole. Blood viscosity also increases with increases in red cell aggregability.

A magnetorheological fluid is a type of smart fluid in a carrier fluid, usually a type of oil. When subjected to a magnetic field, the fluid greatly increases its apparent viscosity, to the point of becoming a viscoelastic solid. Importantly, the yield stress of the fluid when in its active ("on") state can be controlled very accurately by varying the magnetic field intensity. The upshot is that the fluid's ability to transmit force can be controlled with an electromagnet, which gives rise to its many possible control-based applications. Extensive discussions of the physics and applications of MR fluids can be found in a recent book.

Thixotropy is a time-dependent shear thinning property. Certain gels or fluids that are thick or viscous under static conditions will flow over time when shaken, agitated, shear-stressed, or otherwise stressed. They then take a fixed time to return to a more viscous state. Some non-Newtonian pseudoplastic fluids show a time-dependent change in viscosity; the longer the fluid undergoes shear stress, the lower its viscosity. A thixotropic fluid is a fluid which takes a finite time to attain equilibrium viscosity when introduced to a steep change in shear rate. Some thixotropic fluids return to a gel state almost instantly, such as ketchup, and are called pseudoplastic fluids. Others such as yogurt take much longer and can become nearly solid. Many gels and colloids are thixotropic materials, exhibiting a stable form at rest but becoming fluid when agitated. Thixotropy arises because particles or structured solutes require time to organize. An overview of thixotropy has been provided by Mewis and Wagner.

A dilatant material is one in which viscosity increases with the rate of shear strain. Such a shear thickening fluid, also known by the initialism STF, is an example of a non-Newtonian fluid. This behaviour is usually not observed in pure materials, but can occur in suspensions.

Electrorheological (ER) fluids are suspensions of extremely fine non-conducting but electrically active particles in an electrically insulating fluid. The apparent viscosity of these fluids changes reversibly by an order of up to 100,000 in response to an electric field. For example, a typical ER fluid can go from the consistency of a liquid to that of a gel, and back, with response times on the order of milliseconds. The effect is sometimes called the Winslow effect after its discoverer, the American inventor Willis Winslow, who obtained a US patent on the effect in 1947 and wrote an article published in 1949.

Rheometry generically refers to the experimental techniques used to determine the rheological properties of materials, that is the qualitative and quantitative relationships between stresses and strains and their derivatives. The techniques used are experimental. Rheometry investigates materials in relatively simple flows like steady shear flow, small amplitude oscillatory shear, and extensional flow.

A thickening agent or thickener is a substance which can increase the viscosity of a liquid without substantially changing its other properties. Edible thickeners are commonly used to thicken sauces, soups, and puddings without altering their taste; thickeners are also used in paints, inks, explosives, and cosmetics.

In rheology, shear thinning is the non-Newtonian behavior of fluids whose viscosity decreases under shear strain. It is sometimes considered synonymous for pseudoplastic behaviour, and is usually defined as excluding time-dependent effects, such as thixotropy.

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles (sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and/or the movement of the fluid in which the sediment is entrained. Sediment transport occurs in natural systems where the particles are clastic rocks, mud, or clay; the fluid is air, water, or ice; and the force of gravity acts to move the particles along the sloping surface on which they are resting. Sediment transport due to fluid motion occurs in rivers, oceans, lakes, seas, and other bodies of water due to currents and tides. Transport is also caused by glaciers as they flow, and on terrestrial surfaces under the influence of wind. Sediment transport due only to gravity can occur on sloping surfaces in general, including hillslopes, scarps, cliffs, and the continental shelf—continental slope boundary.

Sedimentation potential occurs when dispersed particles move under the influence of either gravity or centrifugation in a medium. This motion disrupts the equilibrium symmetry of the particle's double layer. While the particle moves, the ions in the electric double layer lag behind due to the liquid flow. This causes a slight displacement between the surface charge and the electric charge of the diffuse layer. As a result, the moving particle creates a dipole moment. The sum of all of the dipoles generates an electric field which is called sedimentation potential. It can be measured with an open electrical circuit, which is also called sedimentation current.

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

A nanofluid is a fluid containing nanometer-sized particles, called nanoparticles. These fluids are engineered colloidal suspensions of nanoparticles in a base fluid. The nanoparticles used in nanofluids are typically made of metals, oxides, carbides, or carbon nanotubes. Common base fluids include water, ethylene glycol and oil.

Bagnold's fluid refers to a suspension of neutrally buoyant particles in a Newtonian fluid such as water or air. The term is named after Ralph Alger Bagnold, who placed such a suspension in an annular coaxial cylindrical rheometer in order to investigate the effects of grain interaction in the suspension.

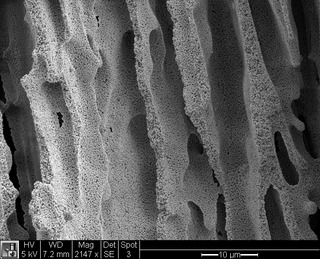

Freeze-casting, also frequently referred to as ice-templating, or freeze alignment, is a technique that exploits the highly anisotropic solidification behavior of a solvent in a well-dispersed slurry to controllably template a directionally porous ceramic. By subjecting an aqueous slurry to a directional temperature gradient, ice crystals will nucleate on one side of the slurry and grow along the temperature gradient. The ice crystals will redistribute the suspended ceramic particles as they grow within the slurry, effectively templating the ceramic.

References

- ↑ Farris, Richard J (1968). "Prediction of the Viscosity of Multimodal Suspensions from Unimodal Viscosity Data". Transactions of the Society of Rheology. 12 (2): 281–301. Bibcode:1968JRheo..12..281F. doi:10.1122/1.549109. S2CID 121137261.

- ↑ Del Gaudio, P; Ventura, G; Taddeucci, J (2013). "The effect of particle size on the rheology of liquid-solid mixtures with application to lava flows : Results from analogue experiments". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 14 (8): 2661–2669. Bibcode:2013GGG....14.2661D. doi:10.1002/ggge.20172.