Related Research Articles

The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico - particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, city-state of the Mexica or Tenochca, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although, the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era, as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821). The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early 19th century.

Maximilian I was an Austrian archduke who became emperor of the Second Mexican Empire from 10 April 1864 until his execution by the Mexican Republic on 19 June 1867.

The Nahuas are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, and the Toltecs are often thought to have been as well, though in the pre-Columbian period Nahuas were subdivided into many groups that did not necessarily share a common identity.

Tlacaelel I was the principal architect of the Aztec Triple Alliance and hence the Mexica (Aztec) empire. He was the son of Emperor Huitzilihuitl and Queen Cacamacihuatl, nephew of Emperor Itzcoatl, father of poet Macuilxochitzin, and brother of Emperors Chimalpopoca and Moctezuma I.

Chimalpopoca or Chīmalpopōcatzin (1397–1427) was the third Emperor of Tenochtitlan (1417–1427).

Tlatoani is the Classical Nahuatl term for the ruler of an āltepētl, a pre-Hispanic state. It is the noun form of the verb "tlahtoa" meaning "speak, command, rule". As a result, it has been variously translated in English as "king", "ruler", or "speaker" in the political sense. Above a tlahtoani is the Huey Tlahtoani, sometimes translated as "Great Speaker", though more usually as "Emperor". A cihuatlatoani is a female ruler, or queen regnant.

The Aztec Empire or the Triple Alliance was an alliance of three Nahua city-states: Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan. These three city-states ruled that area in and around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until the combined forces of the Spanish conquistadores and their native allies who ruled under Hernán Cortés defeated them in 1521.

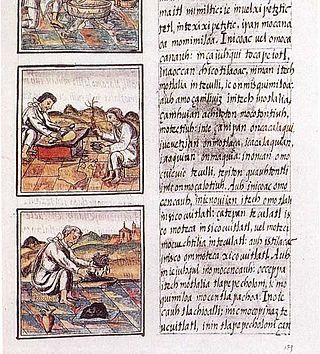

The Florentine Codex is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Sahagún originally titled it: La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España. After a translation mistake, it was given the name Historia general de las Cosas de Nueva España. The best-preserved manuscript is commonly referred to as the Florentine Codex, as the codex is held in the Laurentian Library of Florence, Italy.

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, also known as the Conquest of Mexico, the Spanish-Aztec War (1519–1521), or the Conquest of Tenochtitlan was one of the primary events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. There are multiple 16th-century narratives of the events by Spanish conquistadors, their indigenous allies, and the defeated Aztecs. It was not solely a small contingent of Spaniards defeating the Aztec Empire but a coalition of Spanish invaders with tributaries to the Aztecs, and most especially the Aztecs' indigenous enemies and rivals. They combined forces to defeat the Mexica of Tenochtitlan over a two-year period. For the Spanish, Mexico was part of a project of Spanish colonization of the New World after 25 years of permanent Spanish settlement and further exploration in the Caribbean.

The traditions of indigenous Mesoamerican literature extend back to the oldest-attested forms of early writing in the Mesoamerican region, which date from around the mid-1st millennium BCE. Many of the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica are known to have been literate societies, who produced a number of Mesoamerican writing systems of varying degrees of complexity and completeness. Mesoamerican writing systems arose independently from other writing systems in the world, and their development represents one of the very few such origins in the history of writing.

Huehue Zaca or Çaca, also Zacatzin, was a 15th-century Aztec noble, prince and a warrior who served as tlacateccatl under the ruler Moctezuma I, his brother. The name of Zaca is probably derived from Nahuatl zacatl, meaning "grass"; -tzin is an honorific or reverential suffix. Huehue is Nahuatl for "the elder", literally "old man".

Antonio Valeriano was a colonial Mexican, Nahua scholar and politician. He was a collaborator with fray Bernardino de Sahagún in the creation of the twelve-volume General History of the Things of New Spain, the Florentine Codex, He served as judge-governor of both his home, Azcapotzalco, and of Tenochtitlan, in Spanish colonial New Spain.

New Philology generally refers to a branch of Mexican ethnohistory and philology that uses colonial-era native language texts written by Indians to construct history from the indigenous point of view. The name New Philology was coined by James Lockhart to describe work that he and his doctoral students and scholarly collaborators in history, anthropology, and linguistics had pursued since the mid-1970s. Lockhart published a great many essays elaborating on the concept and content of the New Philology and Matthew Restall published a description of it in the Latin American Research Review.

James Lockhart was a U.S. historian of colonial Spanish America, especially the Nahua people and Nahuatl language.

Antonio del Rincón was a Jesuit priest and grammarian, who wrote one of the earliest grammars of the Nahuatl language.

Nahuatl, Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about 1.7 million Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller populations in the United States.

Codex Chimalpopoca or Códice Chimalpopoca is a postconquest cartographic Aztec codex which is officially listed as being in the collection of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia located in Mexico City under "Collección Antiguo no. 159". It is best known for its stories of the hero-god Quetzalcoatl. The current whereabouts of the codex are unknown. It appears to have been lost in the mid-twentieth century. Study of the codex is therefore necessarily provided only through copies and photographs. The codex consists of three parts, two of which are more important, one that regards the pre-Hispanic history of Central Mexico, the Anales de Cuauhtitlan and the other that regards the study of Aztec cosmology, the Leyenda de los Soles.

The Conservative Party was one of two major factions in Mexican political thought that emerged in the years after independence, the other being the Liberals.

The history of the Nahuatl, Aztec or Mexicano language can be traced back to the time when Teotihuacan flourished. From the 4th century AD to the present, the journey and development of the language and its dialect varieties have gone through a large number of periods and processes, the language being used by various peoples, civilizations and states throughout the history of the cultural area of Mesoamerica.

References

- ↑ McAllen, M.M. (8 January 2014). Maximilian and Carlota: Europe's Last Empire in Mexico. Trinity University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9781595341853.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. pp. 89–90.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 105.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 94.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 94.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 95.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. pp. 95–96.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 105.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 98.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. pp. 98–99.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 97.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 98.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 102.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 103.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. p. 103.

- ↑ McDonough, Kelly S. (2014). The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. University of Arizona Press. pp. 104–105.